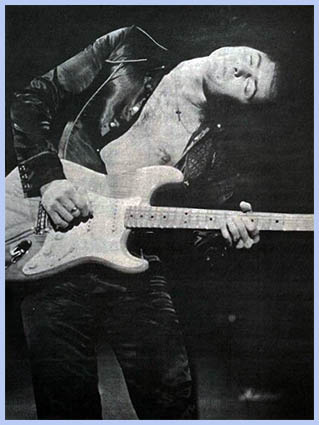

|

Ritchie Blackmore Blackmore Swings The Axe  Ritchie Blackmore harbours no love for rock 'n' roll journalists. As far as he's concerned, most of them fall into two unflattering categories, those that are either "embittered people because they're not up there" on the stage, and those that are "bored and being paid to do a job."

Ritchie Blackmore harbours no love for rock 'n' roll journalists. As far as he's concerned, most of them fall into two unflattering categories, those that are either "embittered people because they're not up there" on the stage, and those that are "bored and being paid to do a job."The tension that's developed between musician and writer has led to some very distorted portraits of Mr. Blackmore, and over the years, the moody man in black has done little, if anything, to correct or cosmeticise the image that's been drawn of him in various rock journals. I myself have put some faith in that bad boy persona. The first time I went out on the road with Purple a few years ago, there were two other writers present, and both were frantic to interview Ritchie. Believing, at the time, that meeting Blackmore alone in a hotel room was something akin to journalistic masochism, I respectfully avoided the competition for Ritchie's time, and concentrated instead in developing a rapport with the other musicians of Purple. The end result, after three days on the road, was that I hardly spoke a word to Ritchie, except for a polite hello, and vice versa. What's more, I only saw the man about four times in those three days, and twice it was when he was playing to an audience. As you might guess then, I was quite surprised recently when Ritchie actually remembered meeting me, when we again confronted each other for the sake of SOUNDS. "I wouldn't like to be a critic," Ritchie still insists, "in a way that it must be very boring. I'd hate to have to go and see bands, especially loud bands." As a recent victim of decibel backlash, I could hardly muster a defence of my profession. On top of that, the man did have some legitimate complaints about the recent roasting Deep Purple received in the British press. "I did not like the criticism of Purple," Ritchie flatly states. "I thought it was very unjust. But I thought it was typical of the English press, and they'll do the same to us, probably, when we get there. It's so obvious. "I saw a few reviews. There was a lot of people saying 'Do you want to see the reviews?' and I said 'No, not particularly. I don't want to revel in their kind of mishaps.' No band's that bad. "We do a lot of interviews for SOUNDS, who don't seem to be one-sided. They just seem to be interested in interviewing the band, and projecting music." Staff, you may now take your collective bows. "But the other newspapers seem to be really into their little clique, and they're bored, and they're old, and they're fed up with the whole business, and they go around slaggin' everybody. If they don't like them, they shouldn't say anything. The British rock press may have their chance to put up or shut up later this year, after Rainbow completes a mammoth American summer tour. "They want us to do all these big gigs in England, Empire Pool and all this shit, but we don't want to go in like a big band. We want to go in like medium, and do a few small-type places. I'd like to do a tour of England, whereas a lot of people just want us to do London. I'd rather do about ten gigs, top to bottom." Before Rainbow can come home though, they've got to finish their exhausting forty-odd city American tour. Rainbow is headlining a good majority of their gigs, but they may do some special guest support shows in the big stadiums. Some support gigs with Jethro Tull, one of Ritchie's current favourite bands, have been blown out for reasons unknown, and another support situation with Alice Cooper disolved when Alice came down with hepititis. And some other unmentionable bands missed the chance to be blown away by Rainbow when they refused the band the permission to use their rainbow onstage. As it stands now, Rainbow are doing mainly the small theatre venues, like New York's Beacon Theatre.  "I'm very pleased with the way things are going," says Ritchie as a trace of a smile crosses his face. "I've never had so much applause. We go up to the dressing room and stay there for five or ten minutes, and we'd hear a thumping, elephants stampeding, and 'Oh well, better do an encore' and that's really good. Compared with what it used to be."

"I'm very pleased with the way things are going," says Ritchie as a trace of a smile crosses his face. "I've never had so much applause. We go up to the dressing room and stay there for five or ten minutes, and we'd hear a thumping, elephants stampeding, and 'Oh well, better do an encore' and that's really good. Compared with what it used to be.""It's an adrenalin thing," is Ritchie's explanation of the fanaticism he inspires in his audiences. "If you go on and you're shy of the audience and you don't have any energy, they're gonna sit. But if you get across to them, it's like lightning hitting them. "I have to try more. I can't hide behind the rest of them," he explains, meaning the other members of Rainbow. "I can push, and at the moment, everybody's like nice guys, so we all kind of get on very well together. There's none of this back-stage animosity, or kind of egotistical things, which tend to come into a band after two or three years. "So at the moment, everybody's good friends and trying their best. But sometimes when you're in a band, and playing that long, you go out of your way to play badly, or to upset the other guy, so he has a hard time. "I used to do that with Purple sometimes. There was so much bilge going on onstage, sometimes I got disgusted with it, and I used to walk off because I didn't want to have any part of what was going down at that particular time. I wasn't slagging Purple so much in the music. It was the verbal nonsense that went on over the mike sometimes." With the long era of Deep Purple seemingly over, does Rainbow expect to automatically inherit the last vestiges of the Purple people? "We inherited them anyway, whether they break up or not," Ritchie says firmly, showing no trace of surprise when I suggest Purple's had it. "No animosity there, we're all great friends, but the fans went off them I went off them because they're into rock'n'roll. The fans that we accumulated when we started doing `Stormbringer' and that, they're welcome to them, but it wasn't many." If Rainbow's current line-up — Ritchie, Cozy Powell, Ronnie Dio, Jimmy Bain, and Tony Carey — stay together awhile, they may even eclipse Purple in popularity. The band is amazingly tight and enthusiastic, and it's to Ritchie's credit that he went out and assembled a band of equals, rather than taking the easy route and lining up a bunch of anonymous lackeys behind him. There are no sidemen in this band. "That's an ego thing. You've got a lot of bands — I don't want to mention any names — but certain three-pieces that are out that just have one guitarist, and it's called his name, yet the other guys do just as much. That's why we're trying to drop our name, the Blackmore part. "That's just there to let the people know I'm in it, the followers, because we want as many fans as we can get from the beginning. Once they've seen us, then they know that it's not my band. But at first it has to appear that way so people are interested." Rainbow already has a solid foundation of support, but they also seem to be taking aim at a huge bunch of older heavy metal maniacs who grew up on Purple and the like from the earliest days of the music, but who have become alienated by the upstart bands like Kiss, Aerosmith, etc., who somehow cannot relate to the pioneer fans of heavy rock. "It must be weird," Ritchie agrees. "People like Jack Bruce, who's one of my favourites," and unknown to the Kiss kids, etc., "what is he doing? I don't know." Where have all the sixties heroes gone anyway, we wonder? "People have destroyed themselves, basically with drugs, because they're insecure. You've got to draw the line there, without resorting to drugs too much. That's what blows most of them off." That disturbs Ritchie Blackmore. It is a situation that can only lead to an irresponsible attitude toward the audience, something which is deplorable to Blackmore and his mate Cozy, who frankly brings the problem into perspective. "The trouble with most of them, the guys that've made it big, is that they've got to such a point that they figure they don't have to try anymore, so they go onstage and play a bunch of shit and figure everybody's gonna go bananas. "Whereas if you push yourself to the limit every night, then you're always gonna satisfy everyone else. If you don't, that means you're either high on something or you just don't care. The only reason they got to be where they are is because audiences put them there. I think a lot of them tend to forget that. They just go on and play blasè, and say 'Well wasn't that great. Look at me. Here I am. I don't care.' " Quality Control has become a serious problem in rock, especially when you consider all the guitarists these days. The level of competence has risen dramatically in the last ten years, and it's becoming near impossible to distinguish the flashy dans from the bonafide great players.  "I think the people do know," is Ritchie's somewhat optimistic assessment, "but they are a bit confused as why they've supposedly said that they were good. You might go and see Kiss, or whoever -at least they always say that they can't play anyway- but there are a lot of bands going around thinking they're good and they're not. And the kids think 'Well, they're not very good, but they're supposedly good, so I better think that they are good.' It's not until somebody really good comes along and they go `Ah, this guy's really good.' "The guitar players that I imitated were much better than the ones they're imitating now.

"I think the people do know," is Ritchie's somewhat optimistic assessment, "but they are a bit confused as why they've supposedly said that they were good. You might go and see Kiss, or whoever -at least they always say that they can't play anyway- but there are a lot of bands going around thinking they're good and they're not. And the kids think 'Well, they're not very good, but they're supposedly good, so I better think that they are good.' It's not until somebody really good comes along and they go `Ah, this guy's really good.' "The guitar players that I imitated were much better than the ones they're imitating now.People like James Burton and Scotty Moore were way above that, because they were like fifty years old, you know, been playing thirty years. The guitarists who're the so-called greats today, everybody admires them, they're no good. So they're wasting their time listening to those people. They should listen to the oldtimers, and get some kind of foundation there. Everybody today is caught up in a kind of posey, glamour thing. `Well this will sell a few records.' Bang, bang, bang, a few sustained notes, slurred notes…" "The really good guitar players in rock you can name on one hand," Cozy adds. He and Ritchie are in agreement that Jeff Beck is the guvnor of contemporary players, though Cozy's admiration of Ritchie is not far behind. There's not many guitarists about that could've coaxed Cozy out of his auto racing career, he admits, but Ritchie was certainly one of them. "All the really great guitar players most kids have never even heard of. There are very, very few good guitarists left in rock, if you really study it. But then, we'd be able to tell more because we're musicians. Kids in the street probably just don't know what the fuck's happening." "It gives rock'n'roll a bad name, most of the bands that are playing rock'n'roll," Ritchie decides. Being one of rock's premier players though, does Ritchie ever feel like one of the fast guns in town, the big man all the upstarts try to outdraw and build a reputation on? "No. No, I've never run into that. I always listen to all guitarists, but I'm really turned on that much by guitar players. I'm more into string instruments, like violins and cellos. Those people know what they're doing. They devote their life to it. Whereas it's become too trendy in this business. Everybody goes 'I don't want to work. I'll become a guitar player,' and it's gotten ridiculous. "You can sort those guys out because you can tell. People who've been playing about twenty years, like Jeff Beck, the guy's great, and it shows. He wasn't in it to be on the stage. "Everybody's in a band. If they're good, great, but not many of them are. People in orchestras, classical players, they have to be good. There's like a line that they had to cross to get in a really good orchestra. In rock'n'roll, if a guy looks remotely like Jimmy Page he's half there. It's ridiculous." "Most of these musicians sort of spend an hour posing in front of the mirror with a guitar, getting all the arm actions off," says Cozy rather scornfully. "Then they worry about the music last. That's the last thing that they're thinking about, the music. They're in a panic about what they're gonna do that night, and theory and all the musical background goes right out the window." Still, Ritchie is optimistic about the future of rock. "It'll be alright. Everything works out for the best. I think they'll last another six months probably, and then they'll go down hill. "You can't expect, I suppose, the people in the audience to be musicians. I know the bands you're thinking of," mainly the made-up, visually-oriented, non-musical drivel, "and those particular bands will turn people on for a length of time because the people in the audience aren't musicians, and they don't want to go see John McLaughlin. I personally get bored listening to John McLaughlin play. "I'm a so-called musician, but I get bored, 'cause I think `Well, what is he?' That's great, you know, if he really likes it, and there's a minority of people that do like it, but the majority would rather go and see these other bands because they put on a show, and I can see the reasoning behind that, which is valid really. But it's showbiz. It's not music." Still, Mr. Blackmore is not above a gimmick or two himself. "We've got a new one we're gonna use when we hit London. People will find these little metal clasps on the seats, and they're gonna lock them on the seats and we're gonna electrocute the lot of 'em. Especially the critics box." Peter Crescenti, Sounds July 24, 1976 |