|

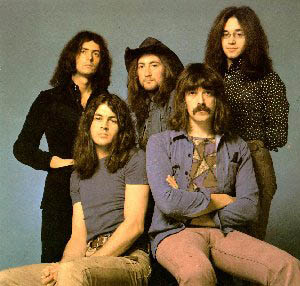

Ritchie Blackmore Black Sheep Of The Family Genius guitarist, arch prankster, ghost-hunter, moody bastard. Hiring and firing band members at will, Ritchie Blackmore is still The Most Difficult Man In Rock.  OCTOBER 1970, Deep Purple are kings of the world. Their fourth studio album, Deep Purple In Rock, is in the UK Top 10, while Black Night, a single recorded in great haste after a night in the Newton Arms near London's Kingsway Studios, has been a hit all over Europe. Hairy bands playing heavy rock are on the rise but Deep Purple are rising fastest. Sixteen months ago their founder members - guitarist Ritchie Blackmore, keyboards player Jon Lord and drummer Ian Paice - have been galvanised by the arrival of a new vocalist, Ian Gillan, and bassist, Roger Glover.

OCTOBER 1970, Deep Purple are kings of the world. Their fourth studio album, Deep Purple In Rock, is in the UK Top 10, while Black Night, a single recorded in great haste after a night in the Newton Arms near London's Kingsway Studios, has been a hit all over Europe. Hairy bands playing heavy rock are on the rise but Deep Purple are rising fastest. Sixteen months ago their founder members - guitarist Ritchie Blackmore, keyboards player Jon Lord and drummer Ian Paice - have been galvanised by the arrival of a new vocalist, Ian Gillan, and bassist, Roger Glover.The original line-up had made inroads into America, but this version - later to be known as the "Classic Mark II" line-up - is poised to ride the coattails of Led Zeppelin. Deep Purple have a similar mix of genius guitarist and high-register frontman and cap a tour of France with a show at the Paris Olympia, for which they are paid £900, their biggest fee to date. However, as the band celebrate at the local Rock'N'Roll Circus Club, the seeds of their destruction are already being sown by Blackmore and Gillan, two hard-drinking 25-year-olds with years of arguing ahead of them. I often blame myself for him," Blackmore told me 25 years later, after several beers and deep into the third cassette tape of an interview. "Ian was a very shy and reserved guy until I did this..." He paused, sheepishly. "For some reason I retain this very childish love of practical jokes. So... he went to sit down and I saw he was a bit drunk so I pulled the chair away.What I didn't realise was that behind us was a big drop of about 15 feet and he fell down - crunched his head. I heard his head go... [Blackmore thumped the table, hard enough to make our glasses jump] on the concrete floor. "I thought it was all over. I thought he was dead. But he got back up, so I go, Are you alright? He goes, Yeah, I just hurt my head a bit. But after that he was never the same." Ritchie Blackmore, though, has remained the same. He will forever be remembered for two things: the riff to Smoke On The Water and being one of the most difficult men in rock. In the first six years of Deep Purple he twice sacked half the line-up. Then he left, formed Rainbow, and went through three singers and over a dozen sidemen in just 10 years. But The Boss From Hell claims he hasn't ever asked more of anyone than he asks of himself: total perfection." I get so angry if people aren't doing their job while I am. And that always comes across as me being moody." Blackmore has been accused of moodiness many times. Had Deep Purple ever managed to make the greatest album of all time, then Blackmore would probably have sighed, complained and picked a fight with the singer. It took him just over a year to tire of Purple's original vocalist, Rod Evans, and bassist, Nick Simper. Their replacements, Gillan and Glover, lasted four years, from June 1969 to June 1973. In that halcyon period, they made a quartet of studio albums (In Rock, Fireball, Machine Head, Who Do You Think We Are) and the double-live Made In Japan. That album, released eight months after Machine Head in 1972, ought to have bought them time, but instead Who Do We Think... was rushed out two months later and, at the very peak of their powers, Blackmore brought the band to its knees.  The blow to Gillan's head can't have helped, but excessive boozing and ill-health made it worse, and the pair were soon stewing in mutual loathing. Blackmore pushed, and Gillan jumped. Years later, the protagonists could reflect.

The blow to Gillan's head can't have helped, but excessive boozing and ill-health made it worse, and the pair were soon stewing in mutual loathing. Blackmore pushed, and Gillan jumped. Years later, the protagonists could reflect.Gillan: "To walk out of the band at their peak would seem stupid but I couldn't see any other way to do it." Blackmore:"I used to call him Oliver Rude because he's very similar to Oliver Reed. He's a very brash individual." Gillan: "No one would talk to me, no one would listen, and no one would tell me to shut up. I must have been pretty impossible for no one to put an arm around me and say, I'm sure we can work this out." The situation became so bad, as Glover recalls: "In the last year of that band's life I don't think Ritchie and Ian spoke one word to each other." By the end of 1973, Blackmore was already making plans to re-invent Deep Purple again. Or leave. Or both. He tried working with Thin Lizzy's Phil Lynott, taking Ian Paice with him to record three songs (which have never seen the light of day) as Baby Face. Lynott was reluctant to split up his band, so Blackmore split his. Then made an almighty mess of it. Wanting only to hire a bluesier lead singer, he ended up sacking Glover, too. After that, if Blackmore couldn't stand Gillan, and couldn't have Lynott, he made the decision to court his new favourite singer: Paul Rodgers of Free. He nearly got him, too, but Rodgers backed off and subsequently formed Bad Company. In came an unknown, bespectacled, acned youth from Redcar named David Coverdale and bassist Glenn Hughes, a seasoned player with the Midlands band Trapeze. Like Doctor Who, the band were back: still called Deep Purple but completely different. Burn, the new line-up's first album, is 30 years old this year and remains one of their very best. But with Blackmore having got exactly what he wanted, it all fell apart again, although this time, he wasn't the only one to blame. The group enjoyed huge success with Burn, becoming the biggest grossing act in the world in 1974 as they promoted it, flying around the States in a Led Zeppelin-style private jetliner and getting paid $75,000 to headline the California Jam festival before a 200,000-strong crowd. With this success came problems. Unknown to Blackmore, Hughes had become a cocaine addict and was developing an ego to rival Blackmore's. But it had all started so well... "Burn was a rock'n'roll band having a great time and playing well," says Blackmore. "Then by the time we got to Stormbringer [the 1974 follow-up], Glenn was really pushing for the R&B bit and David had become much more into it, too. They were taking Jon with them and of course Paicey because he could play funky. Everybody except for me. I was like, I hate this fucking shit!" Blackmore suddenly found himself ostracised by his own band. Come the Stormbringer sessions he began to hatch plans for a solo album. "Ritchie would play us something," Jon Lord remembers, "and go, Do you like this? And we'd go, That's great, let's try it. No, I'm keeping that for my solo album." Stormbringer was a relative flop, the band hardly touring to promote it, and Blackmore sulked through most of the dates until the final shows, when tapes were rolling for what was belatedly released in 1976 as another live album, Made In Europe. However,Blackmore did more than quit Deep Purple: he somehow managed to sack the guitarist of their support band - the Ronnie James Dio-fronted Elf- stealing and reshaping them to be his new band, Rainbow, inspired by the Rainbow Bar & Grill on Hollywood's Sunset Strip. "I was in there with Ronnie getting drunk as usual," recalled Blackmore," and he said, What shall we call the band? I just pointed to the sign. It was lucky we weren't in the Bull And Bush, or any of the other transvestite bars we used to go to..." The band's line-up came to resemble a revolving door. If Blackmore was a difficult bandmate in Deep Purple, he was an impossible one in Rainbow. In their initial run, 1975-'84, the group made seven studio albums with no two albums featuring the same line-up. After the first album (Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow), he retained only Dio as singer. Bassist Jimmy Bain, lasted just one album before quitting. Blackmore couldn't have helped by setting fire to Bain's bed, while he was entertaining a female friend. "I set fire to something and put it by his bed," recalls the guitarist, "and it started catching the bedclothes. But Jimmy didn't see it. So I'm there watching these flames going, Er, Jimmy... But he was too engrossed in the girl. So I try again, Fucking hell, the bed's on fire! He grabbed the bedclothes and threw them out the window" Other members of Rainbow were terrorised in different ways. A long-time fan of seances, Blackmore was delighted that the French chateau in which Rainbow were recording their fourth album, 1979's Down To Earth, was haunted by the ghost of Chopin. "I'd be getting drunk and wondering why no one was going to their room," said Blackmore. "Eventually I realised it was because everyone was so shit scared. They were all waiting for dawn to break. They were so petrified." On one occasion, Rainbow's then drummer Cozy Powell left Blackmore and keyboard player Don Airey in his room while he ran a bath. With the sound of the water running, Powell climbed out of the window, shinned down a drainpipe and across the courtyard to slip into Airey's room. Once there, he lit a candle and danced about beneath a cloak, clearly visible through the window. Don, convinced he had seen one of Blackmore's demons, was reduced to a shivering wreck. The guitarist, unaware that it was Powell clowning, was greatly impressed. That line-up of Rainbow (with new lead vocalist Graham Bonnet and now completed, in a bizarre twist of logic, by Roger Glover) became the most successful, scoring two UK hits with Since You've Been Gone and All Night Long and granting Blackmore the chance to have a serious tilt at the US market. In Europe their profile had risen, too, but suffered badly at the first of two shows at Wembley Arena. Blackmore was unhappy with the audience's reaction and ended the show after just 70 minutes. After 10 minutes waiting for an encore that never came, the crowd vented their fury causing £10,000 worth of damage to the venue. Ten people were arrested and the story made the national press, sealing Blackmore's reputation as a moody bastard who would only give his best if he felt the crowd were doing the same. Yet, while some of Rainbow's fanbase were unimpressed by the group's chartfriendly direction, Blackmore had no such reservations. It wouldn't last. Powell jumped ship, followed by Bonnet. Poised on the threshold of that elusive US breakthrough, Blackmore lost ground again. When I last interviewed him, Blackmore complained at length about almost everyone he had ever worked with. As they did about him, which greatly amused the guitarist. An entertainer, on and offstage, his penchant for wind-ups and practical jokes - despite nearly killing Ian Gillan all those years ago - remains undiminished. Once, while conducting an interview at the Normandie Inn, Long Island, I had listened to him for way longer than my bladder could allow. I finally gave in to the call of nature and asked for directions to the toilet. Blackmore sensed my discomfort and described a long, complicated route. My head reeling, I stood up, turned right, ducked under the bar, ignored the raised eyebrows of the barman, headed down a dark corridor and into the blinding light of the kitchen where a number of bemused chefs pointed me to another door, leading to another corridor, and, ultimately, to a door marked Gentlemen. Inside, giddy with relief, I sighed and let go. From the cubicle beside me Blackmore's voice chirped up, "It's a long walk, isn't it?" He then flushed, left and was sat back at the table we had both just left within 10 seconds. As I followed him he made no mention of the detour he had sent me on, but resumed where we had left off slagging Ian Gillan. Still, the lure of another payday inevitably prompted a reunion with the singer, Glover and the remainder of the Classic Mark II Deep Purple line-up in 1984. It didn't last. Though almost 10 years on, despite stating that he "would rather slit his throat than ever rejoin", Gillan came back for another Deep Purple album and a 25th anniversary tour. Soon Blackmore was accusing him of singing badly, forgetting the lyrics and -in handwritten notes to each of the other three members, "an unprofessional attitude". This time it was Blackmore's turn to quit. For the final time. Years later, he had finally worked out why. "What I wanted was a side issue, it was what the committee wanted. The committee rules. But a committee never got anything done. You cannot go by committee, in rock'n'roll. It does not work." Perhaps, then, The Most Difficult Man In Rock couldn't function if he wasn't simply being difficult. Prompted for the epitaph he'd like on his tombstone, Blackmore offers: "This man has gone to his grave still wondering what the hell it was all about..." That's in line with Roger Glover's theory: "Ritchie's searching for something that turns him on but I don't think he knows what it is. I don't know, maybe he can't handle how gifted he is. He's one of those people that God pointed a finger at and said, You! You're gonna have something that no one else has got." Is this the answer? Is the mystery finally solved? Blackmore simply frowned: "Roger has a lot of stories about God." © Neil Jeffries, Mojo December 2004 Black Night Eyewitness Nottingham 1981 What better way to spend a night in Nottingham with Ritchie Blackmore, a Ouija board and the ghost of Room 211? Like many artists from the 60's - Joe Meek, David Bowie, Jimmy Page - Ritchie Blackmore had a keen interest in the supernatural. I was (un)fortunate enough to attend several of his seances and went for being a total sceptic to cautiousluy open-minded. On one occassion on Rainbow's 1981 tour, I joined Blackmore and a cast of liggers in the candle-lit dining room of an old fashioned hotel in Nottingham. With a makeshift Ouija board and glass on the table in front of us, we jokily asked the usual questions - "Is anybody there?", "Have you a message?"Yet very quickly the atmosphere changed. The upturned glass started moving in an almost agitated manner. Blackmore fired off a series of questions, but the glass just kept spelling out "Room 211". One of our party, an ageing rock chick nicknamed The Avon Lady, began asking questions: "Tell me who you are?""Do you have a message for me?", while staring up the ceiling in a pantomime fashion. The response was immediate: "Fuck off you old hag and die like your mother!"The glass promptly flew off the table and, to add to the drama, a burning log spilled out of the fireplace onto the hearth. The Avon Lady ran out of the room screaming, only to be met at the door by Rainbow's new singer Joe Lynn Turner clutching a lit candle and chanting in a Hammer House Of Horror-style. The newest band-member, he was trying to ingratiate himself with the boss; Blackmore was unimpressed. Once the warbling Turner was ejected, we got back to business. The atmosphere became sombre and the air in the room felt thick and muggy. The only response we could get from the board was "Help me"and, again, "Go to Room 211". The bottle of Johnny Walker Black Label we'd been working our way through didn't quite calm our fears and from here on, the evening became a blur. Nobody slept much. The next day I asked the receptionist about Room 211 and they revealed that in the 1930s, a well-to-do industrialist murdered his mistress in that very room, bludgeoning her to death with a champagne bottle. He was hanged for his troubles. Did we get in touch with the murderer or his mistress? Was I being hoodwinked? Who knows? A week later. Blackmore put a curse on a female journalist at Sounds. A few days after, her hair fell out... but that's another story. © Pete Makowski, Mojo December 2004 |