|

Ritchie Blackmore Rock of Ages IT'S A MIGHTY LONG WAY DOWN ROCK AND ROLL AND RITCHIE BLACKMORE HAS GOT THE SCARS TO PROVE IT. CHRIS CHARLESWORTH TRACES THE TWENTY YEAR CAREER OF A SINGLE-MINDED MUSICIAN.  FOR a guitarist who once trod the boards at the 2 I's coffee bar in London's Soho at the beginning of the 60's, Ritchie Blackmore shows no sign of flagging or giving in to middle age. His latest Rainbow line-up stand high in the charts with "I Surrender" and the band are busy rehearsing in New York for a US tour followed by British dates this summer. As hardy and determined as he is temperamental and opinionated, Blackmore is one of the most technically competent guitarists Britain has ever produced. He's quite at home with the most complex musical arrangements, and just as comfortable performing classical pieces as he is on a rock stage where several thousand watts of amplified electric guitar answer the flick of his plectrum. Ritchie's long career has been marked by a steadfast refusal to fall in with the fashionable trends of the day. This, coupled with his occasionally arrogant attitude to both the press and paying customer — only last year his refusal to do an encore at Wembley started a minor riot — is why he has never enjoyed the critical acclaim bestowed on other guitar heroes like Clapton, Page and Townshend, most of whom would tip their professional hats to Ritchie's expertise.  Ritchie, on the other hand, is not one for complimenting the competition; modesty has never been his style. The only other guitarist he has ever really looked up to was Jimi Hendrix, although he has been known to nod an appreciative head towards country picker Albert Lee and veteran session man Big Jim Sullivan.

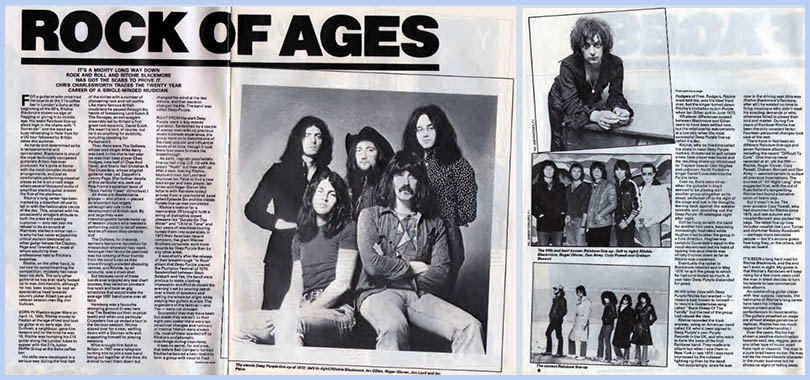

Ritchie, on the other hand, is not one for complimenting the competition; modesty has never been his style. The only other guitarist he has ever really looked up to was Jimi Hendrix, although he has been known to nod an appreciative head towards country picker Albert Lee and veteran session man Big Jim Sullivan. BORN IN Weston-super-Mare on April 14, 1945, Ritchie moved to Heston at the age of two and took up guitar at an early age. Jim Sullivan, a neighbour, gave him lessons and by the time he was 16, Ritchie was humping his £15 guitar along the London tubes to appear with the 2 I's Junior Skiffle Group at the Soho coffee bar. His skills were developed in a serious way during the first half of the sixties with a number of pioneering rock and roll outfits. Like many famous British musicians he passed through the hands of Screaming Lord Sutch & The Savages, an extravagant ensemble led by Britain's first great rock eccentric, David Sutch. (He wasn't a lord, of course, but he'd do anything for publicity, including standing for Parliament!) Then there were The Outlaws, whose lead singer Mike Berry was back in the charts last year (as was their bass player Chas Hodges, now half of Chas And Dave), and finally Neil Christian & The Crusaders, whose original guitarist was Led Zeppelin's Jimmy Page. (For further details of this particular era, seek out Pete Frame's excellent book of "Rock Family Trees" (Omnibus).) All these pre-Beatlemania groups — and others — played an important but largely unrecognised role in the development of British rock. By and large they were interchangeable bands made up of session players who needed a performing outlet to let off steam. And let off steam they certainly did! The Outlaws, for instance, earned a fearsome reputation for misconduct wherever they went. Amongst their favourite pastimes was the lobbing of flour bombs from the band's van as they drove through crowded shopping centres, and Ritchie, by all accounts, was a crack shot. But because none of these bands ever enjoyed any real chart success, they relied on constant live work and took on gig schedules that would make the average 1981 band come over all faint. Hamburg was a favourite stomping ground (it was here that The Beatles cut their musical teeth) and when one particular Crusaders line-up ended a tour in the German seaport, Ritchie stayed over for a year, settling down with a German wife and supporting himself by playing sessions. What brought him back to Britain in 1967 was a telegram inviting him to join a new band being put together at the time. He almost turned them down but changed his mind at the last minute, and that decision changed his life. The band was called Deep Purple. RIGHT FROM the start Deep Purple were a big money operation. Bankrolled by a couple of money men with no previous music business experience, the group went on to become one of the most popular and influential bands of all time, though it took them four years to make the breakthrough. An early, vaguely psychedelic line-up had a big U.S. hit with the poppy "Hush" but then split up after a year, leaving Ritchie, keyboard man Jon Lord and drummer Ian Paice to find a new lead singer and bass player. Ian Gillan and Roger Glover (the latter is with Rainbow today) arrived from a pop/cabaret band called Episode Six and the classic Purple line-up was completed. Ritchie's instinct for a memorable riff brought forth a string of distinctive crowd pleasers like "Smoke On The Water" and "Child In Time" and four years of relentless touring turned them into superstars. In 1972 their American record company, the giant Warner Brothers corporate, sold more records by Deep Purple than by any other artist. It was shortly after the release of their breakthrough "In Rock" album that Deep Purple played the Plumpton Festival of 1970. Sandwiched between Black Sabbath and Yes, the band were anxious to make a lasting impression and Ritchie closed the evening's set by pouring petrol over a stack of speakers and setting the whole lot alight while playing two guitars at once. The organisers of the festival — and Yes — were not amused. Successful they may have been but stable they weren't. In their eight year career there were ten personnel changes and rumours of internal friction were always rife, most of them sparked off by Ritchie's undiplomatic mouthings during interviews. It was no secret, for instance, that before Bad Company formed Ritchie harboured a keen desire to form a group with vocalist Paul Rodgers of Free. Rodgers, Ritchie once told me, was his ideal front man, but the singer turned down Ritchie's invitation to join Purple when Ian Gillan quit in June 1973. Whatever differences existed between Blackmore and Gillan seem to have been settled now, but the relationship was certainly at a low ebb when the most successful Deep Purple line-up called it a day. Ritchie, who by this time called the shots in most Deep Purple matters, threatened to quit unless a new bass player was found and the resulting shake-up introduced ex-Trapeze bassist Glen Hughes and unknown North Yorkshire singer David Coverdale into the Purple ranks. Even so, there were times when the guitarist in black seemed to be playing with another group altogether as he stood, sectioned off to the right of the stage and lost in his thoughts, leaning back against the speaker cabinets and pounding out the Deep Purple riff catalogue night after night. Still he hung on with the band for another two years, becoming increasingly frustrated while Hughes tried to steer the group in a funk direction. Hughes was certainly Coverdale's equal in the vocal department but his habit of lapsing into soul chants was strictly thumbs down as far as Ritchie was concerned. Eventually the rocker in Blackmore rebelled and in May 1975 he quit the group to which he had contributed so much. A year later Deep Purple disbanded for good. IN HIS latter days with Deep Purple Ritchie had wanted — for reasons best known to himself - to record a Quatermass song called "Black Sheep Of The Family" but the rest of the group had vetoed the idea. Ritchie recorded the track anyway, using an American band called Elf, who'd been signed to Deep Purple's own Purple Records in the UK, and who were to form the basis of the first Rainbow band. They made one album but when I saw them in New York in late 1976 1 was more impressed by the colossal lighting rig than by the band. Not surprisingly, since he was now in the driving seat (this was Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow, after all!) he wasted no time in firing musicians who didn't meet his exacting demands or who otherwise failed to please their lord and master. During five years of Rainbow Ritchie has been the only constant factor. Fourteen personnel changes took care of the rest. There have in fact been six different Rainbow line-ups and seven Rainbow albums, including the recent "Difficult To Cure". One line-up never recorded at all, yet the fifth — Ritchie, Roger Glover, Cozy Powell, Graham Bonnett and Don Airey — seemed certain to outlast all previous incarnations. The success of "All Night Long" also suggested that, with the aid of Russ Ballard's songwriting, Ritchie had found a lucrative seam of heavy pop. But it wasn't to be. The ever-amiable Cozy Powell, who had drummed for Ritchie since 1975, quit last autumn and vocalist Bonnett also packed his bags. The latest line-up now includes vocalist Joe Lynn Turner and drummer Bobby Rondinelli — perhaps more bendable people — but it's anyone guess how long they, or the others, will stay on board. IT'S BEEN a long hard road for Ritchie Blackmore, and the end isn't even in sight. My guess is that Ritchie's Rainbows will keep rising for a few more years until the man in black decides to turn his talents to less commercial solo albums. An outstanding guitar player with few outside interests, the hallmarks of Ritchie's long career have been his irritable temperament and his perfectionism in musicianship. (The guitars smashed on stage are almost always geriatrics or replicas; Ritchie has too much respect for craftsmanship.) Over the years, Ritchie has shown a positive disinclination towards soul, ska, reggae, jazz or any other type of music apart from rock or classical. The man is a pure-bred heavy rocker. He may not be the most likeable character in the music business but he shows no signs of fading away. © Chris Charlesworth, Smash Hits - March 19, 1981 |