|

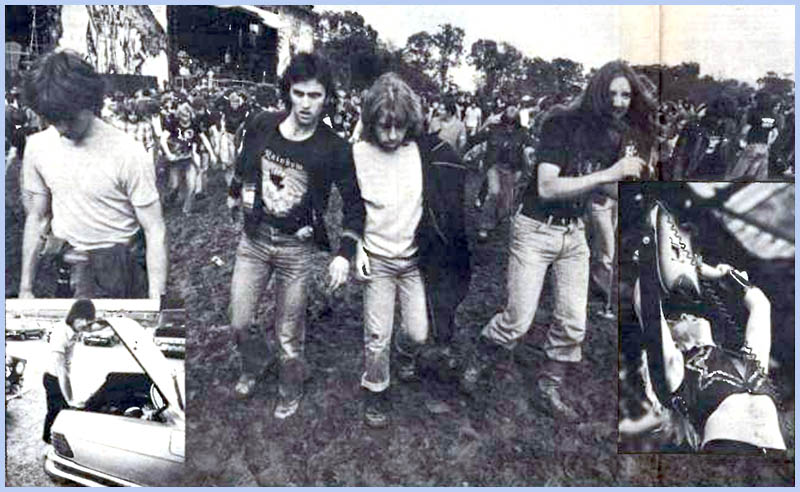

Rainbow Metallic K.O. Castle Donington 16 August 1980 Allan Jones and photographer Adrian Booth wade through the mud at Castle Donington  Fires all across the night sky, like a juvenile vision of hell's final reckoning. The darkness glowing; the flames from the bonfires searching out the stars above. Sweeping up the slope, from the front of the stage, the audience, 60,000 people, they reckon. All day, they've waited for these brief moments of ecstatic communion. For hours, they've nursed desolation while the mud sucked at their enthusiasm. Now, they try to give voice to their adulation. They toss back their heads, yell encouragement; but their voices break and crack in the night's indifference clutch. Behind and above them, searchlights scan the sky like electric moonbeams. The audience cheers again; but it's the sound of people trying too hard to have a good time. On the stage, a man whose hair flaps around his face like a Spaniel's ears, is playing "Greensleeves" through 80,000 watts. I looked at Boot; I looked up at heaven. I waited for someone to beam me out of this comedy, to correct this wild absurdity.... It would look worse later on, but even in the morning sunlight the site of the Monsters of Rock festival at Castle Donington looked like a reconstruction of the Somme. Thursday's rain had all but washed away the festival site, left it smothered in a sticky soup of mud and slime. An American roadie remembered trying to get his truck through the quagmire. "T'ursday, dat road was a river," he said, peeling the mud of his face. "We wuz slidin' down, came slidin' down sideways. Sonuvabitch got washed into dem trees I t'ought we wuz gonna flip over 'n' drown, I never seen such shit." The sun was up now and climbing in a pale blue sky. The mud was still inches thick, murky, cold, slippery, refusing to dry out. Around the stage craters loomed where the ground had been chewed up by the wheels of heavy arctics carrying the PA and the lights and scaffolding for the towers and the generators and all the other paraphernalia needed to wage the rock'n'roll war. The police were patrolling the country lines around Castle Donington. They stared in quiet astonishment at the straggling ranks of the HM army who'd come to witness Rainbow's last stand. Driving down Melbourne Lane to Wilson's Lodge was like driving down an venue that would lead you back into the Sixties. Yak jackets and loon pants bobbed into focus embroidered denim jackets, screamed allegiance to a circus of HM heroes. Mottled faces, blotched red with pimples, trimmed with bumfluff, stared at us. "This is going horrendous," Boot said, his heart sinking like a house-brick in a stagnant pond. I knew he hadn't been looking forward to the gig with any delirious anticipation, but I thought he was laying on the doom a bit thick. We had a map, but no idea where we were going. We were looking for the backstage car park. According tot he map, it was located toward the rear of the festival site behind the Rolls Royce depot. We followed the road along the perimeter of the site for what seemed an other three or four miles. We still couldn't find the backstage car park. "If we go any further," Boot moaned, "we'll be in the next county. Another mile along the track a group of Artists Services security men stood in a group, their yellow tee-shirt shining in the midday sun. "What's this?" Boot wondered. "The border guard?" The Artists Services crew waved us into a large compound. This was the backstage car park. It looked like a huge parade ground, a long breeze-block wall formed the base of an enormous triangle, two rows of buildings traced lines to its apex. There were a few cars sitting like disconsolate cats in the middle of the compound. A few photographers in wellingtons and flak-jackets slick with mud ambled in the sunshine. They looked like they'd just returned from a sortie in the front lines of a particularly messy guerilla war. George Bodnar was there. He had a story that put a humorous light on the day's memorable potential. Apparently the night before there had been a full scale dress rehearsal. Rainbow had intended to climax their show on Saturday night with the most violent explosion they could mount. They brought in cases of gel ignite to do the trick. On Friday, at the end of their rehearsal someone pulled the plunger and the whole lot went off with a bang you might've heard in Nottingham. The stage survived the blast, but only just. Judas Priest's entire backline was blown out. Much of the PA suffered similar damage. One of the lighting rigs was severely buckled. The blast ripped through the tents and caravans behind the stage, throwing people from their seats, deafening those who'd escaped cardiac arrests. Rainbow decided to dump the idea of climaxing their set with such a violent explosion. They still intended to go out with some kind of bang, though. And they were still threatening to pile on as many effects as possible. The hacks and the photographers were requested to sign a document accepting full responsibility for their safety, endemnifying Rainbow and the concert promoters in the event of "injury or death, however caused." Could they be serious? "Oh, yes," said Bodnar, who'd witnessed the previous evening's holocaust. "Last night they nearly blew themselves up ..." "It's a pity they didn't blow themselves up," Boot snapped. "We could all go home, then." I'd never seen the photographer in such a sour mood. The Ariola/Arista mobile home was parked in a corner of the compound. A/A would shortly be hosting a champagne reception for an American group called Touch. Touch were the opening band on the festival bill. Groups of people calling each other dahling milled around the mobile home, pecking each other on the cheek, giggling. The girls from the record company were mostly wearing boiler suits ("How apt," Boot cracked) and cowboy boots. Their newly-washed hair fluttered like hankies in the discreet breeze. Laughter cracked the air like splintering shin-bones as the champagne corks popped and the girls from A/A poured the bubbly into half-pint plastic beakers and served fresh sandwiches to the notoriously gluttonous hacks. "I though there was a recession," Boot said. I wondered what the two million unemployed were doing this morning, as I sipped on the champagne and waved away a wasp. They were becoming such a nuisance. The wasps, I mean not the unemployed. Touch came down from their dressing room and mingled with the record company execs. The hacks dutifully avoided them. Touch looked like a typical American rock band. Which is to say they could've been taken for professional tennis players: you know the look – all over tans, bouncing curls and teeth that dazzled. Pretty repugnant, really; but I enjoyed the champagne. Jennie Halsall said she'd drive us to the stage. Jennie Halsall was the festival publicity director. Festooned with walkie-talkies, radio transmitters and satchells and clipboards, she looked like a member of an SAS assault squad. "Drive us to the stage?" Boot asked bewildered. "Why?" The reason why Jennie was going to drive us to the stage is simply explained. The stage was 20 minutes away by foot. Boot was overwhelmed. "I'm going home," he cried. I wrestled him to the floor and told him I'd rip his heart out if he left without me. Jennie told us that if we didn't want a lift in her we could always wait for the mini-bus. "The mini-bus?" Boot wailed, incredulous. "There's a shuttle. The bus goes every 20 minutes." Boot made a run for the car. I tackled him around the waist before he could hot-wire the motor. Jennie wrestled with the steering wheel of the Mini as it plunged into another pot-hole. A wave of mud splashed across the windscreen. "What you realty need is a Sherman tank," Boot told her. We slid to a halt opposite a series of cement structures that looked like the first line of a military defence network. It's like the Maginot Line," Boot groaned. Jennie gripped the wheel as the Mini skidded down an underpass into the system of bunkers, the walls of which were slimy with damp, the floor of which was inches thick with mud. "My God," Boot whined. "It's 'The Guns Of Navarone' all over again." Jennie parked the car on the other side of the bunkers. We'd have to walk from here. I stepped out of the Mini and immediately wished I'd worn something more sensible than the cowboy boots. The mud whooshed over my ankles, tickled my knees. The audience occupied a gentle incline that looked like a mucky buttock tilted at the sky. Thousands of identically denimed-cald adolescents thronged the slopes; a lot of them already unconscious. "Look at that," Boot said. "Up to their necks in mud and not a care in the world..." We clambered through the mud to the backstage gate, showed our backstage passes to the security and were immediately turfed out. This wasn't entirety unexpected. Blighty rock tests are famously disorganised; what did we expect — something as smoothly co-ordinated as Montreux where we'd been given access passed to everything but the executive lavatories and Elvis Costello's pysche... Touch were on stage, wailing away to no great consequence. Bursting with Seventies' hard rock clichés, their music was all creamy harmonies, histrionic guitar demonstrations, swishing synthesizers. The drummer was wearing satin boxer's shorts and an inane grin. They sang songs about the power of rock'n'roll and their love of ladies who were gonna save their souls. Boot and I wandered through the audience. It was like walking through a vat of coagulating curry. The audience lolled in the mud. Some of the chaps entertained themselves by rolling their girlfriends in the mire. What a great time they must've been having! You wondered what on earth had possessed them to fork out nearly nine quid (plus fares) to sit in a field full of rancid muck on a Saturday afternoon when the pubs were open and the sun was shining. Touch prattled on. "Youaaaaaah neeeaaaand tah raaaaaawwwkanrowwwwwl some!" one of their singers was howling. Down toward the front of the stage, the Ariola/Arista crew were up to their expense accounts in mud, bravely trying to look like they were enjoying the show. Whenever Touch crunched to the end of a number, they clapped and cheered. They were on their own, no one else seemed to care too much for Touch. "Lisssssen! Wontchaaaa lissssen, now?" they sang. Frankly, no, old boy. I headed back to the compound. It would have been a pleasant walk apart from the fact that you could still hear Touch for the first mile. 1 heard them announce their final number. They played their final number. It was received with the kind of silence that would've met the announcement that the rest of the festival had just been cancelled because Ritchie Blackmore was having a new wig fitted. I walked on down the long and winding track, whistling to myself; dodging the wasps; feeling at one with the world... I fell into the compound clutching my heart, coughing blood, my knees buckling beneath me. The walk from the stage to the car park had nearly killed me. I wished that I'd waited for the mini-bus. I clung to a fence breathing hard, my lungs shrivelling. A black Rolls roared into the paddock area, sending up clouds of dust. "Who's this?" Boot asked. "Steve Gett?" A dumpy figure in a striped tee shirt, a droopy moustache and ringlets stepped out of the Rolls. This was Mick Box, Uriah Heep's guitarist. Mick Box headed off to the bar where he'd spend most of the afternoon with his nose in a bun. The A/A caravan was open again. Oh dear; more champagne and sandwiches. What a gruelling day! There was an air of flapping distress in the A/A caravan. The girls from the office were weeping; grown men were white lipped with anxiety. One of Touch has swallowed a wasp! He'd been rushed to hospital. This was the highlight of my day. Sniggering cruelly, Boot and I fell out of the caravan clutching our sides. We watched Def Leppard arrive and swan about the compound before hitting the bar. Boot and I wandered what time Riot would be on. "They've been on for the last 15 minutes." someone informed us. We were so far away from the stage that we couldn't hear a band called Riot playing through 80,000 watts? It seemed unbelievable. We started to walk back to the stage. We looked at the road in front of us, chasing the for horizon. "It's like being in the Foreign Legion." Boot squirmed. We decided to get the mini-bus. We ankled over to the pick-up point. There was no sign of it. We hiked back over to the A/A caravan. Jennie Halsall was there. She radioed the stage, asked for a bus to be sent to the paddock. We hoofed it back to the pick-up point. Eventually, a transit appeared. It was meant to carry seven people; three times that number clambered in. It was like the last bus out of Calcutta. This time we took the scenic route to the stage, along the race track, through the wood. Finally, we reached the festival site. Riot were just leaving the stage. Oh, dear. We caught the same bus back to the paddock. We watched Saxon from the crest of the hill, downwind of the lavatory tents in which a new life-form appeared to be breeding. Saxon appeared amidst a howl of electronic savagery louder than a conversation with Wendy 0. Williams. They have a lead singer called Bif. He makes Ozzy Osbourne look elegant. Bif engaged the audience in something loosely approximating banter. "Whaargnurf snaffnuurgh," he said. The audience cheered. Bif, apparently, had just introduced "Wheels Of Steel," one of Saxon's most popular items. "Ahhhhhhhm talkennnnnbahhhht mah wheeeeeels," Bif roared, sounding like a giraffe being force-fed a Volkswagen. "How many of you are there?" Bif wanted to know. "Forrrty thousand? Fifty thousand — SIXXXXXTEEE THOUSAND!" The response suggested that if there were 60.000 people out there, 59,999 were asleep on their feet. Saxon must've been one of the better bands on the bill; the audience started throwing cans at each other, which is always an encouraging sign. Saxon were playing something called "747 (Strangers In The Night)" when I crept off; they sounded like a cement mixer grinding human skulls amplified through a kitchen window during a light gale off the Orkneys. A photographer from the Belper News joined me in the mini-bus. "I've got a coontry 'n' western concert I'go to t'neet," he said. 'There'll be abou' two hundret people, free beer and a bite t'eat. It'll be grand after this bloody shambles..." The hacks from the rock comics were sitting in the bar consoling each other, waiting for a wandering press officer to happen along to buy us drinks. We were trying to recall the most depressing, godawful festivals we'd been to. Buxton and Bickershawe topped the lists. "Have you seen April Wine?" Boot asked, trying to disengage himself from the small field of mud that had followed him back from the site. "April Wine? Never heard of her," I said, tipping back a stiff one. "Who is she?" "She," Boot said, "is called April, and she's the band that's just come off stage." I looked sheepish: suitably contrite. I looked up. Mick But tucked another bun down the hatch. Possibly Germany's most lethal export since the V-2, the Scorpions may have been the most excruciatingly awful band I've ever seen. If they aren't the worse hand I've seen, it's only because I've forgotten just how miserable Budgie could be. The Scorpions have a drummer called Herman Rarebell who clouts the kit with all the deadly panache of a slaughterhouse butcher swiping defenceless animals over the head with a hammer in a stockyard. Excuse the grossness of the comparison but these boys were the end. They really were damned unpleasant. They made Saxon sound like the LSO, displaying a sence of dynamics that would've dulled the senses of a slug. The punk bands used to be critically pistol-whipped for the sheer repetition of their repertoire and the singular pace with which they attacked all their songs but the Scorpions set new standards of musical inanity. They would've been better off invading Poland. Meanwhile, backstage Ritchie Blackmore had arrived. He roared around the paddock in a black Mercedes, looking as happy as Van Morrison with gout. Outside the cafeteria, Judas Priest's singer, Rob Halford, was poncing about in his leather and studs, cracking a whip like Lash LaRue (Boot inevitably thought the comparison should've been with Danny LaRue...) If I'd know how truly horrendous Judas Priest were going to be, I'd have tried to get the whip around his neck with one end attached to Blackmore's limo... The trips in the mini-bus from the paddock to the stage were becoming increasingly tedious, not to mention dangerous. On the way down to see the Scorpions, the driver hit some kind of obstacle (I was hoping it might've been Cozy Powell, but it wasn't to be); the bus lurched rather indelicately, and I tipped by treble vodka all over the place. Fortunately, most of it went into my pint of lager, so it wasn't entirely lost. Waiting to catch the bus down for Judas Priest's set. I was horrified to find the dependable mini-van replaced by a bloody lorry. A dozen of us clambered in the back, hung on for our lives as we raced down to the stage. The lorry screeched to a halt, we were thrown clear. I refused to tip the driver. I was too busy, anyway, counting loose teeth. Rob Halford rode on stage on a motorbike. Unfortunately, it didn't roar off the front of the stage into the front row of the audience with him on the back screaming blue murder. To say that I didn't like Judas Priest would be like saying that I find Switzerland a little on the dull side, it would be a violent understatement. One of the reasons I love rock 'n* roll is that it can lift your spirits even at its most desperate. Lennon's "Yer Blues" is a howl of anguish, but there's a spirited resilience about it that lifts the heart, makes you want to fight back. Graham Parker's "You Can't Be Too Strong' can cast a shadow, but it refuses to cut off the light. The best rock music is never puerile or sycophantic or deadening: it's an affirmation. Springsteen, Young, Costello, Parker, Duty, Dylan... they refuse to surrender Joy Division, too. Even Echo and the bloody Bunnymen. Judas Priest make my heart sink. Arrogant, mean, small, Judas Priest are about as uplifting as a plunging elevator heading straight for the basement. There's no compassion, anger or rebellion. Just stultifying competence, coagulating energy dying on its feet. The audience spent most of the set throwing mud at each other. So this is what it's come to? They should have been throwing the mud at the berks on stage. As I was leaving someone asked me if I'd enjoyed them. "What time are Rockpile on?" I asked. Back in the bar, I laughed when I started reading my notes on Judas Priest. "Who's from uh... uh, north of Birmin'am," Rob Halford had asked. "Yaaaaah," groaned the people from north of Birmingham. "Who's from south of Birmin'am?" Rob Halford continued, with expert logic. "Yaaaaaaah," wheezed the people from south of Birmingham. "Coooer," said Halford, astonished. "You've coom from a11 over the place." The night fell like the slap of a hand on a coffin lid. Boot and I went back up to our ankles in mud, waiting for Ritchie Blackmore and Rainbow to fire a bullet through the evening's head and put it out of its misary. The introduction was drawn out to the point where at left dramatic tension with its head in a bag and its feet in a ditch and arrived at a blockade of tedium. The tapes played, fanfares sounded through the night, lights raked the stage. There was still no sign of Ritchie and the chaps. Boot was on his knees, sinking into a cloud of boredom. An orchestral overture boomed out over the PA. "Land Of Hope And Glory" erupted through the speakers. It went on longer than a Nick Lowe anecdote. It changed course. "What's this?" I asked Boot as the music droned on like a funeral procession. "Sounds like the second movement." Boot declared, wearily insolent. Over the PA there came a countdown... Ten... nine... eight ..." Then the entire front of the stage blew up like Lenny's nose after a night on the town. Whoooosh! went the flash bombs. The night was bright with explosions. "Looks like it," Boot said, trying to aim his camera over the heads of wildly gesticulating punters. An electronic throb introduced Ritchie Blackmore who bounded to the front of the stage in a black catsuit better suited to a barmaid in a dockland pub. Have these people no style! For a form of music supposedly based on flash and glamour, most heavy metal groups dress like cheap tarts at a works booze up. And if Ritchie Blackmore'd like to give us the address of his hairdresser we'll send some of the boys around to kneecap him. Rainbow played something I took to be called "In The Eyes Of The World". "Sounds like my car," Boot remarked tartly. Ritchie pranced and struck a remarkable variety of poses for a man of his age. His fingers moved so swiftly up and down the fretboard you doubted that he left fingerprints on the strings, I kept wondering why his hair didn't move, why it hung like the flaps of a table, rigid flanks on either side of his face could the rumours be true? Roger Glover, who'd played with RB in Deep Purple, was wearing a panama hat. A sure sign of a Bobby Charlton thatch. His bass amps blew out early on; he could only pose, which he did with some semblance of style and initiative. Ritchie took as many solos as Lee Brilleaux takes swigs from the inevitable bottle(s) of wine during a Feelgoods set. I wouldn't call Ritchie a dictatorial bandleader, but you got the impression that if anyone interrupted one of his mammoth musical tirades they'd end up digging trenches on the Gulag. A video screen to the left of the stage permanently featured our guitar hero In technicolour close up, you could see the concentration he employs to get himself through his hackneyed gyrations. It was revealing stuff the artist at work in an open field with 80,000 watts to play with. My ears were ringing like an alarm clock. "Hello Castle Donington," Graham Bonnet cried. "Are you still drugged out there? Are you sure you're still drugged. You'd better be" I don't know about being drugged. I'd have preferred to have been anaesthetised. And still they raged on! Ritchie played another solo that would've been better off left in the cupboard. Bonnet encouraged the audience to applaud with all the sycophantic panache of the highly paid sideman. Cozy Powell thundered around his enormous kit with the delicate skill of an Irish brain surgeon. When it comes to drummers, I'm a Charlie Watts-Terry Williams man, meself. I like some who boots the music along. About this time. Ritchie played "Greensleeves". It quickly erupted onto another demonic thrash. The audience was beginning visibly to flag. Rainbow were taking on each tune like they'd hated it for years, seemed intent upon pumelling it sideway into the mud Blackmore seemed detached from the whole ritual. The greatest rock guitarists have usually forced their music into areas of humour, drama, sexuality, exclamation, violence and celebration. Blackmore assumes too easily and complacently the cliches expected of him by his audience, he accepts the mundane flight of their imagination. He sound, like he's only ever listened to his own records, accepted their limitations, read only his own good reviews. You're drunk, I'm drunk," Bonnet bellowed. I wished I was drunk. As it happened. I was dangerously sober. Curiously, I began to warm to Graham Bonnet. He was beginning to look increasingly uncomfortable with the parodic idiocies of the material he was forced to give voice to. While Cozy, Ritchie and keyboards nutter, Don Airey increasingly convinced me that they'd left their collective wits in the dressing room, Bonnet was struggling honourably to carry the show. It was a forlorn battle Don Airey's keyboard solo would've put a brick into hibernation He referred to some classical piece. "It's not the 'Sugar Plum Fairy, isn't it?" Boot asked. "No," I replied. "It's still Don Airey". Then Ritchie was back among his flock, bashing his fists on the guitar discovering feedback and buying generally innovative. The sound bounced from PA stacks a11 around the field. It was 1ike listening to someone fart in quadrophonic sound, hardly entertaining, barely credible for a man of Ritchie's advanced years. The volume increased. Orgasmic howls filled the air. And on it went. There was a keyboardsolo that made the Bible seem like a short story. Then it was straight into Cozy "Animal" Powell's drum solo. Coze was playing his last gig with Rainbow. This would be his swan song. He battered around the kit, inventing new clichés as fast as his hands and feet could put them into action. You couldn't have kept my eyes open with pit props. The "1812 Overture" caught up with Animal. Animal roared to a climax. The stage blew up; fireworks impersonating penny sparklers tickled the sky. Talk about an anti-climax. It was like finding yourself in bed with Tuesday Weld and finding that she didn't go all the way... We had been promised a finale used we'd never forget. After Animal's set-to with the penny bangers, we were still waiting for it. The rest of the band returned to the stage. Ritchie blundered into another solo. The band riffed on. Then Ritchie left the stage. This surely was it, Graham Bonnet rapped on, tried to keep us amused. There was still no sign of Ritchie. We eyed the skyline for his appearance on top of one of the towers. Would he fly across the face of the night with a rocket up his arse? Would he be summersaulted into space with an explosion so magnificant it would haunt us forever.... Ah, actually — no. Ritchie ran back on rather tamely. The hydraulic system that would have shot him into the sky had broken down. Ritchie's face appeared on the video screen; he looked set for murder. Rainbow played a slow blues while RB cooled off. Ritchie put his heart and soul into his next solo, but the dramatic impetus had been utterly squandered. Fireworks crackled overhead it looked to be all over. "Almost as pathetic as the Pink Floyd," Boot groused. We were on our way out of the site along with hundreds of straggling survivor. Then Ritchie and the chaps returned. Ritchie set fire to an amplifier, destroyed his guitar. I supressed a yawn. Jimi Hendrix was doing this 15 years ago. He had half the equipment, but twice the talent. As flames from the amplifier flickered behind hint, Graham Bonnet shouted "This is the end of the Rainbow...". "Thank God for that," Boot said, as the mud sucked at our heels like old men sucking at their dentures. © Allan Jones, Melody Maker - August 23, 1980 © Photo: Adrian Boot |