|

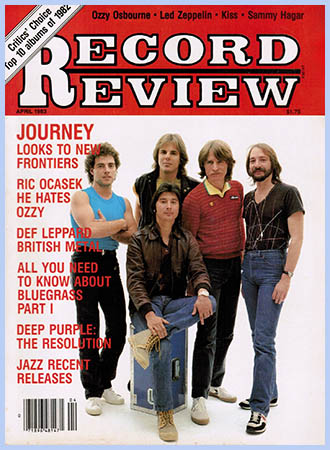

Ritchie Blackmore Deep Purple: The Resolution  At the end of Part One of this rather convoluted reminiscence, Deep Purple found self sans record company in America. The band, needless to say, hurried back to England in hopes of straightening matters out. Adding to the confusion was the departure of vocalist Rod Evans and bassist Nick Simper. Evans emigrated to Los Angeles to be a member of Captain Beyond and Simper joined the Marsha Hunt Band. Simper subsequently rejoined the Sutch band for a spell before forming Warhorse in August of 1970. A series of miscellaneous sessions followed and in April, 1978. he created Fandango. Simper and Evans were replaced by Roger Glover and Ian Gillan respectively and in August of 1969 played their first show with the band at the London Speakeasy.

At the end of Part One of this rather convoluted reminiscence, Deep Purple found self sans record company in America. The band, needless to say, hurried back to England in hopes of straightening matters out. Adding to the confusion was the departure of vocalist Rod Evans and bassist Nick Simper. Evans emigrated to Los Angeles to be a member of Captain Beyond and Simper joined the Marsha Hunt Band. Simper subsequently rejoined the Sutch band for a spell before forming Warhorse in August of 1970. A series of miscellaneous sessions followed and in April, 1978. he created Fandango. Simper and Evans were replaced by Roger Glover and Ian Gillan respectively and in August of 1969 played their first show with the band at the London Speakeasy.This Deep Purple lineup Mark II - Blackmore, Paice, Glover, Gillan, and Lord—provided the most memorable moments of the quintet's career though their debut in a classical genre was little less than embarrassing. Deep Purple/The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Conducted By Malcolm Arnold grew out of the band's classical wanderings on the Deep Purple album. Composed and scored by Jon Lord with lyrics by Ian Gillan, the album was quite an auspicious start for a group finding its legs with a new record label. One wonders that Warner Bros., the new company, did not toss the band out on its collective ear after receiving this as debut product. Originally intended as an evening of "fun," the record holds little for classical or rock devotees. Blackmore was as harsh as anyone about the final results. "I like proper classical. I hate the novelty groups playing with orchestras. Because that's just a compromise. The orchestra's not playing at its best and the band is certainly out of its depth." The band, however, should not take total blame. The group's promoter suggested Lord begin work on an extended piece so the keyboardist penned several notes a week, more for his own satisfaction than in an attempt to write something serious. Lord virtually forgot about the project until receiving a call from this promoter informing him that the piece was to be performed at Albert Hall in September. The month was June. The band rehearsed three times with the orchestra before the appearance and the subsequent recording. When this became the group's first release for Warners many people formed the wrong impression of the band. It may have seemed to Purple followers that the change in personnel had caused a change in direction and that perhaps a mistake had been made. Nothing could be further from the truth. Blackmore talks about those departures and arrivals. "Nicky wasn't constructive and didn't have any ideas and he was an average bass player so he had to go. Rod just wanted to go to America. 1 wasn't worried at all about finding new people because Rod wasn't interested at all and it showed so we could only do better. Which we did with Ian Gillan. Roger we found under a gutter. No, poor Roger. We originally weren't going to take him but Paice said he was a good bass player and we should keep him so I said OK. I think he was trying to prove he could wear clothes less than 10¢. There wasn't one thing on him worth more than 10¢. His shirt was made out of rubber or something, he found his trousers, and his shoes were done up with wire. I couldn't believe it." Nor could one believe the absolute majesty the group created on the classical followup. In Rock realized what the band's earlier recordings never did—the creation of a true musical form and style. One may have tagged this as heavy metal but Purple always embodied more discipline, technique, and structure than the other groups which thrashed around them. Where the previous releases oftentimes lapsed into ineffective spaces, In Rock maintained a level of quality which truly propelled it into the Must Haves in anyone's rock collection. Released in June, 1970, the album was accompanied by a media blitz from Warner Bros. Full page ads with the band's faces carved in rock a la Mt. Rushmore underscored with POWER TO D. PURPLE headlines sent this album to number 4 in the English charts while America, slow to catch an, kept it at 143 (faring only slightly better than the Orchestra album had at 149). It was their high watermark, their 10, their brain fryer. "Speed King," a re/arranged "Good Golly Miss Molly," kicked it off, a frantic riff of lunging power. "Bloodsucker" is perhaps Blackmore's most spellbinding use of vibrato; the sound of his Fender Stratocaster is magical. "Child In Time" is the anthemic ten-minute piece which builds to a screaming climax. "Flight of the Rat," breaking open Side Two is an Ian Paice showcase, highlighting the left-handed drummer's masterful stick and bass drum control. "Into the Fire," "Living Wreck" and "Hard Lovin' Man" are all manic riffs infused with Blackmore's triggered guitar lines and Lord's sorrowfully screeching guitar.  "I was tired of playing with classical orchestras and I thought "This is my turn," says Blackmore of the In Rock sessions. "Jon was more into classical and so he had done that and I said I'll do the rock. And whatever turns out best we'll carry on with. I said if this record fails then I'll play with classical orchestras for the rest of my life. It (In Rock) was a very good Lp; everything was about 1,000 miles an hour. It was good, objectively speaking. Everything on there was good: there wasn't one track I really hated."

"I was tired of playing with classical orchestras and I thought "This is my turn," says Blackmore of the In Rock sessions. "Jon was more into classical and so he had done that and I said I'll do the rock. And whatever turns out best we'll carry on with. I said if this record fails then I'll play with classical orchestras for the rest of my life. It (In Rock) was a very good Lp; everything was about 1,000 miles an hour. It was good, objectively speaking. Everything on there was good: there wasn't one track I really hated."Lord, years later while working with Whitesnake, talked about this polarity. "In Purple it was either totally one thing which was soloing like a mad mother or being a rhythm guitarist keyboard-shaped. And that was fine with Purple, it was a big part of the sound." While this student of journalism felt In Rock represented Purple's loftiest moment, singer Ian Gillan felt otherwise. In Rock was Gillan's vocal debut with the band in a rock context (he had appeared on the Orchestra affair) and he sensed that it wasn't until Fireball, the successor to In Rock, that he band came to fruition. "I always had big debates with Ritchie and Jon and Roger and little Ian about our best album," expressed Gillan. "My favorite Purple album was Fireball and the reason I like it so much was from a writing point of view it was really the beginning of tremendous possibilities. Some of the tracks on that album I think are really, really effective. In those days before it was being called heavy rock or progressive rock, it was still being called rock, and I really thought some of the tracks on there were progressive rock numbers. I thought it was a shame we didn't continue with that expression in our writing as opposed to the sort of formulated approach on our later albums." Fireball, released in September, 1971, must have struck audiences in a similar way because it climbed to number one in the English charts on the strength of single releases "Strange Kind of Woman" and "Fireball." It also made its way to #32 in the American annals, far and away the most successful Purple album to that point. It was an exceptional album. The title track was a classic display of the brilliance of drummer Ian Paice. "No No No" opens with a heavenly sounding guitar and Blackmore incorporates more feel into these first 32 bars than most players realize in a lifetime. The passion in his playing is so understated as to create chills. Side Two is somewhat weaker than the first (although "Anyone's Daughter" on the opening side is a real throwaway bit of funk nonsense). "The Mule" is the by now recognized guitar/organ orchestrated line; "Fools" is a filler; and "No One Came" is a steal from Hendrix' "Stone Free." This album, like In Rock, was produced by the band. Under pressure from management to turn out an album, the band fails to generate the excitement and sheer energy of In Rock. Blackmore expounds on the album's shortcomings. "I got bitter about that, this pressure from management. Fireball was a bit of a disaster. We had no time, we had to play here, and there, and there, and we had to make an Lp. I thought 'If you want an Lp, you've got to give us time.' And they wouldn't so I got a little bit bitter about that. I just threw ideas to the rest of the group that I thought up on the spur of the moment." The following album was recorded at a much more leisurely pace. The group was granted a two-month reprieve from touring by the management and the resulting album shows both the power Purple managed to create in the studio as well as their mastery of studio sound. Machine Head, like its immediate predecessor, spiralled to the number one position in the British charts and all the way to seven in America. Where Fireball failed in translating the raw edge present on In Rock, Machine Head not only delivered this primal side of the band but framed the band in one of its strongest musical moments since its birth. Blackmore's playing is sharp and rapacious and on virtually every track he provides evidence that he is one of the most formidable musicians ever to play guitar. "Highway Star" has since become one of the band's anthems and his harmonized solo is in virtually every guitarist's repertoire; on "Maybe I'm A Leo" he produces a delightfully languid passage; his clean picking on "Pictures of Home" is staggering; and the opening muted notes of "Never Before" never fail to enchant. All three tracks on Side Two are legendary — "Smoke On The Water," "Lazy" and "Space Truckin'." While the band was granted a hiatus from touring in order to deliver the album, Machine Head was not without its problems. The band, with help from the Rolling Stones mobile studio, retreated to Montreaux, Switzerland, as site of recording. Initial plans were to record the album at the casino in Montreaux but a fire destroyed the gambling hall and in its wake $48,0130 worth of equipment belonging to Frank Zappa (the Mother had been performing on stage when the fire erupted). With deadlines to meet, the band scoured the city in hopes of finding a new location. After passing on a secluded chateau in the mountains, a bomb shelter, and a mammoth cavern once housing war treasures, they chanced upon the Grand Hotel, an elite but nearly empty building with hallways wide enough to accomodate the gear and a spiral staircase which might double as an echo chamber. A corridor was partitioned and mattresses were brought in to create a pseudo-studio. Because there was no pressure from a clock ticking away studio time, Machine Head was completed in an astonishing three weeks. "It was a great Lp, I thought," agrees Blackmore. "We had ideas, Ian Gillan, myself and Roger. It became a trio writing then; Jon stepped back and Ian (Paice) just gave percussive ideas. So it was a trio by Machine Head." Indeed, Blackmore's guitar dominates the album and while his solos tend to obscure the other instruments, Ritchie's rhythm playing is similarly moving. Almost mechanical by style, his accompaniment playing is rigidly structured but by no means lacking in feel. The introductory sequence of "Smoke On The Water" is a beautiful example of his hammer-type rhythm. He, however, fords backing tracks anything but satisfying. "I hate rhythm tracks; they bore me silly. That's why most of my rhythm tracks are very clinical. Because I'm so bored with just trying to get the thing right. I just love the part where it comes to putting my bit on there. I don't like recording too much; it's too clinical. A lot of people love it because they can edit the music but when they get on stage, they're lost. My way of thinking is the opposite. "I was listening to some of Purple's stuff and I thought I was better than that. It's very sketchy but at the time it was the best I could do. Because we usually only had three weeks to get an Lp and there were so many egos involved too. "I go through similar things as Jeff Beck. I'm never happy what I'm doing. He's always going 'Ah, what to do?' and I'm always going 'Ah, what to do?" Apparently Blackmore, and the rest of the band, did not have a clue in terms of what to do for their next album because Who Do We Think We Are! represented their sorriest work yet. Lacking in emotion and energy, devoid of any inspired playing or singing, and minus any salvageable material save for the single "Woman From Tokyo," this February, 1973, release signalled the ultimate disintegration of the band. Blackmore did not talk to organist Lord one time during the entire recording and the result is an apathetic album bearing no similarity to earlier Purple releases. "Super Trouper" and "Smooth Dancer" are pablum, the former stealing the swirling effects pioneered on "Itchycoo Park" by The Small Faces, while the latter is an obvious rip from the band's own "Speed King." They could not even imitate themselves convincingly by this point. "Rat Bat Blue" sports a harpsichord solo sped up and comes out sounding like some Chipmunks outtakes. "Place In Line" is a sloppy blues with a barely mediocre guitar solo and half-baked organ line. "Our Lady" sounds like a church sermon. The album — recorded in Germany (Walldorf) and Italy — was interrupted several times by tours of England, Japan, and the United States and this lack of continuity is a glaring flaw of the album. Even with record company support ads heralding "A Pound of Purple for Every Gram of Vinyl. You Get It With Who Do We Think We Are! Deep Purple's Finest Massive Album Will Help You and Warner Bros. Records Whip the Energy Crisis," this album barely makes it to the level of acceptable. It did chart at number 4 in the United Kingdom and number 15 in the United States which goes to show there is absolutely no accounting for taste. "Everybody refused to write with everybody else," offers Blackmore in explanation of the sorry state of this album. "I was even holding back ideas. I was saying, 'I'm not going to give you this because it's going to another thing' (Rainbow?). I was turning out crap and so was everybody else. It was rubbish, it was bad. It was a waste of time." Purple, for the most part, seemed to be on a rock and roll roller coaster: In Rock was up while Fireball was down; Machine Head ascended while Who Do We Think We Are! descended. So, is it safe to assume that the band's next release, Live in Japan, would be one of the up ones? Assumption correct. Live in Japan, recorded there during a three-day period from August 15 to August 17 in 1972, was their first live album — as well as their first double package — and as this author stated in the introduction of Part One, Purple cranks on this album like few others ever have. The tracks drive, the playing is possessed, and like few live albums, the versions here are as strong if not stronger than the originals. The material was culled mainly from the Machine Head album and while the band did plan initially to pull songs from all three nights, "Smoke On The Water" is the sole track recorded at the band's first night in Osaka. It seems Blackmore, furious with his own playing, destroyed his guitar. The album was recorded on an eight-track machine and mixed by Roger Glover and Ian Paice. Blackmore, never really happy with any recorded work, has a particular dislike for live albums. "I never listen to them. They're dead and buried. Made In Japan was alright. I think our live Lp's, as live Lp's go, are rubbish but compared to all the other groups who put out live music, they're brilliant." Apparently the success of this album was not enough to allay the problems mounting within the band. For singer Ian Gillan it was a growing dislike of the creative direction of Purple forcing him to leave. "We had a slightly formulated approach to our later albums," Gillan confesses. "I don't think that can be denied by anybody. Every album started with the same tempo number and that's just the way it was. That's one of the reasons why I left. Because I became stagnant and we became so entrenched between these parallel lines beyond which we dare not pass because that was the Purple identity and the Purple image. We were really restricting our means of expression. It became frustrating and I think that's one of the reasons Ritchie later left." While many people may have thought there was bad blood at this time amongst the various members, Gillan denies the charge. "Oh, no. It's just that Purple was so personal. I've never had such experiences on stage with such players. I was literally moved to tears when I first worked with Ritchie on stage. Unbelievable." Following his departure, Gillan formed a band under his own name (originally to be titled Shangrenade) in September, 1975. He recorded his first album ten months later and called it Child In Time. He went on to cut several more including Clear Air Turbulence; Scarabus; Live In Budokan Vols. I & II, and after changing the band name to simply Gillan in August, 1978, recorded Gillan. Accompanying Gillan on his departure was bassist Roger Glover. Glover, who left presumably to exercise more creative control, became head of A&R at the Purple label and went on to enjoy success producing Rory Gallagher, Elf, Gillan, Nazareth, Status Quo, Judas Priest, and David Coverdale. He was commissioned to write The Butterfly Ball which grew into a book, film, and live Albert Hall performance. Glover put out one solo album called Elements and he is currently playing with Blackmore as bassist in Rainbow (more on them later). The new recruits were vocalist David Coverdale and bassist/vocalist Glenn Hughes. Coverdale, born September 22, 1951, had been in several bands before joining Purple but nothing which remotely matched their level of success. He attended art college in 1967 and 1968 while playing with The Skyliners. This outfit changed its name to The Government and opened for Purple at Sheffield University in 1969. Other working bands included Harvest, River's Initiation, and The Fabulosa Brothers. When the word went out that Deep Purple was searching for a singer, he mailed a tape and landed the spot. Even Blackmore, a person who is rarely excited, was bubbling over Coverdale's addition to the band.  "I'm excited about this guy who is singing. He's just so good. It's not putting other singers down but I've never heard a singer sing like that. Paul Rodgers is, I think, the best singer around (Rodgers was on the docket to join the band at one point) but I think Rodgers will hear this guy and go 'I like him."

"I'm excited about this guy who is singing. He's just so good. It's not putting other singers down but I've never heard a singer sing like that. Paul Rodgers is, I think, the best singer around (Rodgers was on the docket to join the band at one point) but I think Rodgers will hear this guy and go 'I like him."Bassist Glenn Hughes, the other new-comer, started his career as guitarist for a Birmingham-based band called The News. He switched to bass with a band called Finders Keepers and then joined Trapeze with whom he spent the bulk of his career. They recorded several albums including Trapeze; Medusa; You Are The Music.. We're Just The Band; and a U.S. compilation called Final Swing. Trapeze toured America extensively supporting the Moody Blues and at one point Hughes was offered a spot in the then embryonic Electric Light Orchestra. "It killed me to leave the band; I didn't want to leave the band," chimes Hughes about his exiting of Trapeze. "But I couldn't refuse the money (of the Purple offer)." Coverdale and Hughes fit splendidly with the remaining Purple members and the resulting album, Burn, represented a more contemporary version of the In Rock affair. That is, it was merciless in its passion and yet the quality of song was more in evidence than on the Rock album. Burn, along with Machine Head, was the only DP album to make it into the coveted Top 10 in both America and Britain (9 and 3 respectively). The band in its new form hibernated in a place called Clearwell Castle, a rehearsal studio where the likes of Joe Cocker and Bad Company rehearsed, and while they should have been preparing material for an album, found themselves engaged in extra-curricular activity. "We just played football and had seances all the time," Blackmore recalls. "Nobody bloody ever did anything. Jon never used to get up until 6 at night, go straight out for a meal and stay there eating until 10 o'clock at night, go down to the studio and play and by 10 o'clock at night I'd be pissed off and go to bed." The band realized it only had four days before entering the studio and in that time they produced some of the most memorable Purple material ever. The title track is one of Blackmore's most engaging employments of the block chord style he is now so famous for ("Smoke On The Water"; "Man On The Silver Mountain" et al). The solo it devastating and includes the other Blackmore trademarks—classical chord sequences, staccato picking, vibrato bar manhandling. The following two songs on Side One (the album opens with the title track) titled "Might Just Take Your Life" and "Lay Down, Stay Down" are similarly moving. Other standout cuts include "You Fool No One" and "Mistreated." The Purple roller coaster had reached it zenith and there is only one way to go from the top. Growing pressure from the recordcompany — to produce more albums per year than the group was capable of writing — forced Blackmore to show his hand. His discontent was growing and with the release of the highly R&B influenced Stormbringer in November of 1974, the guitarist was near beside himself. Both Hughes and Coverdale were highly influenced by black music and these strains came out on the 1974 release. Recorded at Musicland in Munich by Mack (Queen; Billy Squier; Sparks), the album really has little to defend itself with. "Lady Double Dealer" lays claim to the strongest track and along with "High Ball Shooter' there is little else here to speak of. About the album Blackmore insisted "This is as far as it goes. I don't like black funk. It bores me to tears. Back to rock and roll for the next Lp." An album which would find Blackmore already rehearsing with a new band to be called Rainbow. Adding to his dislike of black styles was his disappointment in the band's reluctance to record "Black Sheep Of The Family," a song originally covered by Quatermass. Claiming they only wanted to record in-house tunes they passed on it and sent Blackmore scurrying to vocalist friend Ronnie Dio (then with Elf, a band which opened for Deep Purple) in order to record it. The song came out "brilliantly" and from this an album was born. "It was so refreshing to be working with new musicians and to have a rapport of which I didn't have with Deep Purple. Purple got, myself included, very blase about other people's ideas. It was a case of 'Well, let's just shove down anything and make a bit of money.' And it was getting to that stage." Ritchie Blackmore quit Deep Purple in May, 1975, and formed Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow with vocalist Ronnie Dio. Since its inception Rainbow has recorded seven albums and the catalog include: Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow; Rainbow Rising; Rainbow/On Stage; Long Live Rock 'n' Roll; Down To Earth (the first with new vocalist Graham Bonnet); Difficult To Cure; and Straight Between The Eyes (the latter two with singer Joe Lynn Turner). All has not been sunny for Blackmore and Rainbow. Numerous member change: (Blackmore, admittedly, is not the world's easiest musician to play with though his sense of creativity is undeniable), uneven albums, and disappointing tours has kept the band from reaching the higher echelons. The group's last two albums, particularly the most recent, have shown true signs of revitalization (Turner is a sizzling singer) in terms of material and proves that the guitarist is still capable of penning works of art. With the departure of Blackmore, the history of the band had not long to go. Tommy Bolin, a resident of Denver, Colorado, formed Zephyr in 1967 and its five year life saw the release of three albums Zephyr, Going Back To Colorado; and Sunset Ride before the group disbanded it 1972. He then joined The James Gang as replacement for Joe Walsh (turning out Bang and Miami). After Dave Clempson (formerly with Humble Pie) was found unsuitable, Bolin was invited to audition for Purple. He landed the position. Tommy's sole recording with the band (including several tours) was Come Taste The Band an October, 1975 release on which he wrote or co-wrote eight of the nine tunes. 0f these, "Gettin' Tighter" was the only track of real urgency. The group embarked on one final work tour taking in America, Europe, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Hawaii, Australia and Japan and lasting from November 1975, to March of the following year. In July of 1976, the band was officially laid to rest. Jon Lord (during his stint with Purple the organist had been involved in many outside projects including Gemini Suite; Windows; First Of The Big Bands; and Sarabande) and drummer Paice formed P.A.L with keyboardist/vocalist Tony Ashton. David Coverdale went on to form White Snake which would later also enlist Lord and Paice. Glenn Hughes reformed Trapeze and most recently has formed the Hughes Thrall Band with renegade Pat Travers guitarist Pat Thrall. Tommy Bolin stepped out to form the Tommy Bolin Band and two wonderful solo albums titled Teaser and Private Eyes. Bolin died of a drug overdose on December 4, 1976. An autopsy revealed several drugs in his bloodstream but heroin overdose was the primary cause. This, then, is the Deep Purple legacy, the chronicle of one of the world's most creative, successful, and controversial bands. The Guineas Book of Records listed them as the "World's Loudest Band" but this hardly seems fitting for a troupe of this caliber. Perhaps Ritchie Blackmore wrote the group epitaph when he claimed "We have a lot of people who hated us because we were so demanding. If you don't like the music you've got to turn off. You just can't talk over our music and we didn't want anybody talking over anyway." © Steven Rosen, Record Review - April 1983 |