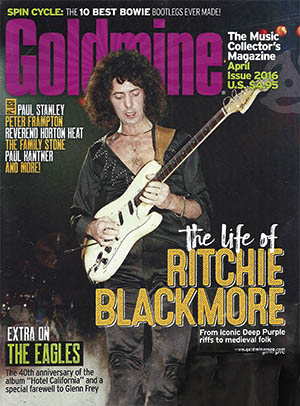

|

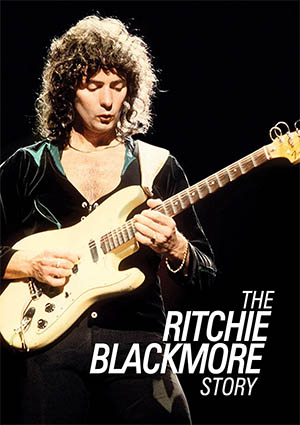

Ritchie Blackmore Ritchie Blackmore ... this is your life!  With the release of Ritchie Blackmore's life story on DVD, the legendary guitarist looks back on his musical career with great pride.

With the release of Ritchie Blackmore's life story on DVD, the legendary guitarist looks back on his musical career with great pride.Two hours-plus of in-yer-face Purple, Rainbow and a great deal more; new interviews with the man himself, plus a who's who of fellow travelers; the blurb on the back calls The Ritchie Blackmore Story DVD "the definitive story of a true guitar legend." But there's one person who won't be watching it. Blackmore himself. "I haven't seen it myself, as I'm one of those type of people who, when I see myself in film ... I'm too self-conscious. So I don't watch videos or documentaries unless they're about other people." Still he was happy to spend the time necessary to talk through his career, not necessarily to "set the record straight” (fans would say he doesn't need to), but more to tie together the multitudinous skeins of a career that has hit more musical styles and phases than many musicians even live through. Born in the western English town of Weston-super-Mare on April 14, 1945, but raised in Heston, a suburb of west London, Ritchie Blackmore was 12 when he got his first guitar … but, as he explains early on into the film, he'd been refusing to smile for the camera for a lot longer than that. He tells a great story about his mother trying to coax a grin out of him for a photograph, and Ritchie demanding to know why. He was 5 at the time. That first guitar, a black Framus acoustic, cost his parents 5 pounds, and it cost Ritchie a year of classical guitar lessons, a condition laid down by his father. But the boy moved fast. A poor student by his own admission, he had just one ambition at school. He didn't care what the teaches thought of his scholarly efforts. Just so long as they acknowledged he was a great guitarist. He found a tutor of his own. Opening the phone book, he looked up his favorite guitar player, Big Jim Sullivan, and discovered he lived just a bus ride away. Soon, Blackmore was knocking on his hero's front door, stars-in-the-eyes and guitar in hand, and the lessons began almost immediately. Any guitarist, Big Jim told his student, could parrot the solos that others had recorded. But a great guitarist created his own. At 13, Blackmore was playing in a skiffle band; at 15, he was working at nearby London airport, learning to service radio transmitters and saving for a new, "real," electric guitar, a Hofner Club 50. His first band, the Dominators, was formed with school friend Mick Underwood; others, with names like the Satellites and Mike Dee & The Jaywalkers followed before 1962 brought him a taste of minor stardom, as one of Screaming Lord Sutch's ultra-theatrical Savages. And by year's end, he and Underwood were members of the Outlaws, house band for Britain's most pioneering record producer, Joe Meek. More than half a century later, Blackmore recalls those pioneering days for Goldmine — and fills in a major gap in the DVD, which effectively leaps from Blackmore's birth to the writing of "Concerto for Group and Orchestra" in the first 12 minutes. GM: What first interested you in guitar playing, and who would you say were your earliest influences? Could you tell us a little about what you saw/heard in them that was so exciting? RITCHIE BLACKMORE: The excitement of rock 'n' roll. Elvis Presley. Tommy Steele was a big idol of mine. Early influences were Duane Eddy, Buddy Holly, Cliff Richard, The Shadows, Hank B. Marvin and listening to Radio Luxembourg on my transistor radio. The energy and the feeling was unlike anything I had heard before. At that point anything to get away from school was fine by me. GM: Given your interest in non-rock music, were you ever involved with any of the folk and blues clubs that were around when you were young, and which were maybe more welcoming to older forms of music? RB: I used to play in a band and we would go down Chislehurst caves and listen to trad jazz bands, and I always wanted to be a beatnik or as they called them then, a bohemian. I used to wear tight jeans and a very long pullover, which was shredded so I looked homeless. I liked the carefree attitude. I started playing In a skiffle group. I started on a washboard and progressed to a dog box then on to an acoustic guitar when I was 12 or 13. GM: Was there any single thing, or perhaps sequence of events, that placed you firmly on the "rock” path? Looking back, were there any/many opportunities to move in a different direction that you could have taken up, but for whatever reason didn't? RB: Not that I recall. My first major inspiration from seeing live bands was Nero and the Gladiators at South Hall Community Center. They played rocked-up classical music which had a great impact on me, and that was my first introduction to playing classical music in a hard rock sense.  They were doing songs by Grieg — "In the Hall of the Mountain King”… czardas of which Screaming Lord Sutch would introduce that song saying that it was written by Richard III with his back to the fire — consequently it was called "Charred Ass." But I digress ...

They were doing songs by Grieg — "In the Hall of the Mountain King”… czardas of which Screaming Lord Sutch would introduce that song saying that it was written by Richard III with his back to the fire — consequently it was called "Charred Ass." But I digress ...There were weeks when Blackmore and the band found themselves playing anything up to half a dozen different sessions a day, simply waiting around the studio while Meek ushered another young hopeful or old pro into the room to record. And, when they weren't in the studio, the Outlaws were out on the road, backing one or another of Meek's protégées or, for a few weeks during 1964, accompanying the legendary Gene Vincent, as he undertook another of his periodic comebacks. The band recorded in its own right as well, running out a glorious chain of singles under Meek's tutelage that included a positively violent rendition of Jerry Lee Lewis' "Keep A Knockin'" — subsequently termed, by British DJ John Peel, as the first Heavy Metal record ever made. Joe Meek is such a "creature of legend” today, and at the time he was certainly several steps outside of the music biz norm. Did Ritchie believe The Outlaws were working with somebody "special”? Or, contrarily, did he feel a home studio filled with homemade equipment was less than the band merited? RB: No! I felt that I was working with a very talented brilliant producer. The Outlaws would do most of the session work — not all — for Joe Meek, but enough to make a very good living. Joe was quite temperamental but anybody who has that talent usually is. I think what got to Joe Meek at the end was losing the case for "Telstar,” which he wrote and a French man claimed that he wrote it and took him to court and won the case, I think. That is what I heard anyway. GM: So many of the guitarists on the "scene” at the time have since become legends; Clapton, Beck, Page, yourself, etc. Were there any who you particularly admired? Who do you think should have received more widespread recognition than they ultimately did? RB: There are two guitarists that come to mind immediately (from) when I was that age between 15 and 16, and that would've been Albert Lee and (Big Jim) Sullivan, who taught me a lot because he lived in the neighborhood. But there were many others like Richard Harding; Mick Green of the Pirates; Tony Harvey of the Gladiators; Colin Green; Roger Mingaye, whom I played with in the same band when I was 15 — he was a guitarist way beyond his years. I think he moved to Australia. Bernie Watson — he played with Nicky Hopkins. But there were so many, and there are probably a few I've forgotten. Blackmore released his first solo single, "Little Brown Jug,” in 1965, then formed a new band, the Musketeers — an instrumental three-piece whose stage act opened with the musicians fencing. It didn't last long; neither did stints with Neil Christian's Crusaders or Screaming Lord Sutch's Roman Empire. Other musicians, however, were coalescing around him — Nick Simper, bassist with the late Johnny Kidd's Pirates. Drummer Ian Paice and vocalist Rod Evans of The Maze, and keyboard player Jon Lord of The Artwoods. Slowly a new band began to coalesce; even more slowly, it metamorphosed into Deep Purple. The early Purple notion of combining rock and the classics is often seen as Jon Lord's baby, but Ritchie's own musical interests also leaned in that direction. Goldmine asked Ritchie how the two of them differed in terms of what they brought to the band, and would he describe it as a compromise? RB: It was a compromise in a way. (Jon's) ideal of playing classical music was performing with orchestras. Mine was just playing famous classical or old melodies rocked up. I wasn't that keen, to be quite honest, of doing the concertos because it was very structured and I'm not a good reader of music and when playing with classical musicians, they expect you to play very quietly, otherwise they say you're too loud. It's difficult to get a good sound playing very quietly when it comes to rock 'n' roll. I remember one instance when we played the Albert Hall, playing one of Jon's concertos, and there was a 24-bar improvisation section where I was to extemporize over the two chords played by the orchestra. Afterward the conductor pulled me aside and told me that the 24-bar break that I was to improv over went on for like 50 bars and I had no idea and he had to hold the orchestra back from coming in. The orchestra was very perplexed to what I was doing, as it wasn't worked out. The conductor was great about it, but he had a hell of a time holding the orchestra back from playing until I finished. Lord's "Concerto for Group and Orchestra" became Purple's fourth album, after three earlier sets saw the original lineup shatter, and then come together again around vocalist Ian Gillan and bassist Roger Glover. Purple were off and running and, over the next five years, a succession of further albums — "In Rock," "Machine Head," "Fireball," "Made in Japan" and "Who Do We Think We Are" — testified to the alchemical brilliance of what is still regarded as the “classic” Purple lineup. But personality clashes saw Gillan and Glover depart, and though David Coverdale led the group through two further LPs, "Burn" and "Stormbringer," by mid-decade, Blackmore was on his way out. GM: Did Purple achieve what you hoped? And, if not, what was the closest point they came to it? RB: I liked what we did on "Deep Purple In Rock" and on "Machine Head" and on what we did on "Burn," but I'm not so keen on the other stuff. There were several flashpoints that led to Blackmore's departure, but among them was Purple's rigid focus on self-composed material. Not since the early albums, when they covered such classics as “Hush” and “Help,” had the band acknowledged that they might benefit from bringing in other writers' material, and at the end of the day, that was the issue that pushed their guitarist over the edge. RB: One of the (issues) that led to me leaving Deep Purple was I wanted to cover a song by Quatermass (whose drummer) Mick Underwood was a school boy friend of mine. I played with him in the Outlaws as well. He played a song called "Black Sheep of the Family." I thought it would be a really good song for Deep Purple, but they weren't interested, so I did it with Ronnie Dio. Rainbow was born and, over the course of the next near-decade (and multiple lineup changes), Blackmore remained one of hard rock's most reliable exponents. A Deep Purple reunion followed, and a Rainbow revival, too. But his attentions were straying again, and this time far from anything that the bulk of his audience would recognize — even though he'd been talking about it, and playing tastes of it, all along. Blackmore's Night, formed with wife Candice Night, was dedicated to medieval music, and two decades on, the group is still going strong. And that despite the best efforts of at least a portion of his old headbanging audience. The last time Goldmine talked with Ritchie, he mentioned his dislike of larger venues where the fans who want to listen are outnumbered by those who just want to shout out for their favorite oldies. Was this an issue during the Purple and Rainbow days, or is it more something that has happened with Blackmore's Night? RB: It only happened when you're playing a quiet acoustic guitar part. In the early days I would make sure that my guitar was really loud so that no one would shout out anything. They wouldn't be able to be heard because of the loud electric. GM: Blackmore's Night has struck such a wonderful balance of self-composed material and covers; could you tell us what you and Candice look for in a song (your own or someone else's), before you tackle it? And how does that differ from your personal ideals in the past? RB: It's much more natural because we are living together — we are always around each other so if I have an idea or if she does we can play it right there and then to see if it has any potential. Whereas in the old days, everything revolved around rehearsals, which was a bit too regimented. GM: Your version of “Barbara Allen” (from Blackmore's Night's "Autumn Sky" album) in many ways brings us back to my earlier question about the folk clubs. Could you tell us how you first came to know the song ... was there any particular version you enjoyed, that made you think “we should do this?” Are you familiar with the Child Ballads collection from which it comes? And again, if so, tell us how that came about. RB: I first knew about that song from singing it in school when I was 11 or 12. I always thought it had a haunting melody, and I got Candy to hum the top line before she learned the song to see if it would suit her voice, which it did. It's one of the best songs we do on stage. She puts incredible feeling into the song. Very, very sad. The funny part of the song is it's written about a guy called William — and I have some very colorful friends. Where we live, some people would say "crazy people." And one is called William. His actual name is Bill From the Hill. Whenever she sings this very melancholy song, when it gets to the William part, we often look at each other and smile because we think of our crazy friend, William, whom I met in a tavern out at the end of Long Island. I was explaining a tune that Candy and I were about to play, that was written in the 1300s in Spain andBill From the Hill shouted from the end of the bar — "King Alfonse the Tenth!" He was correct, and I couldn't believe that someone had ever heard of King Alfonse. So he's been my friend ever since, but I digress once again. The first time I saw "Barbara Allen" was in a school song book. One of my favorite films is "Tom Brown's Schooldays," the 1940s version, and that song is being played in the background throughout the film. GM: Away from listening to music, do you read much about it? Is there, for example, a bound collection of 78 Quarterly or Sing Out on the Blackmore bookshelf that you take down and browse through?What were the last few non-rock books you read, or at least looked at and thought you'd like to read? RB: Musically, I'm always reading all the time. I am very inspired by reading about medieval and renaissance music, who played it, how it was played, what the instruments were. If I'm not reading about renaissance and medieval music, I read things about paranormal and psychic experiences. I also read a lot about American politics, and don't even get me started about that topic. I have very strong views about what is going on over here. GM: Finally, what's next for you? Is there a new Blackmore's Night album on the horizon? RB: Not yet — we took a year off. We just released one a few months ago called "All Our Yesterdays" that was No. 1 on the Billboard New Age charts. We will probably go back in the studio the end of the year. We have put out an awful lot of material the last almost 20 years the band has been in existence. At the moment I'm busy relearning all the old songs I used to play with Deep Purple and Rainbow for the three upcoming dates I'm doing with Rainbow. Then I tour with Blackmore's Night directly after that. And in between times, he's avoiding watching "The Ritchie Blackmore Story," which is a shame. He's missing a great show. Although he probably knows how most of it goes. © Dave Thompson, Goldmine Magazine - April 2016 |