|

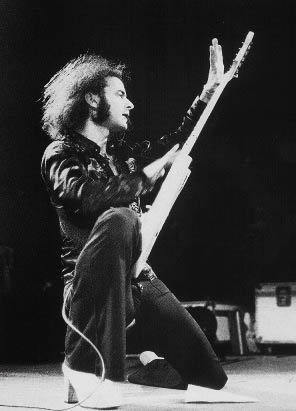

Ritchie Blackmore SPEED KING Ritchie Blackmore, hard rock's original shredder, looks back on his finest fretburning moments with Deep Purple and Rainbow.  Along with Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton and Peter Green, Ritchie Blackmore is one of the true gods of British rock guitar. The fierce vibrato, the sweet/biting Strat-through-Marshall tone, the sublimely savage blues-meets-classical licks are all trademarks of the much-copied Blackmore style (just ask Yngwie Malmsteen). All are much in evidence on Stranger in Us All, the latest offering from the man in black and his all-new, reconstituted Rainbow.

Along with Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton and Peter Green, Ritchie Blackmore is one of the true gods of British rock guitar. The fierce vibrato, the sweet/biting Strat-through-Marshall tone, the sublimely savage blues-meets-classical licks are all trademarks of the much-copied Blackmore style (just ask Yngwie Malmsteen). All are much in evidence on Stranger in Us All, the latest offering from the man in black and his all-new, reconstituted Rainbow.Though the faces are new -and against all reasonable expectations- the sound of the album is one hundred percent vintage Rainbow: melodic, majestic, metallic and positively medieval. But don't thank Ritchie for that, thank his latest titanium-lunged belter, Londoner Doogie White. "Initially I wanted to do more of a blues thing," says Blackmore. "But Doogie doesn't really have a bluesy voice. He's into the old classic hard rock, and he loves Ronnie Dio [Rainbow's original vocalist]. So as soon as he puts his vocal stamp down, its naturally curved more toward a hard-rock sound. And I thought, 'Okay, I'll go with that. There's nothing wrong with that. That's great.' " In truth, Blackmore didn't even want to call the new band (which came together shortly after his departure from Deep Purple last year) Rainbow. "I wanted to call it Moon, after my grandfather's surname," he says. "But the record company said, 'Oh no, no, no! It has to be called Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow for sales.' And I said, 'C'mon! I've done all that.' I really wanted to call it something new. But you know what record companies are like. So now Ritchie Blackmore has to call it Rainbow." Regarding his abrupt departure from Deep Purple, the seminal progressive/metal band with which he first established his reputation in the Seventies and later reformed in the Eighties, Blackmore doesn't mince words. "I left because of [Ian] Gillan. At the very least, a singer has a responsibility to people to kind of remember the lyrics and sing in tune. And I felt that he wasn't doing any of that. He didn't seem to have any remorse about it, either. It was like, 'I don't give a shit!' We were playing to packed houses in Europe. People were spending a lot of money to see the band. They would sing the words and the singer didn't even know what the words were. To me, that was ridiculous!" Along with his usual fiery electric work, the new album features a rare glimpse into another side of the Blackmore persona - the acoustic side. "It's taken me the last 25 years to get a grip on the acoustic guitar," he admits. "I was always hesitant about it. But now I can play it well." So well, in fact, that Blackmore is devoting an entire album to the acoustic guitar this fall. "It's sort of a renaissance, pop-folk acoustic thing," he says of the project, tentatively titled Medieval Moons and Gypsy Dances. "It's the type of stuff you can imagine people in Europe playing around a castle when the full moon's out. I'm quite excited about it because it's so different - there's not going to be any Marshalls." Marshalls, however, were much in evidence during the recording of many of Blackmore's classic tracks with Deep Purple and Rainbow. At a recent meeting with Guitar World, the Strat-lord took the opportunity to sound off about some of those prime-cut tracks. "HUSH" Deep Purple (Tetragrammaton, 1968) "IT WAS MY idea to do 'Hush,' a song by [session guitarist/solo artist] Joe South. I heard it in Hamburg, Germany. So I mentioned it to the band, and we did it. The whole thing was done in two takes. We did the whole album in 48 hours. "I liked the guitar solo-especially the feedback. That was done with my Gibson ES335, which I don't have anymore because my ex-wife stole it. I used that right up to the In Rock album, on 'Child In Time' and 'Flight of the Rat.' The reason I changed to a Stratocaster was because the sound had an edge to it that I really liked. But it was much harder to get used to. When you're playing a humbucking pickup, you've got that fat sound and it's quite forgiving. But when you play with Fender pickups, they're so thin and mean and edgy and hard. And every note counts; you can't fake a note." "APRIL" Deep Purple "I WAS BORN in that month. It was just a little throwaway tune I had. I brought it to Jon [Lord, Deep Purple's keyboardist], and he worked out the classical thing in the middle of it. I haven't heard it in 25 years. It was pretty adventurous for its time - especially in the key of A flat." Deep Purple/the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Malcolm Arnold Concerto for Group and Orchestra (Warner Bros, 1970) "I HAVE NO idea what to say about that. I never play it. I didn't even listen to the live record. It was something of a novelty. Trying to play with 25 violinists sitting next to you was not the greatest fun. I had my small Vox amplifier, and they were basically holding their ears and saying, 'Too loud!' So here I am trying to play to an audience, and I've got these violinists sticking their fingers in their ears. I felt like, 'Oh, yeah! Great! I'm feeling on top of the world here. Boy, this really inspires me to let go.' " "HARD LOVIN' MAN" Deep Purple In Rock (Warner Bros, 1970) "ONE OF THE engineers who originally worked on that album was this stuffy bloke who didn't like rock and roll music. While I was recording the solo on that song, I got this urge and started rubbing the guitar up and down the doorway of the control room to get all that wild guitar noise. So this bloke looks at me, and he's got this expression on his face as if I'd lost my mind. "Another time, we were listening to a playback, and I went, 'I can't quite hear the guitar.' And this guy's going 'Guitar? It's deafening. It's absolutely deafening! I can't take it. It's too loud.' And I'm going, 'Y'know, I can't hear it. I really can't hear it.' And this guy's going, 'You can't hear the guitar? It's fucking deafening, man. What's wrong with you?' And then Martin [Birch, engineer] goes, 'Oh, wait a minute.' And he pushes the fader, and the guitar had been completely off. So the guy went, 'Ooops!' And there he had me thinking it was me, that I had lost my senses or something." "CHILD IN TIME" Deep Purple In Rock "THAT RECORD WAS sort of a response to the one we did with the orchestra. I wanted to do a loud, hard-rock record. And I was thinking, 'This record better make it,' because I was afraid that if it didn't, we were going to be stuck playing with orchestras for the rest of our lives. "'Child In Time' is a great song. Ian Gillan was probably the only guy who could sing that. It was done in three stages, sort of like an operatic thing. That's him at his best. Nobody else would have attempted that, going up in octaves. "I think the guitar solo is relatively average. I did it in two or three takes. Back then, whenever it came to guitar solos, I was given about 15 minutes. In those days, that was enough for the guitar player. Paicey [Deep Purple drummer Ian Paice] would be there tapping his foot, looking at his watch going, 'How much longer?' And I'd be like, 'I've just got my sound together.' And he'd go, 'You going to be much longer?' "Sometimes on stage I would play it much faster than the record. I'd like it real fast, and Paicey would like it really fast. Only problem was coming into that part at the end of the guitar solo [hums part] that the band would do in unison. You can only play that so fast - unless you start tapping, which I don't do, out of principle. It's just an A minor arpeggio, but it's all downstrokes. You try and play that really fast after you've had ten scotches! That's hard to do." "SMOKE ON THE WATER" Machine Head (Warner Bros, 1972) "WE DID THAT track in a different place than the rest of Machine Head, which was recorded in the Grand Hotel in Montreaux. It was recorded in a big auditorium in Switzerland using the Rolling Stones' mobile studio, which was in a truck. For the backing track, we were going for a big, echoey sound. The police started knocking on the door. We knew it was the police, and we knew that they were going to say, 'Stop recording!' because they'd had complaints about the noise. So we wouldn't open the door to the police. We asked Martin [Birch], 'Is that the one?' And he said, 'I don't know. I've got to hear the whole thing all the way through to know if it's the one.' The police, who had a fleet of cars outside, kept hammering at the door. We didn't want to open up until we knew we had gotten the right take. Finally, we got it: 'No mistakes. That'll do.' After that the police said, 'You've got to stop. You've got to go somewhere else.'" "HIGHWAY STAR" Machine Head "I WORKED OUT the solo for that one before I actually recorded it, which I never used to do. I fancied putting a bit of Mozart over that chord progression, which itself is taken from Mozart." "LAZY" Machine Head "THAT'S A WEIRD solo because I did a particular part one day, and I did another part another day; you can hear the difference. I still criticize that solo. I think the song was great; the composition was good. But I could have done better. I was inspired to write that by Eric Clapton's 'Stepping out.'" "WOMAN FROM TOKYO" Who Do We Think We Are (Warner Bros, 1973) "I GOT THAT riff from Eric Clapton as well from 'Cat's Squirrel.' " "STRANGE KIND OF WOMAN" Made In Japan (Warner Bros, 1973) "WE GOT THAT whole call-and-response guitar thing from Edgar Winter's 'Tobacco Road.' He and Rick Derringer used to trade off on that, and we were into that band [Edgar Winter's White Trash] at the time. "I turned Ian Gillan on to Edgar Winter. 'Listen to this guy scream!, 'I said. And Ian's like, 'Who's that?' And I said, 'Edgar Winter Johnny Winter's brother.' And all of a sudden Ian started screaming [giggles]. That's where the scream at the end of the song comes from." "MAN ON THE SILVER MOUNTAIN" Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow (Polydor, 1975) "THAT WAS ONE of the first tunes I put together with Ronnie James Dio. One night during our last tour in Europe, I went on stage to do an encore. I meant to play 'Smoke On the Water,' but I started playing 'Man on the Silver Mountain.' And it wasn't until I was a little bit into the riff that I realized, 'That is not "Smoke On the Water." 'And I went, 'Fuck, what is the riff?' And I couldn't remember the riff. So I'm looking at the audience pretending, 'Well, I meant to play that.' And they're clapping, but they've got these puzzled expressions on their faces like, 'Why is he playing a song that he's already done in the set?' So I look over at Greg [Smith, Rainbow bassist], and ask, 'How the hell does "Smoke On the Water" go?' So he goes, 'Duh, duh, duh, da, duh, da, duh.' So I finally went into that." "CATCH THE RAINBOW" Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow "THIS WAS INSPIRED by Hendrix's 'Little Wing.' We used to go on for 20 minutes live with it, and I would play an elongated solo. "I remember one really long solo way back in '67, when I was living in Hamburg, Germany. I was into Indian music at the time and playing Indian scales. I got up with this band to jam in this packed club once and played all those chromatic, weird Indian scales. I was really, really getting into it - playing, playing, playing. And I thought to myself, 'This is great. This drone is really working.' At the end of the song, I looked up, and all the audience had gone [laughs]. I expected to hear rapturous applause, but I had driven everybody out with those Indian scales. So I'm very wary now of playing long solos because I'm afraid of driving the audience out of the room." "BLACK MASQUERADE" Stranger In Us All (Fuel Records, 1996) "I ALWAYS FELT that 'Anya' [from Deep Purple's The Battle Rages On, 1993] was ruined by Gillan's singing. This is my way of doing 'Anya' again with a proper singer. "I played acoustic guitar on that track, which is kind of a first for me, and that posed a unique problem when it came to recording that solo. When I play, I hum along - I sing the notes as I'm playing. We got that particular solo down on the first take. Pat [Regan, producer] was really pleased with it, and I thought, 'Great! We did it in the first take.' Then he played it back and said, 'What's that noise in the background? Are you singing?' So we had to keep going over it. And I couldn't play without humming it. Finally, they had to mike it in such a way that the mic wouldn't pick up my humming while I was playing." "ARIEL" Stranger In Us All "WHEN WE WERE recording that, we thought we'd put some acoustic chords at certain points you'd hear an acoustic for like two seconds, then it would drop out. And the rest of the time, I was fiddling around, trying to remember what the next chord was because I hadn't played the song in a while. You can hear me saying, 'Dink, dink, dink, bum, bum, bum what's the note? Oh yeah. Right!' Just fiddling. When I heard the first mix, all this rubbish that I was fiddling with was actually on there. I went, 'Uh, Pat, there seems to be some strange guitar playing on here.' He said, 'I kind of liked it. I thought it was real, man.' And I'm like, 'I think we've got to get rid of that.' "I was trying to find the right note because I had forgotten what key I was in. I had originally written that song in the key of A minor, and had transposed it to E minor for Doogie. So mentally I'm going, 'Are these all the chords to the song? What's the next chord?' I'm hitting all these wrong chords on the acoustic guitar. And he brought all that stuff out. I think he was very tired at the time." Mordechai Kleidermacher, Guitar World, December 1996 |