|

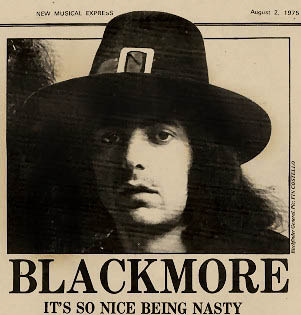

Ritchie Blackmore IT'S SO NICE BEING NASTY They were Deep. And very, very Purple. And very, very, very rich. Then somebody left. Then somebody else left. Finally RITCHIE BLACKMORE left. Now there's only two originals left. The whole thing is, - can DAVID COVERDALE be said to be on a good screw and has the Bitchfinder General got the whole world sussed out? PETE ERSKINE (in London) and CHARLES VERGETTE (in California) report. HE'S ALRIGHT," says the PR reassuringly on the other end of the 'phone. "He's not the character people make him out to be." The Holiday Inn, Swiss Cottage. Strictly nouveauland. Restrained vacuum-formed decor and static electricity shocks from the toilet door knobs. The ashtrays in the bar are bland enough to discourage even the most hardened pilferer. Instead I fill my pockets with book matches, lie to the barman that I'm a guest, and pay 40p for an expensive looking bottle containing very cheaply produced beer.  A tall, lank-haired gentleman in jeans and Spanish-copies-of-western-boots enters, buys himself a drink and introduces himself as Ian Ferguson, Ritchie Blackmore's road manager. Well, tell us then, Ian, what's he really like... I mean, you know, working for him 'n' all?

A tall, lank-haired gentleman in jeans and Spanish-copies-of-western-boots enters, buys himself a drink and introduces himself as Ian Ferguson, Ritchie Blackmore's road manager. Well, tell us then, Ian, what's he really like... I mean, you know, working for him 'n' all?"He's very honest," says Ferguson, in what might be a Scottish accent, "... and very outspoken. But he never orders me to do anything. He always asks." Nevertheless, Ferguson adds, Ritchie always gets his own way. Which might explain why he's half an hour late for this interview - he's gone shopping. Presumably for clothes - he makes his subsequent entrance in a Tesco tank-top ensemble which makes the lead guitarist of the Doobie Bros look sharper than Peter Wyngarde. Presumably to gain some kind of psychological tactical advantage, Blackmore proffers a handshake from behind the settee so that I have to stand up, twist round and lose my equilibrium all in one swift fluid movement. His companion, a short personable American guy with a thick bush of black hair and Italianate features, invites him to sit next to me and we begin - with Blackmore morosely explaining that the reason he's doing interviews is that a few "thick people" don't know that he's left Deep Purple. He stares with an expression of acute boredom straight through my notepad and through the glass sliding doors bordering the hotel pool which is filled to capacity with the children of visiting Americans. Blackmore and Purple parted company three months ago. "-Physically that is. Spiritually, I left about a year ago," he adds dryly. One gathers you didn't enjoy playing on the last album. "I made the best of it. I was a bit tired of the ideas and the personnel; it was all a bit routine." He does not think that the band's approach is "dated". "But everybody's approaching their material in the same way. Most of the big bands I know are; most of them are very lazy. "The way we used to approach making records was we would allot two weeks for rehearsals, then for maybe twelve days play football, and the other day we'd sleep, then we'd probably rehearse for one hour of the day that was left. "We wrote most of the material in the studio, so it was a case of falling back on professionalism rather than creative... um... songs. You mean you were just going through the motions, Ritchie? "Yes," he continues, staring toad-like into his beer, "I lost the excitement of it." Hard to imagine Blackmore excited. But wait... "...But now I've gained it through being with different personnel." And he's certainly not into the solo LP business, this is just another band. The band comprises Jimmy Bain, bass, Gary Driscoll, drums, the Italianate American (Ronnie Dio) lead vocals, Micky Lee Soule, keyboards, and Ritchie Blackmore, guitar. Blackmore ploughs on resignedly, still gazing glazedly at the aquatic activity through the glass doors. "People used to say to me, 'When are you making a solo?' and I used to say, 'Well, I do that all the time with Deep Purple!' It was a case of I wanted to use different people and make just try and make... I found that quite honestly I was doing most of the work with Deep Purple myself - without sounding conceited - I just found that a lot was relying on me. So I thought, sod this..." In terms of what? The stage performances? "No. The writing." Oh. I thought most of that came from Jon Lord. "Hmm, I know," he smirks. "A lot of people thought that." Has it always been like that? "Yes, since 'Deep Purple In Rock'. Before that it was kind of equally shared. Since 'Deep Purple In Rock' it was written always by Roger (Glover), Ian (Paice) and myself. John would be very good at advising whether to use an A Major or a C Minor but he didn't write. That's another big reason why I left. There were no writers in the band - including myself I can write to a degree but I do need help. Ian was always there - Ian Paice the drummer - he always had lots of adrenalin, wanted to get on with it and play - but a drummer can't contribute any more than playing the drums unless he's a songwriter and a piano player." "There were people who said we hated each other," he observes, shifting his gaze to an adjacent lavatory door, "but I never let it get that far. Otherwise we'd have broken up a long time ago. I used to have my own dressing room because I like solitude before going onstage; I have four or five guitars to tune up and I can't do that with someone playing bass or organ in the same room. I prefer to be on my own. I'm a loner - not because I don't like people, it's just that I like to be alone because... uh... for instance... I find myself more interesting than most people I meet... It sounds pretty conceited... probably is... I dunno." And he chuckles to himself, then leans across to Dio attracting his attention by grabbing his knee, halting me in mid-question by pointing out to Dio how amusing he finds the perambulations of one particularly graceless non-swimmer. Blackmore, his mirth subsided, continues: "We did have a channel we had to keep to - or producing hard rock all the time. I love hard rock. It was my idea to do it, along with Ian and Roger, but we couldn't stray from it very much or people would go 'It's not as hard as their last one' or if we did do a hard rock thing the press would always go 'Huh, same old thing. Heavy Metal Rubbish'. Which they never," he adds wearily, "saw the subtleties of. And of which," he post-scripts slightly petulantly, "they never will do. They'd rather talk about folk singers. But that's another thing." About what? (Sorry). "About folk singers. They turn out second rate music but it's quiet and they can talk over that." INTERESTING, THAT. "A folk singer is someone who turns out second rate music." Blackmore has a curious fixation with "folk singers" - as if there're only two types of music in the world: Deep Purple and folk singers. He's a real dab hand at the lightning epithet, too. Last April he told an interviewer: "The socalled greats like Segovia knew nothing about feedback." Here he was making a correct assumption. "The music that we make demands attention," Blackmore continues, retracing earlier steps, "which puts people off. The best writer, I find... is Chris Welch... It's the same as... Black Sabbath. Immediately you say their name people say 'Oh, rubbish, rubbish' - they might not be the best in the world but they're certainly a lot better than most of the folk singers that get talked about and praised." Give us an example of a "folk singer". "I can't. I really don't know because I don't take any notice of them." Blackmore prefers Jethro Tull and J.S. Bach. Do you think that people missed the subtleties in Deep Purple, Ritchie? "Yes. I think they do. I think they did at the time. The kids didn't, the press did. That's why the band was..." What were the subtleties? "The subtleties were what was involved in the simple structure of the song, incorporating such a limiting structure. To have to make up good solos in that structure is very hard. People would hear a riff and say 'Oh, that's kids' stuff' but it's not as simple as that. And you can name music in seven-four or five-four but it's easier than making four-four if it's not different, the content. For instance, the solos count on a lot of the songs. "That," he concludes, "was the subtlety of most of the songs." But isn't that approach of The All Important Solo a bit passe? I inquire, and he stares blankly and lets me ramble on until I trip over my own point of view but finally manage to wind up by saying that that particular approach has been used for at least ten years. "And it'll probably go on being used for the next hundred years," he responds sullenly. But ain't it a little predictable? "No. I don't think so." Well, Clapton, for one, forsook it ages ago. "Yeah. And he's also got very boring," comes the quick rejoinder. So you're still a solos man, Ritchie? "No, I'm a backup man now. I play cello," he says cracking a joke. "I back up Ronnie who's on violin." They both laugh goodnaturedly. He's played guitar for 19 years and doesn't listen to many other guitarists, mainly violinists and cellists. He doesn't listen to much heavy rock, goes to quite a few classical concerts. He says he believes heavy rock is very closely related to J.S. Bach in terms of rhythms and directness. In my opinion, that is. Not that anyone else would think so. They'd say 'How dare he say that!' "I either listen to Bach or hard rock done by a very good band. Not too many good hard rock bands about... Paul Rodgers is a good singer but Bad Company are pretty average. Zeppelin sometimes pull out something good... One wonders - as a layman, that is - just what it's really like to be a famous lead guitarist. Would Ritchie like to stow the image for awhile? "I don't think about it. But I wouldn't like to get shot of it. Not at the moment. I still like the adrenalin and the respect you can get, the power... but only in certain ways... I don't like the power of when somebody asks me for my opinion on something because often my opinions go from my subconscious to my unconscious and they don't really make a lot of sense to people unless they know my music inside out." Notice the inference? He's right. I do not possess a single Deep Purple recording. "... And," he continues considerately, "it's sometimes confusing for a person to hear me talk unless I'm in the right frame of mind to talk about what I'm saying - which is nothing. I'll stop talking." Pretty snakey, Ritchie, pretty snakey. A quick sidestep with an inquiry as to who's in his new band, Rainbow (I already told you that), so we'll pass on to the knowledge that Dio gets pissed off when reporters neglect to announce his full name - i.e. the "James" in the middle. Ronnie James Dio. Alright? Blackmore makes another joke. Whilst spelling out the names of his band he says "Jimmy - as in George Harrison - Bain". And we all laugh good-naturedly and stare at the pool. Dio is a nice guy. "It may seem odd," he observes, "to be doing the Rainbow thing after being a goodtime rock 'n' roll band." Dio and Ritchie write together. I mention that I heard some of it the other night on John Peel's grog. Blackmore immediately interjects. "Best forgotten, that," he grumbles. Why's that? "Well. He split the soundtrack up about seven times so everything sounded completely out of context to what we were saying..." Dio tells him that Peel, in confidence, has been praising Blackmore to him. "Oh well," says Blackmore, visibly lightening, "let him carry on then. "No," he continues, more reasonably, "somebody made a bit of a mess-up of equalising the tapes from speech to music. No, John Peel," says Blackmore, steadying himself for yet another joke, and turning to Dio, "no, John Peel's a fantastic guy," rounding off with a mysterioso belly-laugh implying that - yet again - he's got it all sussed. What a temporal colossus this man is! Superficially Rainbow is not a million miles removed from Deep Purple. I ask Richie where he thinks the difference lies. "There's more excitement, there's more enthusiasm because we're all new - I like Ronnie's voice very much, I like the way he can interpret what I play on the guitar - he seems to be able to integrate his melodies into my guitar progressions." You were saying something on the radio about it being "medieval". "Yes, we do use a lot of medieval modes." Like your "Witchfinder General" hat? (I didn't actually say that. I only just thought of it. Traditionally Blackmore has often worn a Cromwellian stovepipe hat with a buckleband onstage.) "... Uh... in the way that the modes work slightly differently to the scales. You use a lot of notes, whole tones one prime example being 'Greensleeves' which was written in the 16th century by Henry VIII - or so he told me - or rather it was probably written by one of his court minstrels who he beheaded and stole the publishing rights from... Dio chuckles. "Anyway. One of the songs we do is called '16th Century Greensleeves' which is how we imagined the story to be." It's a period that really interests Ritchie. "All the music I play at home is either German baroque music - people like Bauxteheuder, Telemann, or it's medieval music. English medieval music. I prefer things like the harpsichord, the recorder and the tambourine. They used very weird instruments in those days..." then, breaking off, to Dio (Blackmore is still surveying the pool), "She's drowning... and breaks up laughing. "And I'm interested in the supernatural and psychic research..." then breaks off again, "She's really a great swimmer..." and he and Dio crack up again. Dio then gets up, and perhaps by way of recompense, buys another round of beers. "Whenever I'm pissed off with the rock scene," he concludes, "which is quite often, I just tune in to Bach, play my Bach records and medieval music and people come round - like other artists - and it's so funny, the reaction that you get. They think 'Ah, rock musician, gold records on the wall', expecting all the funk shit to come booming out - shoeshine music - and on comes medieval tambourine dancers and jigs... and Bach!" And folk singers? Pete Erskine, New Musical Express, August 2, 1975 Deep Purple BOLIN'S ZIP GUN DOES THE TRICK  "DAVID COVERDALE? No, never heard of him, I'm afraid," says the Bob Haldeman lookalike, coming over from washing his car. "Are you sure you've got the address right? You might try down there," he adds having to raise his voice over the sound of the thundering Pacific surf.

"DAVID COVERDALE? No, never heard of him, I'm afraid," says the Bob Haldeman lookalike, coming over from washing his car. "Are you sure you've got the address right? You might try down there," he adds having to raise his voice over the sound of the thundering Pacific surf."He's in a rock `n' roll band, Deep Purple." "Oh yeah," comes Haldeman's reply, his eyes flickering in recognition. "It's down there alright, I've heard a rumour that there's somebody down there like that." We finally locate the premises, right next door to PlumMouth. Thanks, man. Coverdale sneaks his head round the door. "You didn't tell anybody else "where the place is, did you?" he asks worriedly. We didn't. "I spend most of my time down here nowadays. I don't like to go out much. You either go to a place that won't let you in unless you're wearing clothes to suit them or you go somewhere where people recognise you, come over and start laying down all sorts of shit on you about this and that," says Coverdale as he leads through the kitchen into the living room. It's very chic: white furniture, white carpet, white walls, white table, white kitchen. Only a stack of records and the regular battery of tape recorders, amplifiers and a turntable betray the feeling that the place is best suited for a 40-year-old member of the nouveau riche. Purple's new guitarist, Tommy Bolin, walks in, his multicoloured hair glowing. It looked far more radiant in the afternoon sun than it had at the previous night's lacklustre Bad Company show at the Forum where we'd first met. How time flies. It's nearly two years since Coverdale picked up his last boutique pay check before taking over Ian Gillan's position as Purple's lemon-squeezer extraordinaire. Now Bolin's the new boy with just three weeks of Purple membership behind him. A month ago the former James Gang/Billy Cobham axeman was sitting on his butt searching out a gig. Today he's in the hot seat, having taken over the spot vacated by Purple's founder, that doomy, dark and moody King of Heavy Metal Guitar, Ritchie Blackmore. After a couple of hours drinking and enjoying the more exotic fruits of rock 'n' roll success, the mood is hardly conduscive to serious conversation, but we try. Seems that Coverdale and I will make it, but Bolin is a little further out into the cosmos. "Ritchie was worried about the direction he thought the band might be headed in," opens Coverdale, getting straight to the cause of Blackmore's departure, a move many had expected for months. "He didn't like the soul that was creeping into the band. See, what Ritchie regards as funk are things like "Sail Away" and "Mistreated" and that's the direction the rest of us saw the band headed in." Indeed, those two numbers, the bouncy "Hold On" and the haunting acoustic "Soldier of Fortune" on "Stormbringer" all marked changes for Purple, changes that the strongwilled Blackmore found hard to tolerate. (See the above feature). It was undoubtedly the introduction of bassist Glenn Hughes and Coverdale himself in 1973 that caused the marked realignment in Purple's appproach. First came "Burn" which saw a hint of the band's infamous zomboid inhumanity being eaten away in favour of a more earthy approach. The pattern was exaggerated by months on the road to prove the worth of the new-look outfit. As confidences grew, Blackmore's strangle hold over the band began to weaken. Them came "Stormbringer", a surprise to many die-hard Purple-haters. It served as consummation of the redirection its predecessor had pioneered. In essence, Blackmore's guitar no longer held the rest of the band at gun-point. Glenn Hughes' bass had created a far stronger rhythm section with Jon Lord's organ and Ian Paice's drums. Not only stronger musically, but stronger mentally. The Blackmore regime was over. "Sure," Coverdale agrees, between sips of white wine. "He was worried that the next album would be even more bassoriententated. He wanted to go out and get the things he really wanted to do, the guitar things, out of his system so that he could get into being a fifth of Deep Purple without feeling compromised. So he went out and decided to do his solo album." Yet it's hard to imagine Blackmore,ego and all, wanting to return to Purple if his solo venture worked. Once he saw new influences coming into the band that he didn't like, and saw himself outvoted by the others, there was no way he could stay. "Yeah, a lot of the songs on his album were ones that we all rejected for 'Stormbringer'," Coverdale concedes again, yet still adamantly refusing to say anything derogatory about his former boss. "He put forward a lot of ideas he knew we wouldn't be interested in." Rumours started flying, each one adamantly denied by Purple management - who seemed to take any suggestion that Blackmore might split as a personal insult. The reason for the denials, says Purple manager Rob Cooksey, was that Blackmore had not yet decided to quit. However when Rolling Stone quoted Blackmore as saying he considered "Stormbringer" a "load of shit" it seemed the end was nigh. "Ritchie never said that," insists Blackmore's mouth-piece, Cooksey. "It was a terrible piece of misquoting. The writer didn't even put his name on the piece. Ritchie was really upset about it, especially because of what the other guys in the band must have thought." Sure. "We started the last European tour with Ritchie still a full member," says Coverdale, explaining the final split. "After we'd done a couple of dates I began to feel strange vibes and knew something was going on. I went to see Rob Cooksey and I could just tell from his eyes that he was keeping something from me. I could sense that he didn't want to commit himself because Ritchie had told him something in private and he didn't want to break that confidence, even though it concerned us all business-wise." It finally transpired that Blackmore had finally reached the point of quitting. "Now he can do exactly what he wants. I think he'll be happier now: he's got much more control with the people he's working with. Instead of turning round to Jon and telling him what to play and Jon saying 'I prefer it this way', he's got players who'll do exactly what he tells them to," says Coverdale adjusting his glasses, adding, "They're good players too." The singer's immediate reaction was to get on the phone and begin organising his own band. True to his soul roots, he a got a, horn section and chick back-up singers together first. "Then I suddely realised I was calling Jon to play organ, Ian to play drums, and Glenn to play bass, so I thought, 'what's the point of doing it solo, why not U keep the band together'?" WITH BLACKMORE, the founding member, now joining the ranks of Purple refugees, some suggest the band should break up or at least change the name. Coverdale gets very defensive about such talk. Very defensive indeed. "We still own, the name Deep Purple, as far as people and musicians. We decided to keep it going because we wanted to keep working together, nothing else. We can keep it going without Ritchie. I think Glenn and I proved the band could keep going and maintain its validity with new members," he says, getting edgey. Ooops, sorry David. Anyhow, having decided to keep it together, the first priority was to locate a new guitar player. Problem. Love him or hate him, Blackmore is a very distinctive player; those spinesearing, ear-bending riffs don't come easy and though thousands-tried to copy him, nobody got close. Each member drew up his own list of choices and the names were pooled. Jeff Beck topped the popularity polls but, as Coverdale put it so succinctly, "He's very much his own man and it would have been like taking on..." An even more determined Blackmore? "Exactly, excellent! He's very individual. It's generally accepted that he'll form a new band every month, go on the road or record an album, then disband it. It's Jeff Beck and whoever else is with him is incidental." Next choice was Clem Clempson who was flown over from England to audition. He failed. "I think he's suffered through his associations with Steve Marriott in Humble Pie. He's just been a bandsman for too long, like a hom player with Duke Ellington's band. He didn't have the magic that we needed to inspire us all. You gotta remember man, that to replace Ritchie... well, you know. He wasn't just anybody and you can't get just anybody to replace him." Next in line to the throne was Bolin, an undisputed punk. "I got on the phone to our agent in New York to find him because I thought he was an East Coaster and he told me Tommy was living just five miles away from me in Malibu. The management were a bit scared when they heard he's played with Cobham: they thought, ... 'Oh no, a jazzman'. But I called him up when we were both really stoned and we talked for half an hour about curry and chips and finally invited him down to a session." At the mention of his own name and getting stoned Bolin comes to life, brushing his peacock hair from his dilated pupils. The former replacement for Joe Walsh in the James Gang, then guest guitarist on Billy Cobham's excellent Spectrum, Bolin tried to speak; "Uh I'd been up all night... like... and I... er... wanted to call it off... but when we started playing..." "He kept apologising," interrups Coverdale with a grin. "Saying 'I'm sorry, really sorry, I haven't played in ages' and I was just standing there going 'Jesus Christ, there's this phenomenal sound coming out, he hasn't got his right guitar and hasn't practiced in months'." Bolin joined Deep Purple. "Blackmore put a good word in for me, didn't he," he asks rhetorically. "No, nobody said anything," says Coverdale, slightly taken aback. "You liar Blackmore... you lying... Charles Vergette, New Musical Express, August 2, 1975 |