|

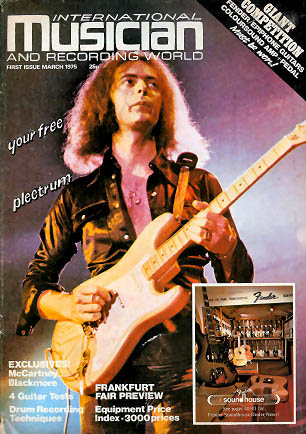

Ritchie Blackmore "American guitarists all seem to sound the same" Ritchie Blackmore, perhaps the world's finest electric guitar player, does not take well to interviews; he prefers to do no more than two a year. Being the lead guitarist in the world's most successful rock 'n' roll band, Deep Purple, doesn't allow him much time to worry about his public image. Besides, Ritchie's own choice is to do interviews only when he's talking about music, protesting "I'm a musician, not a politician, and I don't want to influence the minds of our fans." I recently had the privilege of talking with Ritchie Blackmore about the guitar, and his music.  JT: When did you actually begin to play guitar?

JT: When did you actually begin to play guitar?RB: I started when I was 11, I got my first guitar, a Framus Spanish. I made it into an electric with thousands of pickups - each birthday I'd get a pickup, so when I was 15 I had about five pickups on it. I built it myself, as I was very interested in electronics and things, I worked in the aircraft industry when I left school at the age of 15, on-aircraft radio. That helps, because for the past ten years the guitar has been an electric instrument - amplifiers and all that - and it helps to know a little bit about electronics, feedback, whatever. JT: You say you quit school when you were 15 - was that to join a rock 'n' roll band? RB: I was in a skiffle band when I was 13. I started classical for about one year, just to get off on the right footing music-wise. After that, it got a bit tedious and I wanted to play rock, and I couldn't keep up with the classical playing - it was a bit stiff and I played everything by ear. I think its very important when you first learn an instrument to go straight into the training of it, or whatever, to get things right, because once you start picking up bad habits you'll be stuck with them forever. It's like driving, you must learn properly from the beginning and then adapt to your own style. I learned to use all my fingers, while most blues guitarists only use three. I developed a name for playing very fast runs, but to me it wasn't fast, it's just that I've learned to use my little finger. I play very easily with it, whereas these other guys would be jumping about because they'd got into the bad habit of their third finger being the most important and the little finger never came into it. Obviously this is very important. JT: Did you get your first real performing experience with Lord Sutch? RB: Yes it was Sutch, although I had my first professional band in 1960, just a band from the area but we did a lot of travelling around. I went with Sutch for about a year, and I learned a hell of a lot from playing with him. I was about 17. He taught me a lot about showmanship; before then, I used to play in the wings, very shy, whereas when you play with Sutch, you either play out front or he'll pull you out, literally. He'd get hold of my guitar and pull me out front, rocking me backwards and forwards to get me to move, saying "C'mon, get your finger out - get going". I was panic-stricken. After that, I saw that coming on that way worked, that's what an audience wants. Guitar playing is enough 90 percent of the time, but they want something to hit them in the face a little bit. Even with myself when I go to see another guitarist, if he just sits down and plays I do tend to go "ugh - do something!" Someone like Albert Lee or Big Jim Sullivan. Big Jim Sullivan was a teacher of mine 'cause he used to live around the corner so I could go to him a lot, they're probably the best two guitarists in England. Nobody knows it because they don't have any novelty side-effects, they just play. It's hard to compete with Albert Lee. JT: Aside from the fact that you use your little pinky, you've also got a lot of speed in your right hand. RB: That's the hardest part, the right hand. I often used to do exercises without playing with my left hand at all, jumping from one string to another. Not just jumping to any string, obviously, but jumping from the sixth to the fourth, the fifth to the third, the fourth to the second, third to the first - you'd be surprised at how hard that is to do fast, jumping, and that's half the technique. When you go to classical lessons you're taught how to up and down stroke, and that's very important. Somebody like Alvin Lee plays the difficult way, he picks it all on the downstroke because obviously when he first started he didn't learn the upstroke and it makes it so much easier. You can only go so fast that way - what he plays, he plays very well because he's playing it the most difficult way I could imagine. Some of his stuff's good. Like Wes Montgomery, he played with his thumb. It does add another dimension if you learn to play in an unorthodox manner, you get a different fingering, which I suppose helps. If everybody played in the same way, it would sound a bit too samey. JT: Like when a left-handed person learns to play guitar righthanded. RB: That one really throws me, I don't know how they do it. I guess it all gives you a different perspective on the instrument. I'm learning cello now, I've only been at it a month now but it's coming along. Vibrato is totally different, you have to have it on the cello because you're searching for the note within reason. You're within a sixteenth of an inch and your ear is going for the note, if you straight away try to hit away without the vibrato, it sounds awful, you will not get the right note. It's got no frets, you have to feel your way to the note by vibrato. The bow is also very hard because it cramps your hand. JT: Do you play any other instruments, like for instance bass guitar? RB: I often play bass, I was recently jamming with Alex Harvey on bass. I like to play a lead bass, because I can play it as fast as I play guitar. A lot of people find this difficult, and I don't know why because it's no more difficult to play the bass as fast as a guitar. What annoys me is that a bass is often an excuse for playing second guitar. The guy says "I wanna be in a band. I can't play lead very well so I'll play bass". They don't really look at it as a separate instrument, not in the way that Ray Brown or Charlie Mingus looks at it - that's when you're talking about bass players. I saw Charlie Mingus in France and he was incredible. Glenn is funk-mad [Glenn Hughes, Purple's bassist]. He loves that sort of music. He's a very talented bass player, he never ever practices but he's got so much feel. He never plays the obvious, often I don't know what he's playing - many bass players would just go "Dum, dom,dum, dons' but Glenn will go "badum-baddle-um". His timing is such that he can't play anything straight, but he's really good. JT: What guitarists do you like? RB: I like Jeff [Beck]. He's my favourite guitarists. There are a lot of guitarists around that get overlooked. When you're a guitarist yourself you tend to get so buried in what you're doing. Mike Bloomfield is really good. Steve Howe's always been a very good guitarist. I'm not too struck on Jimmy Page and Eric Clapton, I never saw what was in Clapton at all. He's a good singer. JT: How do you view someone like Peter Townshend? RB: He's part of "the Establishment" .... you can knock the Establishment but there's not much point. There were days in `64 when he inspired me, because he was the first one ever to use distortion, it was unheard of in those days, and he did a distortion solo in "Anyway Anyhow Anywhere". That was really good, I thought The Who were great when they first came out. Townshend is not so much of a guitarist as an all-round guywriter, all that. There are so many people who are good guitarists who aren't even names. JT: Are there any American guitarists that you find worthwhile? RB: Tommy Bolin, especially. There's a guy in a group called Stray Dog, and I was slightly listening to him outside the Record Plant door when he was recording, and he sounded great .... I don't know who he is. The only criticism I have of American guitarists is that they all seem to sound the same when they play rock, they've got this fuzz sound, I don't khow whether it's their amplifiers or not. They could be brilliant, but they don't seem to care too much about their sound, for some reason. When they go into the treble side - I know it may be a fault with American amplifiers, because I've used them myself - they grate a lot. As soon as they go off in the high register they start giving this false distortion that's built into the amplifiers. Every amplifier sold on the American market seems to build in this effect, where as soon as you go up in the high register they built in a bit of distortion, and it shows. It sounds like the speaker's about to disintegrate, it's a weird sound but you always know it's an American amp. You get a lot of fret noise and string noise when you get up at the top, sounds like the amp is trying too hard. You can't beat a souped-up Marshall. Beck doesn't have a Marshall. I don't know what he uses but his amps are very good. He's got the best guitar sound I've heard, he gets such a good clean sound. Being a guitarist, I obviously know a lot of tricks of the trade, but whenever I watch Beck I think "How the hell is he doing that?" Echoes suddenly come from no-where; he can play a very quiet passage with no sustain and in the next second suddenly race up the fingerboard with all this sustain coming out. He seems to have sustain completely at his fingertips, yet he doesn't have it all the time, only when he wants it.  JT: He manages to get crystal clear harmonics out of the guitar that I didn't even know were possible.

JT: He manages to get crystal clear harmonics out of the guitar that I didn't even know were possible.RB: Jeff's a very natural guitar player. I think he's more interested in building cars though, he's a very good mechanic. He builds them himself, I don't know how many he's got by this time - he's just finished one, and that's what inspires him to play. After you've been playing a certain amount of time, it's nice to be able to think about the guitar, and I know he does by the choice of notes he plays. Some guitarists only play what their hands want to play, they don't play what the head wants to play. After you've been playing for about eight years, you start to think more about each note, contemplating a solo about a quarter of an hour beforehand. You think "what kind of thing would go along with this" without even touching the guitar, that's what it's all about. You have it in your head, and then it's on to the guitar if you can do it. It's hard, but that's the most rewarding thing, to go straight from the head to the guitar without the business of "this sounds pretty good" or "I'll throw this lick in". Your head should tell your hands where to go, the hands shouldn't do it all by themselves. Hendrix's head must have been very good, I'd say, from listening to his music, because he never repeated himself. That means his hands weren't having the say, he was saying "I want to play this". A lot of guitarists who play very fast play a blur of passages that they've learned for years which impress the guy who doesn't know anything about music, cause they go "He's good isn't he - listen to that, he's very fast". A real musician knows that it isn't merely speed, but the choice of notes, that's what it's all about. If you were to ask me what's the difference between him and him, it's often what they leave out - not what they put in. JT: How much preparation do you put into a solo before you step into a studio, do you have things pretty much figured out or do you walk in blind to what you're going to play? RB: Everything is done spontaneously. JT: Even something like the solo in "Highway Star?" RB: Yes, it has to be because I'm just hopeless at working things out. That solo got put down and then I listened to it and then I had to copy it, because I played it in thirds, I think. That's hard, to copy your own solo, that part that moves in thirds is an old run I used to play ten years ago. Johnny Burnette, the guitarist who used to play with Elvis Presley and introduced me to James Burton (who used to play with Rick Nelson and is now with Elvis), came to England; he taught me that particular run and I hadn't used it for years. It isn't entirely original, but it's exciting, that's the main thing. JT: That's the type of solo that if a copy band learns the song, they can't do it without learning the solo. RB: If you play very simple, exciting songs with riffs in them you can throw in all kinds of subtleties, the solos can be more complex, they aren't just silly soloes. Yet people listen to the first two bars of a Deep Purple and say "It's very simple and heavy punk rock" and that's the end of it, those people don't really bother us .... they don't buy our records. They don't buy any records, they get them given to them .... it's a shame. JT: I'm no believer in punk-rock or heavy metal-rock myself, it's all rock, it's all music and it doesn't much matter what you call it. RB: Yes it is, you're right, but there are people around that give rock 'n' roll a bad name. I listen to the radio and sometimes hear things that are just awful. When you travel and you've been in the business so long, you have an awareness of certain people's aura and how they are as people and what they mean. I tend to analyse a person in a couple of seconds and say to myself, "I don't want to talk to him because I think he's a very boring person". So I give them the cold shoulder, and they look at me and see I'm very serious and cold, and they leave me alone. It makes me very happy, really, because I don't want to talk to those people. 80 percent of the people I meet are very boring people, and consequently I don't meet them. I have my own dressing room and keep myself to myself. My friends come in, people who are nice and polite come in, whereas the bilge that you get in some dressing rooms - I sometimes go in our main dressing room and there can be 100, 200 people there and they're all freeloaders, talking nonsense and drinking this and that. I couldn't handle that, when the band members actually have to go into the toilet stalls to change so I'm content to watch the other bands and maybe meditate a little before the show. It's very important to watch the other bands, .... I don't believe in the showbiz thing of turning up at the last minute, "the Big Boys are Here, the Stars of the Show". I think it's all a laugh, the whole business end of making music. © Jon Tiven, International Musician and Recording World, March 1975 |