|

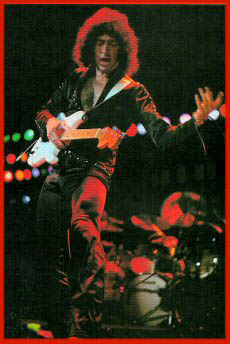

Ritchie Blackmore THE GUITAR GREATS  One reason for the selection of ace heavy metal guitarist Ritchie Blackmore as one of our subjects relates to a previous, slimmer and somewhat inferior volume on guitarists, which was written some years ago by John Tobler in which the choice of the players was not his.

One reason for the selection of ace heavy metal guitarist Ritchie Blackmore as one of our subjects relates to a previous, slimmer and somewhat inferior volume on guitarists, which was written some years ago by John Tobler in which the choice of the players was not his.Little or no correspondence ensued following the book's publication, the only letters received all being from puzzled readers enquiring how it was that Ritchie Blackmore had been omitted. During the ensuing years, Ritchie's standing has become substantially greater and now records by his band, Rainbow, are guaranteed huge sellers, while tickets for his rare British concerts are oversubscribed at great speed. Aside from that, he possesses the ultimate qualification for inclusion - he is undeniably a great guitarist. Blackmore was born on 14 April 1945, in Weston-super-Mare - no, it was 1950! (laughs) - and his first memory of a guitar came, as he puts it, "at the stage of puberty. Maybe it was because it was like a woman in shape, so I loved it. It was an acoustic 6-string guitar, and I became interested in the gloss and the sheen and the way it was made. It was a very fine instrument, and I wanted to play it. So I persuaded my father to buy a guitar for me which cost seven guineas, and it went from there - he said that if I was going to play this thing, he would either have someone teach me to play it properly, or he'd smash me over the head with it. So I took classical lessons for a year, which got me onto the right footing, using all the fingers and the right strokes of the plectrum. I think when you first go into an instrument, you need to be set in the right direction, otherwise you can pick up very bad habits. That first guitar was a Framus, a Spanish guitar made in Germany, and I kept adding pick-ups to it, and as I was into electrical wiring at that time, I ended up with loads of switches to the point where I wasn't sure quite what they were doing, but they looked good. I'd like to see that guitar now, but I sold it to buy a Hoffner three years later, which was 32 guineas, a lot of money in those days." Blackmore's early influences included Duane Eddy, "Big" Jim Sullivan, who was Britain's premier session guitar player during the 1960's, and who apparently gave Ritchie some instruction, Hank B. Marvin and Buddy Holly, while later on, at sixteen, his father insisted that Ritchie listen to Les Paul as well as to his current favourite, Chet Atkins. "Les Paul was much more refined, not the type of player you recognize when you first take up the guitar - there's always some sort of novelty you look for, and Hank B. Marvin had the tremolo arm and the very straightforward melodies which I could pick up, whereas Les Paul was very difficult to emulate. I left him till later, and even now I couldn't copy half of what he's put down." Ritchie joined his first group around the age of thirteen, although not playing guitar. "I was playing what was called the "dog box" - a tea chest with a piece of string and a broom handle, and you can play any note on it and sound vaguely in tune. I started that after hearing Lonnie Donegan, and after three years, I started to play rhythm guitar." This first group was known as the 2I's Junior Skiffle Group, although Ritchie was too young to ever visit this haven of British popular music, having to console himself with once standing outside. "Being at school, we had about twenty-five guitarists on stage playing in the band. None of us could really play, but it looked good, and we played in the school concert. We did three numbers, of which "Rebel Rouser", I think, was one, and when we started it, the audience started clapping, and because the amplifiers weren't very loud, they drowned the sound out, and all the twenty-five guitarists just went into oblivion. I suppose that group lasted just one day - we had a rehearsal that afternoon in the school, and I plugged my guitar straight into the mains, which wasn't too bright, and it blew up the entire lights of the school for fifteen minutes." Blackmore's first serious group came when he was fourteen-years-old, and was named, oddly enough, after an amplifier. "Watkins, the people who make amplifiers and tape recorders, had an amplifier called the Dominator, and I thought that the Dominators was a good name for a group. That amp cost me 22 guineas, and I remember it looked fantastic, a kind of triangle effect with speakers going in different directions. The first one I bought blew up, and the next week, I travelled by underground from Hounslow West to Piccadilly Circus, where they were located, to take it back, and they gave me a replacement, which I took all the way back home on the train. The curtains opened on our first performance, and that amplifier also blew up. I took it back to the shop, and this happened six times - I said that there must be something wrong with them, but they said there couldn't be, and they suggested that I tried the amplifier out there in the shop. I agreed and blew it up in the shop, which they couldn't believe, so they gave me a different amplifier, which they wouldn't let me try out, and they told me to go away and said they never wanted to see me again. Fortunately, that amplifier they gave me, which was a Fenton-Weill, lasted for a long time, but the Dominators, the group, folded after about six months - they were just school-friends." Ritchie's scholastic career was hardly a major success story, and he in fact left school when he was fifteen. "I couldn't wait to leave, but the headmaster tried to persuade me to stay, even though I was always in trouble, always getting caned for talking in class and being naughty. It was quite funny - in the mornings, I'd be awarded medals for throwing the javelin, and the headmaster would say that the school was proud of me, and in the afternoon, I'd be seeing him to be caned and being threatened with expulsion, which I found quite ironic, because he was such a hypocrite."  On leaving school, Blackmore worked as an apprentice radio mechanic at nearby London Airport, before joining a professional group, Mike Dee and the Jaywalkers, who gigged three or four nights per week. "We had gigs all over the place, a hundred miles away and more, and we had a Bedford van whose door wouldn't shut - those are the things you remember for a long time, and they're roots, part of growing up, I suppose. We played basically copy material, Shadows stuff, and all the steps that went with it, and the suits and ties.

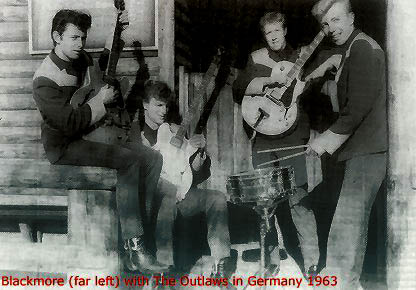

On leaving school, Blackmore worked as an apprentice radio mechanic at nearby London Airport, before joining a professional group, Mike Dee and the Jaywalkers, who gigged three or four nights per week. "We had gigs all over the place, a hundred miles away and more, and we had a Bedford van whose door wouldn't shut - those are the things you remember for a long time, and they're roots, part of growing up, I suppose. We played basically copy material, Shadows stuff, and all the steps that went with it, and the suits and ties.I was trying to be Hank Marvin, although I didn't have the horn-rimmed glasses or the physique he did, but I was playing lead. I was with them for about six months again, until they became known as the Condors, but I can't remember much about that time, because it was so long ago. Then Screaming Lord Sutch saw me, and wanted me to audition for his band - I went, and passed the audition, and I think Pete Townshend also went, but strangely enough, he failed. I was thrown in the deep end really with that band, because they were very professional, touring everywhere, very good musicians, and I had to learn quickly. I used to play through an echo chamber, and the first thing they said to me was that I had to get rid of it, and that I had to move around like Elvis Presley - we had these hip movements which we had to do in unison, which takes some doing for three-quarters of an hour at a time. But Sutch taught me a lot - I had a habit of disappearing off the side of the stage, because I was so shy, and all the people, especially my relatives and so on, would look for me, and all they could see was this guitar sticking out of the wings. But Dave Sutch took me out on stage and started throwing me about - I thought he was totally crazy, and I'm still not sure whether he is or not, coming out of coffins and dressing up in loincloths. In '62, '63, we were into a very heavy kind of basic hard rock, like Johnny Kidd and the Pirates, with a rhythm-and-blues base, and then the Beatles came out, and the Hollies, and it was all harmonising, and one had to sing. I didn't sing, in fact I could hardly talk at the time, and I was just into playing the guitar and very hard rock'n'roll and distorting guitar solos, which were out of vogue then - it was all pleasant vocal harmonies, and that lasted about four years until Hendrix and Cream came along. As for the Stones, I didn't think they were good enough musically. I thought the Beatles had it musically, but the Stones didn't impress me at all, and I still don't see it to this day. A good rhythm section, I suppose, but I don't think there was an outstanding musician in the band that I liked - I always look for one person in a band to like rather than just a conglomeration of guys moving backwards and forwards and not getting anywhere." Ritchie joined Screaming Lord Sutch in May 1962, and by the October of that year, had joined the Outlaws, whose lead singer, Mike Berry, had decided to leave the group. "The Savages (Sutch's group) actually kicked me out because I wasn't good enough. They'd had some really brilliant lead guitarists, and then the drummer and the bass player were going to join Cyril Davies and the All Stars, and I was just left to get on with something else. So Joe Meek (famed British record producer, often cited as the nearest UK equivalent to Phil Spector) heard about this, and asked me to join his band, the Outlaws, which sounded good to me, because the Outlaws were better known than the Savages. I was quite pleased, and about two weeks after I joined the Outlaws, Carlo Little, the Savages' drummer came back from Cyril Davies' lot, and asked if I'd like to rejoin, because they'd had second thoughts, and I said I couldn't, because by now I was obligated to the Outlaws. We recorded a lot as the Outlaws - there was a point in time when I'd put the radio on, and out of every ten records I heard, there must have been six where the Outlaws were doing the backing, and I'd always feel that I'd heard things somewhere before, and then suddenly realise that it was me on the record, but with somebody else singing who hadn't been present at the time we did the session, but had been dubbed on later. I think that session work with a session band like the Outlaws can be good discipline, as long as you don't take it too far. I did it for about a year, which is long enough, because you start to get a little clinical - even now, I find I'm a little bit clinical, and I get into a studio and think I'm doing a session and everything has to be perfect, and then the atmosphere goes, whereas someone like Hendrix just went in and was always like having a party going on, which is the right way to do it really." During this period as a member of the Outlaws, Blackmore played on numerous records as a backing musician for Joe Meek's productions, although he is unsure of precise titles and artists. "I must have performed on a good 400 records, with artists like Michael Cox, Danny Rivers, Freddie Starr, Heinz, even Tom Jones. Joe Meek's studio was a very small room, ten feet by eight, I think, with another room joined to it with all the electrical equipment in it, and that was six feet by six. Joe was very secretive about the things he did, and he'd often tell me that he'd been speaking to Buddy Holly who told him that he must do this record, which was Tribute To Buddy Holly, and all the Mike Berry things. He actually thought he could communicate with Buddy Holly, and other people like that." The period to which Ritchie is referring was from 1962 to 1964, and Buddy Holly, of course, died on 3 February 1959. Meek was certainly fixated about Holly, and it may be no coincidence that on the eighth anniversary of Holly's death, Meek blew his own brains out with a shotgun. "Being with Sutch and then working with Joe, I feel probably accounts for the way I am today, completely schizo - being thrown in at the deep end with these people, after having led a really sheltered life up to that point."  While the Outlaws were highly rated musically among their peers, and even backed such notable American rockers as Jerry Lee Lewis and Gene Vincent on several tours, their reputation was less than spotless on a personal basis - Blackmore himself was at one point, apparently, "deadly with a flour bomb".

While the Outlaws were highly rated musically among their peers, and even backed such notable American rockers as Jerry Lee Lewis and Gene Vincent on several tours, their reputation was less than spotless on a personal basis - Blackmore himself was at one point, apparently, "deadly with a flour bomb"."That's right - we had this habit when we were travelling in the van of buying four-pound bags of flour which we split open, along with eggs and tomatoes, and we'd throw these things at people we saw on the way, preferably old women in wheelchairs. But it got out of hand, and we became very cocky and started throwing them at policemen and all sorts of people. It was great fun, but it got us into a lot of trouble, until nearly every week when we'd be doing a session at Joe's, Joe would say that there was a policeman downstairs, and it would nearly always be me he was looking for, to the point where Chas Hodges had to cover for me. On one occasion, I could have been put away for three months, because some-body had complained that they'd been seriously injured by a flour bag, so Chas said that he'd thrown it and pleaded guilty in court. Luckily, it was his first offence, but it would have been my twentieth. It was a very strange period when I wrecked a lot of things, although I still don't know why - I used to have grave doubts about myself between the ages of seventeen and twenty-one, because I just wanted to smash things up and cause as much trouble as possible. To me, it was very funny, and I couldn't see why people couldn't see the funny side of it, but we were banned from nearly everywhere because we ruined so many things, and that was why we had to disband, because we couldn't get any work as a band - when we were throwing these flour bags and doing all this nonsense, we had our telephone number in big letters above the van, saying, "Please call the Outlaws", with a North London telephone number, so of course the police did, and that's why we were caught so often." Having been an Outlaw in more than one sense of the word, Ritchie next became a Wild Boy, the name of the group backing Heinz Burt being the Wild Boys. Heinz was initially part of the Tornadoes, another Meek-produced act and possibly the most celebrated part of Meek's stable due to their enormous worldwide hit, "Telstar", after which Heinz left the group for a solo career, although by the time Ritchie joined him, Heinz's greatest successes were behind him. "As the Outlaws, we provided the backing for his biggest hits - "Just Like Eddie", "Country Boy" and "You Were There" were the first and biggest, I think - but the Outlaws didn't go on the road with him, and when I left the Outlaws, he asked me to form the Wild Boys with him, which lasted for about a year, although it was a terrible band. We did a three months summer season at Rhyl with Arthur Askey, or Mr. Big Head, as he calls himself, and we got into a lot of trouble again. There was a 12-piece pit orchestra, and when they went home at night, I'd add notes to the trumpeter's part, and things like that, and the next day there would be this couple of bars of awful trumpet solo, which didn't go down too well." Despite this somewhat rowdy life, Blackmore was still determined to improve his guitar-playing ability. "I used to practise for about five hours a day, because I loved playing and felt that I had to improve, even though the band I was in wasn't very musical. They could hardly play their instruments at all, I felt, so I was in this weird position of playing three chord music and trying to extemporise in a way which I thought was quite good at the time. I thought the audience might have picked up on that, and wondered why I was in this band who were speeding up and slowing down and playing the wrong chords, and then there'd be a very good solo." At the start of 1965, Blackmore joined another semi-legendary seminal British beat group, Neil Christian's Crusaders, a band which, like Lord Sutch's Savages, at various times included many of today's notable musicians, including Jimmy Page. "At the time I joined, Neil Christian had his only big hit, "That's Nice", in the hit parade, and the band were going out on that success. I went along with people saying to me that they liked the guitar introduction that I played on the record, although it wasn't me, it was actually Joe Moretti." The period from the start of 1965 until the latter part of 1967 is particularly confusing - Blackmore spent part of this time in Germany, admitting to marrying and divorcing two German girls, several spells with Neil Christian, occasional returns to Lord Sutch (one of whose bands included four saxophonists as well as Blackmore), and a solo single of "Getaway" / "Little Brown Jug". "That was produced by Derek Lawrence, and in the band, I think, were Nicky Hopkins on piano, Carlo Little on drums, and Cliff Barton, who was a fantastic bass player. I'd always been kind of on the shy side, and I thought it was going a bit too far to call that the Ritchie Blackmore Orchestra, but that was the way Derek wanted it. I don't really rate that single - I played through a three-inch speaker, which I'd kicked in to give a fuzz box effect. Jimmy Page had the only fuzz box around, but with this three inch speaker being overloaded by 30 watts, it gave a similar kind of fuzzy effect." Shortly afterwards, Blackmore returned to Germany with bass player Avid Anderson and drummer Jimmy "Tornado" Evans, who were known as the Three Musketeers. "I was a little bit disillusioned with England, and I wanted to be somewhere else, anywhere, and I loved Germany. So I found this backer who was prepared to put up some money, and we became the Three Musketeers, dressing up as musketeers, coming on stage sword fencing as the drummer played two bass drums, which was unheard of in those days, and only being a three piece, which was also unusual. I have fond memories of that period, because the band was excellent, but it was far too advanced for the German public, because we used to play very fast instrumentals. They couldn't dance to it, and they couldn't understand what we were doing, coming on stage fencing and then going into an incredibly fast Django Reinhardt number or something like that - I don't think they were too pleased on the whole... I wish I had some recordings of that time, because I'd like to hear how I was playing in that period. After that, I came back to England, and back to Neil Christian - there were only certain groups before 1967 that would have pure guitarists like myself, who refused to sing or get involved in harmonies, but just played lead, so it was actually quite difficult getting gigs, because everybody wanted someone who could also sing. One of Sutch's bands that I joined was called the Roman Empire, and we used to dress up as Roman soldiers. For a publicity stunt, we marched through Oxford Street dressed like that, and held up a bus, much to the dismay of a policeman who arrested us, or tried to." Following this mayhem, Blackmore formed a short-lived band called Mandrake Root, which in itself was of little note, save for the fact that it led almost directly to the formation of the band, which initially made Blackmore a superstar, Deep Purple. The early origins of Deep Purple are complicated, to say the least. The group seems initially to have been the brainchild of ex-Searchers drummer Chris Curtis, who convinced a financial backer, Tony Edwards, that a group could be formed around him.  Among the other musicians he contacted to recruit members for the group was Blackmore. "Chris Curtis, who I'd met back in 1963 at the Star Club in Hamburg, sent me about a hundred telegrams to invite me to join his new group, which was first going to be called the Light, which lasted about one day, and then Roundabout.

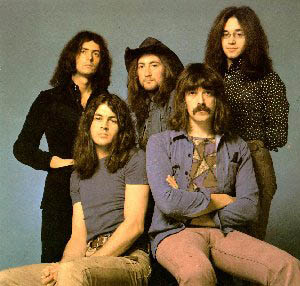

Among the other musicians he contacted to recruit members for the group was Blackmore. "Chris Curtis, who I'd met back in 1963 at the Star Club in Hamburg, sent me about a hundred telegrams to invite me to join his new group, which was first going to be called the Light, which lasted about one day, and then Roundabout.It's a strange story - I asked him who else was going to be in the band, and presumed that he'd be playing drums, and he said he was, and that he would also be playing lead guitar. So I asked what I'd be playing, and he said I would be number two, second guitarist, and I must always remember that he was number one and I was number two. I said OK, and asked who'd be playing bass, to get off the subject, and who'd be singing, and he said he'd be doing all the singing, and we wouldn't need a bass player, so in actual fact, it was just the two of us, and he was playing every instrument, including lead guitar, but I had to remember that he was number one guitarist. And I hope he takes this in the spirit it's meant, because it was funny, although I couldn't quite understand it at the time. He was always saying to me, "I'm number one, what are you?" and I'd go, "I'm number two". It was a very strange set up, but he did get one other player, Jon Lord, who was an excellent organist, and whose playing really interested me. We talked about it, and Jon was very interested in my playing, although he wasn't very sure about Chris either. Prior to getting together with Chris, I'd been stuck in Germany, living off immoral earnings. This woman was helping me out, and I stayed there for about a year, practising about six or seven hours a day, which was all I could do - there was nothing to do but practise and drink. At the end of that year, I saw Ian Paice at the Star Club drumming with the Maze, and I offered him a job with my band. He asked what the name of the band was, and who else was in it, and I told him that there was nobody else in the band, so he asked me how he could join. I told him he was the first member, and that we'd get some really good players, so he told me to let him know when I had the other members together, which I did, about a year later. I think it was the backer's wife who was really more interested in Chris Curtis than Tony Edwards was, and in about two weeks, we all saw where it was going, and I got Ian Paice involved, and then we had the semblance of a band, with Dave Curtis on bass first, and then Nicky Simper, and it sounded very good, with Jon on organ, Ian on drums and me on guitar. It was a really happening thing, and Tony Edwards saw this, and Chris Curtis seemed to fade out. I think he went back to Liverpool, and I haven't seen him since, but he was the first one to get Deep Purple together." With Lord, Paice, Simper and Blackmore himself, the only ingredient missing was a singer, a position finally filled by Rod Evans, who had also been in the Maze with Ian Paice. Deep Purple were an astonishingly popular group, almost from their first formation in March 1968 until their final dissolution almost exactly eight years later (after myriad personnel changes). However, their early records gave little clue to the fact that, within a few months of their debut, they would become one of the heaviest hard rock bands of all, one example from their first LP, Shades Of Deep Purple, being the choice of a Neil Diamond song, "Kentucky Woman", to cover. Hardly the obvious type of material, Ritchie? "I was quite happy playing it, because I just had no direction at the time and was very happy to be in a band with some financial backing behind us. We were living in a haunted chateau in St. Albans, and I think "Kentucky Woman" was Jon Lord's suggestion, putting it to the type of beat which Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels would have used. And it worked - I think it got quite high in the charts in America, as our second single." In fact, it was hardly a triumph, reaching number thirty-eight, a respectable, but hardly overwhelming position, especially as it followed "Hush", the group's debut 45, which peaked at number four in the USA, bringing almost instant stardom to the group. "Hush" was more my idea - I really liked the song, which I'd heard sung by Joe South, who had a small hit with it, and I couldn't understand why we had the hit with our version. It helped us a hell of a lot in America, but in England, we weren't known at all - we were playing a festival at Sunbury or Plumpton, and we were due on at seven o'clock and Joe Cocker was on after us, and the papers said that the show started with Joe Cocker, and that was the kind of press we were getting." After three LPs, all of which were substantially more successful in America than in Britain, Deep Purple experienced some personnel changes, which saw the departure of Rod Evans and Nick Simper, who were replaced by Ian Gillan and Roger Glover, respectively. "I could tell that the fashion was going to be for screamers with depth and an overall blues feel, which is why we got Ian - he had a scream, but also had a way of singing which was, and still is today, very different. He's got a lot of identity there, and you always know when it's Ian singing." This line up of the band, widely known as Deep Purple Mark II, is regarded by an overwhelming majority of Purple fans as the ultimate permutation of the band, with which Ritchie wholeheartedly agrees. "There was a chemistry, and basically, we were all very enthusiastic, plus the band was very musically inclined, I thought. Roger is an excellent catalyst who's very good at putting things together, Ian was a very good showman and a good looking guy who had an incredible voice, Jon was a very good arranger and a very good musician in the old school form, who could put it down on paper, and I was the mad irritable guitarist, I suppose, who certain people could relate to, and I thought I also played quite well. I worked on that image, because Jon had this gentleman image, Mr. Nice Guy, and I wanted to be the opposite, which is in my nature. I think you have to be yourself, otherwise the public sees through it, but I was embellishing it, blowing it out a lot, and I suppose that's why today a lot of people still think of me as the moody guitarist. Which I am, and I'm proud of it." Strangely enough, the first album released by the new line up was hardly the type of thing, which a "moody guitarist" would enjoy, a slightly bombastic item composed by Jon Lord and entitled Concerto For Group And Orchestra. "I didn't like that at all - I thought it was a total gimmick, and I told Jon that I'd be prepared to try it, but that I had a lot of heavy rock numbers that I wanted to put together on an LP, and that we'd see which one took off. I didn't want to be involved with the Concerto because of the novelty effect and the press we were getting out of it because of playing it at the Royal Albert Hall and all this business, but I said that if the next LP, about which I had some very firm ideas, and which was Deep Purple In Rock, didn't take off, that I was prepared to play with orchestras for the rest of my life. So we agreed to see which way the public wanted us to go, and the Concerto was a success to most people, but when we did In Rock, they went really crazy, thankfully, because that was the music I was into." With the release of Deep Purple In Rock, the tide had totally changed for the group in Britain. It became the group's first UK chart album, closely following the success a few weeks before of the single which would prove to be the group's biggest hit 45, "Black Night", which reached number two. "Black Night" was a total rip-off - I stole the riff from Ricky Nelson's record of "Summertime" (the George Gershwin song). The lead guitar playing on "Summertime", which was by James Burton, is the intro to "Hey Joe", and then a bass figure comes in which became "Black Night". As soon as I heard "Hey Joe", I thought if Jimi Hendrix can take that lead guitar line, I'll take the bass line, and consequently we both had hits with them, which is quite nice really, although poor old Ricky Nelson didn't get anything. "Speed King" also had Hendrix connections, because it was based around "Stone Free". Roger wrote most of that actual riff, I think, and that was the first hard heavy metal rock'n'roll track that we'd written, and we were very pleased with it, although there are some parts which sound similar to "Stone Free". We wanted to incorporate that type of thing, and Ian (Gillan) wrote some innocent lyrics really, which the Americans interpreted as being about drugs, whereas in fact the song's just about a fast driver." A most interesting facet of the group's song-writing ability was that a backing track would be completely recorded, after which it became Ian Gillan's job to construct lyrics and subject matter, often without a title. "Led Zeppelin used to do the same thing to Robert Plant, he told me, but that was the way it was - we would always write the backing track and not even think about what was going to be sung over it. The fact that it was a good backing track was good enough for the band, and if Ian couldn't sing anything over it, it was just too bad and meant that he was inferior, so he had to sing around these certain riffs, which must have been very difficult sometimes. Hearing these things in retrospect, people would say that it was very clever how the voice suddenly stopped and the guitar took over with a riff, but really it was just that it was an awkward riff to sing over, and that's how those things came about. I know it dispels the myth of working together, but we would go in for one purely instrumental day, and Ian would be in the studio for the next day to put the vocal down." Although they were tremendously successful during the nearly four years they were together, Deep Purple Mark II worked under a good deal of pressure. "We were working all the time, either on stage or in the studio, and we had about a week off each year, at the most, in between dates. I went down with hepatitis, and so did Ian, and I even had a bit of a nervous breakdown in '69 because I didn't want to go to America - I loathed America, and I didn't want to have anything to do with it. I wanted to stay in Europe and just go around quite merrily doing Germany, France and England, but the managers were always saying that we must break America, which is true, I suppose."  Nearly ten years later, how does Ritchie view the work of Deep Purple Mark II? "I can't really say that I've heard any of it recently, because I'm very bad at collecting and listening to what I've done, and I don't get off on what I've played, except for a few tracks that I consider to be very good and very emotional, but I didn't consider a lot of the Deep Purple material that I was on to be very good, now or even then. I could see that the public bought the records, and that it was commercial, but I really didn't like half the stuff we did. But there again, I think that was me being me, just being bloody moody and saying I was tired of a song within an hour of playing the riff, and by the time that I heard the end result, I hated the whole thing. It may sound strange, but I just didn't like most of what we put down, which is probably what keeps turning me on now, keeps pushing me on to believe that one day, I'll be able to play something that I actually like."

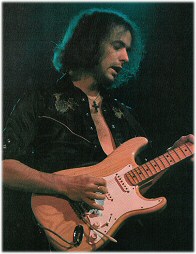

Nearly ten years later, how does Ritchie view the work of Deep Purple Mark II? "I can't really say that I've heard any of it recently, because I'm very bad at collecting and listening to what I've done, and I don't get off on what I've played, except for a few tracks that I consider to be very good and very emotional, but I didn't consider a lot of the Deep Purple material that I was on to be very good, now or even then. I could see that the public bought the records, and that it was commercial, but I really didn't like half the stuff we did. But there again, I think that was me being me, just being bloody moody and saying I was tired of a song within an hour of playing the riff, and by the time that I heard the end result, I hated the whole thing. It may sound strange, but I just didn't like most of what we put down, which is probably what keeps turning me on now, keeps pushing me on to believe that one day, I'll be able to play something that I actually like."One song, which Ritchie will admit to liking from his Deep Purple years, is "Smoke On The Water" from the 1972 LP, Machine Head. "Yes, there's a story behind that, which was that we went to see Frank Zappa playing in Montreux, where we were recording, and somebody shot a flare gun off which set the roof on fire, and the whole place went up and was gutted within two hours. Everybody was running out of the place, but I didn't know why - I thought it was an intermission or something, because I had got tired of Frank Zappa within the first ten minutes, and I was more interested in this girl who was quite well endowed. I took her outside and was talking to her, and all these people were running past me with white faces, and I presumed it must be an intermission and that they were going to get ice creams until I saw the smoke coming out and realised something was wrong. It's a good job I realised it, because otherwise I'd have been with this certain young lady somewhere, in some kind of cupboard, up to some sort of mischief, and I would have been burnt down with the place, because it was a habit of mine to disappear into cellars and places... We had already recorded the backing track before the fire, and we did it in about four takes because we had to - the police were banging on the door, and we knew it was the police, but we had such a good sound in this hall that we were waking up the neighbours about five miles away because the sound was echoing through the mountains. We had just finished it when the police burst in and said we had to stop, and since we'd finished it, we did. Then Ian wrote the words after the fire - he probably didn't have anything else to write about. (laughs)" Not long after this, the newest members of the band, Ian Gillan and Roger Glover, decided to leave the band, Gillan to form his own group, and Glover, initially, to become a producer. How had Blackmore and the remaining members of the band felt about the split? "I guess there's two answers to that, the professional one and the honest one, and the professional one is that we were stunned, as they say. But really, it had been coming for quite a time - I wasn't getting on with Ian too well, and it had been three years or more, which was long enough for me to get on with anybody, so I more or less said that I wanted to leave in 1973, at the same time as Ian Gillan, and form my own band, which was going to be with Ian Paice and Phil Lynott. It was suggested that it would be better if I stayed because of all the financial things involved, and I said I would stay, but that if Ian was going, I thought we should probably replace Roger, and the band decided that they would rather have me in the band and get another bass player. So I was the cause of Roger being asked to leave, which I wasn't particularly pleased about, because he's such a hard worker and a nice guy and a very good musician, but I thought his ideas were a little too commercial. I was dying to get into some blues, some very heavy stuff, like Bad Company were playing, but Roger was into a lot of vocal backings and the fairy dust effect which thankfully sells records. He always puts a glossy sheen on things, and I liked the more earthy side of music, he was more into pop, and I was more into non-selling rock. I suppose that I considered myself a heavy metal guitarist, although people often say I'm not because I have finesse and I play with subtleties and ups and downs, but I don't care what people call me as long as nobody calls me a folk guitarist." The replacements for the two outgoing members of the group were singer David Coverdale and bass player Glenn Hughes, but it seemed to take very little time before Blackmore discovered that he had probably been better off with the members who had left. "I underestimated Ian's talent and the way he sang, so I was definitely wrong there. I didn't like the way he sang after a couple of years of listening to it, but on reflection, it was much better than when we got the other two in - which is not putting them down, but just saying that I didn't like what they did. I didn't stay much longer, because it started to become a soul type band with the Stormbringer album. It became very, very funky and it wasn't a rock'n'roll band anymore - to me, it's either classical music or rock'n'roll, it's black or white, and I don't like funk music or soul music, which I think Ian Paice and Jon are still into to this day." On this occasion, there was no attempt to convince Ritchie to stay in Deep Purple. "I left because I'd met up with Ronnie Dio, and he was so easy to work with. He was originally just going to do one track of a solo LP, but we ended up doing the whole LP in three weeks, which I was very excited about. It wasn't that I found Ronnie Dio and that I was into this band Rainbow, it was that I was determined to leave Purple, because I no longer respected their music." So in May 1975, Ritchie Blackmore finally left Deep Purple, although there has been constant pressure ever since for the group, and preferably the Mark II version, to reform, if only for a brief tour and album. Will it ever happen? "The longer it goes on, the more I doubt it." This major change in Ritchie's career seemed a good point to discuss matters such as practice, choice of guitars, technique and so on. "I practice more mentally, which is an easy way out of that one, and means in other words, that I'm lazy and don't practice at all, which is what everyone means when they say they practice mentally. I practice for an hour or two every day, especially when I have time off. When it comes to new guitars, I'm very unadventurous, I play a Fender with my own special concave wood effect on the neck, and I'm very satisfied with it, and the same goes for amplifiers. People offer to let me try things, but I don't, which is probably detrimental to me - I hear certain sounds, like phasing and things like that, which I should really try, but I never do - for some reason, I'm too busy either practicing or just thinking. I don't experiment enough with my life in general, and that goes for music, food and a lot of other things, although I'm starting to experiment with hotels, and I now stay in as many places of historical interest as I can find, much to the regret of our road manager, who has to check me into castles and weird haunted places all over Scotland. During my time with Deep Purple, I'm sure my guitar technique improved, because I'd never played to so many people, and for once in all the years, I could see an actual point in all the practicing. I mean I practice just because I love to practise, but then I saw that there was this other avenue where there were actually people willing to listen. Then I thought it was maybe because I'd practiced so much. I'm certainly no better than most guitarists, it's just that I've practiced a lot more, so if I have a faster right hand, it's just that I'm always shaking it around in practice. I think technically, but I think I lack a lot of mental innovation, and in that way, I'm not as creative as I'd like to be. I'm not pitch perfect and I don't have a very good musical memory, so most of what comes out in my practicing is enthusiasm. I never particularly wanted to be distinctive as a guitarist - I'd rather be distinctive as a person - and the guitar was the thing I could do better than anything else." Reverting to Rainbow, the band Ritchie formed after leaving Deep Purple, one of the most outstanding features of the band, aside from its music, has been an almost constant spate of personnel changes - during the seven years of the band's existence, no less than seventeen musicians, aside from Blackmore himself, had played in the band, which never exceeded a five man line-up at any time. "I think the problem is that they don't like me. (laughs) Really, when I was with Purple, I was so confined with those five players, and we had our limitations within the band, which weren't that many, but they were there, and I was conscious of them, so that when I got a new band together, I didn't want any limitations whatsoever, which, the more I get into it, is actually impossible. Every band has to have limitations, but I find that very hard to accept, which is why I keep changing members." It would be pointless to list all the comings and goings which occurred within Rainbow, and for the purposes of the radio version of this series, we chose a number of tracks from the various Rainbow LPs, and asked Ritchie to talk about them. From the 1977 live LP On Stage came the simply titled "Blues"... "Playing the blues is a challenge on guitar, because you're so limited within the minor mode of the blues, and if you start to go off into majors and diminished scales, it doesn't sound right, so you limit it to about six notes, and certain people can pull it off, although I don't know who they are at the moment - there must be somebody! But it's very difficult within the blues frame to come up with something that's different, and that's what I find a challenge with the blues - it's a case of slowing down and playing three or four notes very well with a very good vibrato, which is a lot more difficult than it would seem on the surface. To contradict myself, blues can be very easy if you're totally relaxed and you've been drinking, and then it's very hard to produce edge music, music with any sort of intensity, nervous adrenalin type music, and I find that side of things fascinating - it's hard to live with it, because you're continually nervous, but I wouldn't change it for the world, because I like being on the edge of the Rainbow." Next, "Kill The King", which can be found on the 1978 LP, Long Live Rock'n'Roll. "I have no idea what the lyrics to that song are about, because with Ronnie (Dio), I didn't know too much about the lyrics, and they were very abstract, most of them talking about demons and devils. The riff was just a very fast one which is my typical type of block chord in G sort of riff - I must stop writing in the key of G - and it's just a very frantic, upfront, no nonsense number, which you either love or hate, and I knew that when we were playing it. We recorded that particular number in a chateau in France that had been haunted by Chopin, and it seemed very weird that we were doing this out-and-out rocker when we should have been full of melodic content and playing in a very sympathetic way in sympathy with the environment of the chateau, whereas we were crashing out "Kill The King" and disturbing all the local residents, but it's still a very interesting song." Rainbow's greatest successes in the British singles chart came after Ronnie Dio had been replaced as vocalist by Graham Bonnet, the first hit for this combination being "Since You've Been Gone", which reached number five during the autumn of 1979. Unlike the vast majority of the tracks recorded by Rainbow, this song was a cover version, which had been recorded several times before, and had been written by Russ Ballard. "I first heard that at my manager's house, and he asked me what I thought of the song. I said it was a hit, and wanted to do it, and he was quite surprised. We did it in about two takes, because Cozy (Powell, Rainbow's drummer for five years) hated it. It was released and it was a hit, which we knew all along it would be, and it was kind of a way of getting our foot in the door and getting a broader public, but at the same time we weren't letting the side down. "I Surrender" (a number three hit in Britain at the start of 1981) is a similar type of song, and I'll always stand by those songs, because they're great songs - people say, "How can you do that? How can you sell out? You're a heavy metal guitarist and known to be un-commercial", but that's rubbish, and I'll play anything. If it has a good melody, that's all that matters, even if it's "Over The Rainbow" by Judy Garland (which has been used to close the Rainbow live show). I did "Since You've Been Gone" because I thought it was an extremely good melody, and I can listen to it now and feel quite proud of it - I'm more proud of that song than I am of some of the Deep Purple songs, which were kind of underground hits, like "Woman From Tokyo". I can't stand things like that." For many listeners, "Since You've Been Gone" was "made" by a typically attacking Blackmore's solo, which came at the end of the track, almost like an afterthought. Was it a conscious decision on Blackmore's part to tack on a guitar solo at the end of what had been a heavily vocal-dominated track? "I wasn't conscious that I had to put it in. I didn't want to put a solo on the end, but everybody insisted that I should kind of put my mark on it, but I felt that I didn't want to ruin the song, because it was perfectly good enough as it was, and stood up as a great song, so why should I have to start improvising at the end of it? But at the same time, because I have a lot of self-confidence in certain respects, I felt that it didn't matter whether or not I put on a guitar solo, so I just played over the ending, and they kept it in." Graham Bonnet's sojourn as Rainbow's vocalist was brief, and for the 1981 LP, Difficult To Cure, he was replaced by Joe Lynn Turner. Turner, however, was not featured on the LP's title track, which was actually largely derived from Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. "I remember watching a football match during the 1970's between Germany and Holland, where they had 90,000 people singing this tune, which sent shivers up my spine. Ever since that day, I've really loved that particular melody, although I don't especially like Beethoven. I know it's very easy to cop a tune like that, but again, it had the melodic content, and I used to throw it in as a kind of added bonus on stage." Although Ritchie's name has appeared quite frequently on song-writing credits, he refuses to consider himself as a songwriter. "I'm a riff merchant - export and import riffs and chord progressions and vague melodies, but when it comes to lyrics, I don't have much to do with it. I'll often think of a theme, like "All Night Long", which was about seeing a girl off the side of the stage when you're playing live, and she looks quite nice, so you want to get to know her, and that song was loosely based around that. I had some lyrics for that which I gave to Roger Glover (yes, the same Roger Glover whom Ritchie had caused to leave Deep Purple, but who became Rainbow's bass player / record producer in 1979, since which time the group have experienced their greatest success commercially), and which he changed around a lot, but I don't usually come up with lyrics at all - I concentrate on construction and I always have a vague melody in my mind." So had he ever thought about taking a leaf out of Jeff Beck's book, and making completely instrumental albums? "I've thought about it, but not in the Jeff Beck jazz / rock style, and even though several of my influences were guitar-based trios, like Jimi Hendrix, I wouldn't front a trio, because it's too much of a strain. Not on myself, because I've been in several three-piece groups, but on the audience, because I think it's too much for them to take for an hour and ten minutes, with just the lead guitarist taking the breaks. That gets too monotonous for me - I could handle it, but it doesn't appeal to me, and even with Hendrix, I always thought that there were only so many solos he could take before you wanted another instrument to come in, even if it was a trombone, just to change the atmosphere a bit." It's difficult to sum up Ritchie Blackmore tidily - it would be easy to suggest that his guitar does his talking for him, but perhaps his answer to a question about the future should remain his epitaph, at least in this volume. "I shall remain as stubborn as I've always been and given enough time and patience, I might come out with something worthwhile somewhere along the line. I have the ambition of a slug, and I'm not interested in goals of any sort, and that's why I don't hang out in the right places and talk to the right people and do the right things, probably. The only way I can do certain things that appear to be right is because I feel that it's inside me - I love playing the guitar, but I don't like being involved in everything else that goes with the business. I don't really understand myself, and my parents certainly don't understand me, but in a way, I like to leave it like that, because I'm never bored with myself. I'm often very confused with myself, but never bored." © Stuart Grundy & John Tobler, BBC Books 6 March 1983 - [Thanks to: Kostik] |