|

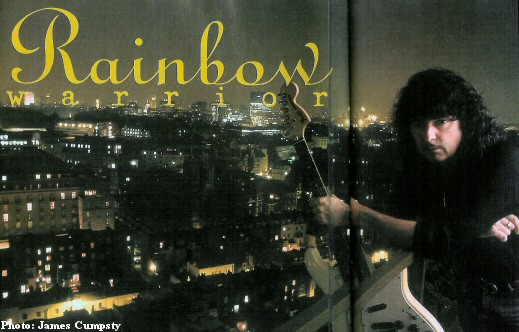

Rainbow Warrior It's not often in this job that you're almost knocked off the 17th floor balcony of a top London hotel by a squad of police marksmen, thinks Neville Marten. Trust it to happen on a Ritchie Blackmore interview...  If a talk with the Man In Black isn't a daunting enough prospect - we've all heard the rumours of how he

eats interviewers and spits out the gristle for The Stranglers to squabble over - having actually broken the ice, and made friends, Ritchie nearly got us all shot! It was only three days after the assassination of the Israeli Prime Minister and our hotel was in the heart of London's Embassyland.

If a talk with the Man In Black isn't a daunting enough prospect - we've all heard the rumours of how he

eats interviewers and spits out the gristle for The Stranglers to squabble over - having actually broken the ice, and made friends, Ritchie nearly got us all shot! It was only three days after the assassination of the Israeli Prime Minister and our hotel was in the heart of London's Embassyland.When James, Guitarist's intrepid, photographer, persuaded Mr B that a night shot over the city could be had from the balcony, surprisingly he was happy to oblige. Here's where we nearly created an international incident! In his pocket Ritchie carried a laser pen - "You can send a beam over a mile with this thing," he chortled. But the Special Branch, who were patrolling the roof of the Embassy opposite, had copped our little escapade; they could, see camera flashes and some strange man dangling something (a Fender Strat) over the precipice 200 feet up. Let's say they had become 'interested'. It was at this point in the proceedings when Ritchie decided that pointing the laser their way might provoke a bit of fun (laser; rifle night-sight; armed- police over the road; geddit?). And it was only by wrestling him to the floor and physically removing the thing from his clutches (actually we just pleaded with him on our knees) that prevented certain retalliation from half a dozen kalashnikovs! He likes a laff, does our Ritchie. But he wasn't laughing the previous Friday night when his beloved white Stratocaster nearly walked right out of Hammersmith Appollo: "Bloody right," exclaimed the man on whose shoulders sits the burden of having invented Yngyie. "I left it on the ground and I was doing a Hendrix thing,letting it feed back and thinking, This is Wonderful. We all went off stage and it was still feeding back. Then I got round the back, just waiting to do an encore, have a swig of beer and someone said, Have you got the guitar? and I said, No, it's on the stage. But my guitartech said, I don't think it is. So it was panic stations! And then suddenly this guy came up from the audience; somebody had got him and he just walked up to me and said, Here's your guitar. I thought in the crowd it would have got messed up, but it was even still in tune!" The Man In Black is back because he's formed a new band. It's called Rainbow and you might have heard of this little outfit before. Ritchie sighs: "When I left Purple, I wanted to form another band and I really didn't want to call it Rainbow. But the record label assured me that I had fans who'd buy the record if it was by band that was related to me. Hence Rainbow." Blackmore didn't want the big guns coming in and he didn't want a band made up of session people. "I wanted a family kind of band," insisted the moustachioed one, in a rather cultured British accent that belies both his West Country origins and his longtime residence in Long Island, USA, "because if we're going away for two or three months I like it to be five guys all having a good time. Contrary to my image, I like to muck in with the guys and spook people out with ghost tricks and things" - and laser beams; he later had some poor guy walking around the hotel lobby with a red pin prick of light fixed on the middle of his forehead! The new Rainbow personnel include Doogie White, on vocals, Paul Morris on keys, bassist Greg Smith and original Rainbow drummer John O'Reilly. "The keyboard player actually found me," he exclaims. "I was playing in this club in Long Island and I had an arrangement with this band that they couldn't advertise me but they could spread the word; people would come along and we all had a good time. Except that a few people did come up and say, You, shouldn't be playing these clubs, you know; you should be playing Nassau Coliseum! Anyway, Paul Morris approached me one night and said, Do you remember me from 10 years ago? I was the one who was going to take the job before David Rosenthal came along. So I re-auditioned him and he was very good. The bass player I got through our drummer at the time. We had another bassist, but he wasn't gelling; he was just off on his own; very good player but a little bit too 'leady'. And we got Chuck on drums who I've always favoured since the old Rainbow; he's a slight jazzer, but I like that jazz inflection because if I'm doing a little bit of syncopation he catches it every time. "The original singer, once we started playing dates I noticed that he couldn't improvise. He had a great voice, similar to Bryan Adams, but when we'd do a blues of something he couldn't improvise at all. At first I thought he was just having an off day, but after about a week of rehearsals he's saying to me, What do you think of the drummer? What do you think of the bass player? And I'm thinking, Actually I don't know about you! It turned out he was just a copy vocalist. Great guy, great voice, but I couldn't take him. So Ritchie had to look for another singer and here's where fate took an eerie hand. "I was in the house with my girlfriend and she said, Who's on this tape? and she put it on. And I'm going, Who is this? Sounds good. Took the tape off and it said, Doogie White, call London... So I called him up and said, Look, we really like your stuff, are you interested? And he said Yes. I asked him where the tape came from and he said, Oh, I just gave it to your road manager one night in London. And we have this box full of such tapes; why she pulled that one out, I don't know."  There goes a story about Ritchie auditioning a musician for a tour and saying: "There are two rules in this band: rule 1 is, NO EXCUSES; rule 2 is, NO EXCUSES." Whether this is true or not who cares, but one does get the impression that this man is, shall we say, a bit of a stickler. "Let's say I'm demanding," smiles Ritchie. "The thing is, a lot of musicians are lazy, including myself, and they could take the easy way out, which is, Hey, let's get drunk and throw down anything. But there's got to be a reason for playing and to me melody is very important and the song is the most important. People say, Let's just have a jam. Well yes, I love to jam, but then they say, Let's put that down as a song. But it's just a jam; there has to be, a structure there for me. I know sometimes I get too structured and tend to come off playing very sterile, but that's something I have to sort out for myself."

There goes a story about Ritchie auditioning a musician for a tour and saying: "There are two rules in this band: rule 1 is, NO EXCUSES; rule 2 is, NO EXCUSES." Whether this is true or not who cares, but one does get the impression that this man is, shall we say, a bit of a stickler. "Let's say I'm demanding," smiles Ritchie. "The thing is, a lot of musicians are lazy, including myself, and they could take the easy way out, which is, Hey, let's get drunk and throw down anything. But there's got to be a reason for playing and to me melody is very important and the song is the most important. People say, Let's just have a jam. Well yes, I love to jam, but then they say, Let's put that down as a song. But it's just a jam; there has to be, a structure there for me. I know sometimes I get too structured and tend to come off playing very sterile, but that's something I have to sort out for myself."So does one of the finest rock soloists of all time fret about his lead breaks? "If we were in a studio for, say, three months, at least two months and three weeks of that would be getting the song right. Then I'll spend a week on my bits and by that point I've forgotten what I'm doing anyway! I'd love to just go in and, one take and that's it; done with emotion and feel. After that it becomes sterile and after the third hour you start repeating yourself and I do love to be spontaneous, once I know the structure and foundation." So can Blackmore discipline himself in the studio or does he need direction? "A lot of the time I do need direction," admits the maestro. I find that I'll have so many ideas in my head and if there's a producer there I'll go, You know, I hear this rhythm part here, but doubled; maybe there should be a big riff here, but maybe that riff should change halfway through. And sometimes I go up my own arse because I end up not doing any of it. So I need someone to go, You had a good point there, let's finish that and then go back to the other idea you had. That's what I need; someone to sort out my confused ideas. But I sometimes sit down and wonder to myself, Why am I taking five hours on a backing track which anybody who's been playing three weeks could play? Then it comes to the solo and I'll have five minutes on it and someone'll say, Okay, it's late, shall we knock it on the head? That's when I think there's something wrong here with the priorities! And it's not the producer's fault, it's my fault!" Perhaps it's just the natural progress of big bands, big money and limitless studio time, but it wasn't always like this. It was worse! "There was a time," continues our laser-toting buddy, "between about 75 and 81, when I'd go on all night doing these solos. I'd go in with Martin Birch and we'd start at, say, eight o'clock and do two solos and I'd say, Let's do another one, and he'd say, What do you think of the sound? I'd go, A little bit more ambience; move the mikes around? Then we'd have a few drinks and now it's 10 o'clock. Okay, ready now. By the way Martin, did I ever tell you that ghost story...? And we'd get into telling stories. That would go on for a couple of hours and then it's midnight. Okay, let's get back to work. We're getting very drunk at this point and it's, I could do one better than that; that's awful; that one's not bad; we'll keep that. We're still drinking and telling stories and now it's, four or five in the morning and I've completely lost the plot, but I'm going on. Must do another one. But around the 'Machine Head' time I'd take about 10 minutes per solo and before that I'd do it in maybe two minutes. Which is interesting, because you can say just as much in two minutes as you can in two days. Sometimes more! "Even the last album, I went in and did one or two solos and went, That's it, otherwise I'm going to start repeating myself and I'm tired of hearing my solos being just too worked out - although they're not worked out." The most frustrating thing for Ritchie is that he can't seem to get onto tape what he can hear and what he knows he can play. "If I suddenly picked up the guitar right now, I might play something really well. Someone will go, That's it, get the mikes in, we'll tape it. But I've lost it. It's gone and the more frustrated I get, the more I start clamming up. I feel like those fishermen who come back and say, I really had this six foot shark, but I caught this one instead." It might seem to the more cynical minded that many modern guitarists - even some who would cite Mr Blackmore as their prime influence - get round the creativity problem using machinegun tactics. Did Ritchie ever fall into the speed for speed's sake trap? "In the beginning, between age 15 and 20, I would try and play as fast as I could. And then I started trying to physically slow down, because I was playing a blur of notes that were meaningless. And the hardest thing for me was to slow down, hold a note, do a vibrato, say something with the one note. I have to consciously think of the vibrato whereas most blues players use vibrato naturally, but I have to consciously do it; hold the note, vibrato, give it some colour." So if blues players develop a natural and fluid vibrato, we could probably surmise that Blackmore was not a follower of blues bands and that his classical, arpeggio-based style came from elsewhere. "Well, first of all I was taught classically, so I always used my little finger and was told not to play with my thumb over the top of the neck. But the actual classical style that people refer to in my playing came from a group called Nero And The Gladiators, who I used to go and watch when I was 15, at Southall Community Centre. They had Tony Harvey on guitar, as I remember. But they did In The Hall Of The Mountain King and other classical things and I thought, Ah, they're mixing the classical with the rock. I also liked Bee Bumble And The Stingers' Nut Rocker; that's a great tune. So all that stuff caught my ear. I love melody and I love chord progressions. I'm not too keen on the two or three blues chords and see what we can do over that. I do like to hear dramatic stuff. For instance, Grieg's 'Peer Gynt' suite, I heard that when I was nine and... Hall Of The Mountain King caught my ear. I thought it was so majestic and dramatic and almost frightening, because it was the witches in the caves with the long fingers. And when you're nine years old, you're thinking, What's going on here?" If the country held a 'rifferendum', Ritchie's name would be right near the top - Blackmore, Page and Iommi are surely the Riff-finder generals of British rock. You may be surprised to find that these dark Satanic fills often come from... watching adverts on telly?! "There's such great music to some of those adverts," insists the guitarist, now slightly less intimidating as I picture him doing the Daz whiteness test. "No, really, you can't help but think, That would sound really good if I change this around or that around. I do it all the time, because I don't listen to the radio any more; I don't have much idea of who's big - or small. I find it very difficult turning on the radio these days, even in the car. I'd rather have silence." For a man who's used a Strat and a Marshall for as long as most of us can remember, Blackmore has always played with the biggest, fattest, creamiest sound going. Shurely shame mishtake, Moneypenny? "In the old days," Ritchie digs back into the memory vaults, "I was very happy with my sound, which was a Gibson 335 and a Vox AC30. That got me the right edge and the right sustain, without being too distorted." But with Deep Purple, things had to change: "When the Purple thing happened we had to get big amplifiers, because Jimi Hendrix had big amplifiers and Cream had big amplifiers. But when I plugged into the Marshall the first time it sounded like shit. So I went to the Marshall factory and I knew the guys there; all very nice guys. So I said, I want the Vox sound but with a Marshall and they said, We can do that easily. But every time, I went back I'd tell them it wasn't quite what I wanted. So they said, Bring your Vox in. So I took it in and they tried to get the sound. They got close but I was still going, I want more of an edge; it's all woolly. Meanwhile, all the women would down tools on the assembly line, saying they weren't going to work with him making all that bloody noise. Then Jim Marshall would arrive from the office over the road saying, I knew you were here, I heard you right down the road. We had a great relationship." In the end Marshall came up with a solution: they would take Ritchie's heads (the 200 watters!) and build an extra output stage - and this was long before Van Halen and all the LA hot-rodders! "That was much better," confirms His Loudness. "It was funny because they said, If anybody asks for your sound, we're not going to tell them, because we're not going to do this again for anyone! So they built an extra output stage and it was a great sound, but it was coupled with a fuzz box, which I would have just on, and this tape recorder - I had this tape recorder and there was one in put side and one output, and if I overloaded the input and kept the output down, it would just give enough sustain to make it sound really sweet. But Marshall boosted my amp to 280 Watts, so I had the loudest amplifier in the world made by Marshall - by mistake, more or less." So Blackmore had Marshall modify his amp heads, but when it came to 'adjusting' his favourite Fender Stratocaster, he decided that DIY was the order of the day. "When I was 14 or 15, a friend of my brother had a very old classical guitar" explains Ritchie. "I was playing it and I thought, This feels really good; the wood was scalloped between the frets, but only because it was so old. It must have been 70 to a lOO years old and it was just worn away, and I thought, This feels so good, I should do it to my guitar. You see I always had trouble holding a note, because I like a low action and if I pushed a note across the fretboard it would tend to slip back under my finger. And after chiselling out a few bits and sandpapering my Strat, it felt much better. Then I went more and more until I got to the point where it was really scalloped. I play chords very lightly, just touching the strings, but anyone else who picked up my guitar would push them down until they reached the wood, so it would go sharp. And they'd say, I don't know how you play this thing! Yet I'd play it and it would be perfectly in tune." Of the crop of classic British guitarists - Clapton, Page, Beck, Green, Blackmore et al- there are those who would tout Ritchie as the best - he certainly had the most technique. So why do EC and the others seem to receive all the acclaim? "Every lead guitarist should be thankful to Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck," he states without hesitation. "They really started the whole thing off. I admit I wasn't a big Cream fan, but if I was next to Eric Clapton now, he's such a nice guy and he does have a technique and he's very much himself... I'd listen to Eric play before all these guys who just fly up and down the neck. And he did have that vibrato and he did turn me on to the Fender Strat. So it's easy to knock somebody, but when you think back he did an awful lot. Of course then Hendrix came along and did the guitar thing, too. But Jeff was the best guitar player. He was pushing with Shapes Of Things and that was amazing. For someone to play like that, who the hell was this guy playing Indian seales? I loved all that stuff. I've always been a big fan of Jeff's." Okay, Jeff has his Fender signature model, Eric has his, even Malmsteen has one. So why no Blackmore Strat? "Actually Yngwie was at the concert the other day. He's a very good guitar player and I think when he gets older he's going to calm down a bit; when he stops showing off he's got a lot to say. But he's still going through that, 'I'm the fastest' thing. He's got a lot of great ideas but I think he needs to see a therapist and calm down. As regards Fender, they would often call me up - well, not that often - and say, Do you want your own model? and I'd say, No, not really. Does it mean me talking to you on the phone for hours? Well, just five minutes, actually. And to my own detriment I'd think, I don't know if I need this, I'd rather just go for a walk. But I'm sure most players would say, My own model? Great! But I firmly believed the guitar I had was good enough. "Then it so happened I wasn't touring for a couple of years, so I actually had some time to collect my thoughts and call a few people back. I told Fender that whenever I get their guitars I glued the necks in. The first thing I do is loosen all the strings and pull the neck across, because the top E is nearly always falling off the edge and the bottom E is on by about a good quarter of an inch. I don't know what they've got against the top string! So I started gluing the whole neck so it would stay in position. And then I noticed that you got a better sound, a better resonance if the neck and body are like one piece of wood. So they did that and of course they scalloped the neck. I like a thinnish kind of neck; I know Jeff Beck has an unbelievably fat neck, something ridiculous. But I like a thin neck and very big frets. And I said, I never use that third pickup, I might as well just throw it away. So I have the two way switch that goes treble/bass, because I don't want to hear that little thin sound that you get with the other pickups. So it's just a two pickup job and they're Fender's standard new pickups - they were raving about them being very hot." Finally, when Deep Purple's original line-up got back together recently it looked like we might be in for some more of the best of British rock. But sadly the fragile egos of those involved meant it all fell apart. Is it really that difficult to work with people who are so set in their ways? "It is for me," states the guitarist unequivocally. "I'm set in my ways and they're very set in their ways. But I'm 50 now and I want to do rock'n'roll for maybe another couple of years - I say that every couple of years! - and I wanted to have a last bash at being with some guys that I want to be around; some fresh guys that don't have egos. Okay, so with the new Rainbow I'm taking a chance. I could so easily have just sat back in the old armchair, but I felt it was for an honest reason that I left Purple. I wanted to play better music. Some people might think, Oh, I don't know about that... But why else would I leave? What's the point of me leaving? I could easily just have just sat there and said; Yes, I'm the guitarist in Deep Purple; I'm very comfortable thank you very much..." © Guitarist (UK) January 1996 |