|

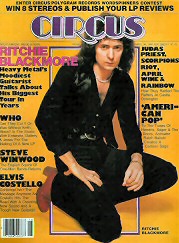

Ritchie Blackmore battles his brazen image  On a frigid Newcastle night last winter, a queue of Rainbow fans circled the stage door of the theatre where Ritchie Blackmore had just played to a full house. Blackmore had been thrilled with the fact that his entire British tour had sold out in two days, and was in a good mood over the favorable notices his band was getting.

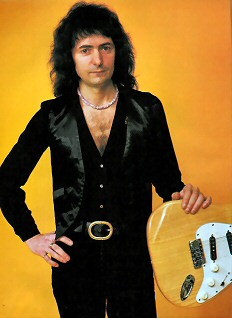

On a frigid Newcastle night last winter, a queue of Rainbow fans circled the stage door of the theatre where Ritchie Blackmore had just played to a full house. Blackmore had been thrilled with the fact that his entire British tour had sold out in two days, and was in a good mood over the favorable notices his band was getting.As Blackmore and the band (Don Airey, Roger Glover, Graham Bonnet and Cozy Powell) left the building, something happened that put a damper on Ritchie's enthusiasm. "A guy had stripped down to his underpants," remembers Airey, "in spite of the freezing cold. He bowed to Ritchie, saying, 'I've seen God! I've seen God!' I lost a leather jacket; it was torn right off my back, and I had to crawl out of the theatre." Such mishaps are the order of the day for a band whose average fan sports a denim jacket carrying the message "Blackmore is God." Rainbow's loud show, with its blinding flashes of light and smoky explosions, encourages the noisy responses of such believers. But the human object of all this idolatry - guitarist/songwriter Richard Blackmore - is as unlike the deity his fans worship as anyone you can imagine. Playing a genre of music dominated by Van Halens and Black Sabbaths, Blackmore is a renegade. He's a perfectionist, a musician who devises a dozen or more solos to a song before choosing the one he finally uses. He listens to classical organ and violin music for guitar ideas, but goes to the records of the other troupers on the metal machine circuit less often. At a Long Island rehearsal for his current tour, he executed a note-perfect Django Reinhardt number with his Stratocaster" that would have left Tony Iommi's thumb stuck in the strings. His answer to the popularity of Marvel Comics among the HM set is to read the prose thrillers of Dennis Wheatley, such as The Devil Rides Out or Uncharted Seas. But this is the private Blackmore, the side rarely glimpsed by hardcore fans of the deafening Deep Purple or the roisterous Rainbow. In spite of his stage flash, Ritchie is not a public person. "He takes it all very seriously," says keyboardist Airey, who used to play Chopin and Schumann before the hard rock bug bit him. "He looks at it as his profession. Rainbow is more musical than the average heavy metal group. It's just that when we try the more melodic numbers the crowd doesn't listen, so on stage it's always back to the headbanging."  Beneath the soft lights of New York's Warwick Bar, Ritchie Blackmore - 35, slim, dark-haired, hazel-eyed - sits and smiles. It's hard to gauge his height as he sips a Beck's beer at his table, but when he stands he's slightly above medium stature. His speech is articulate and without regional accent.

Beneath the soft lights of New York's Warwick Bar, Ritchie Blackmore - 35, slim, dark-haired, hazel-eyed - sits and smiles. It's hard to gauge his height as he sips a Beck's beer at his table, but when he stands he's slightly above medium stature. His speech is articulate and without regional accent.Despite the economic chance he may be taking playing huge arenas under the Rainbow banner (no Deep Purple reunion for him}, Blackmore is relaxed and talkative on the eve of his 53-city U.S. tour. He's not the moody egomaniac his detractors would have you believe. Ritchie isn't worried about the commerciality of his new Polydor LP, Difficult to Cure - his first with singer Joe Lynn Turner and drum recruit Bobby Rondinelli. Nor does he think his old reputation will get in the way of an upswing in his success that began with last year's British heavy metal revival. "I have the mean, moody image," Blackmore explains, "because I won't go out and talk to the 'right' people. I won't drop in at the 'right' radio stations. I don't like meeting Billboard's chief director backstage, and I don't go backstage at other people's shows. It was the glamorizing of rock & roll that made me leave Hollywood in '77. I know it sounds corny, but I like to play the guitar." Though Blackmore loves to perform heavy music, he doesn't listen to that much of it. "I like Jethro Tull, Ian Gillan, Jimi Hendrix, the Strawbs, Randy Hansen, Robin Trower, Bad Company, Led Zeppelin and Jack Bruce. Judas Priest? They have a good drummer." Ritchie doesn't care for Scorpions or Van Ballen. "Eddie Van Halen is excellent, technically, but he doesn't have the emotion that's supposed to go along the same lines as the vocal. I find the Who exceptionally average. But I listen to Bach all the time. I like his minor modes and his regimented way of arranging triplets. I love German Baroque organ music. All I do on the guitar is emulate a violin, which takes from sixteenth- and seventeenthcentury organ - which from a rock & roll viewpoint, I suppose, is horrible. But I really think melody in a solo is more important than technical dazzle." None of Blackmore's remarks sounds vicious or snobbish; his opinions are simply a reflection of his musical dedication and his Middlesex, England background. Born to a middle class family on April 14, 1945, Ritchie grew up in Heston and was originally destined to be an air traffic controller like his brother. But his grandmother, Edith Blackmore, played piano; she was always a subtle influence, and by the time Ritchie was 17, he knew rock guitar inside out, and found himself on the road in Europe with Gene Vincent. "Ritchie soon joined the Three Musketeers in Hamburg," recalls Don Airey. "They wore full musketeers' outfits, and leapt onstage with swords drawn before playing. Like Jimmy Page, Ritchie joined the Outlaws - they were a famous group then." By '64, Ritchie had signed on with Screaming Lord Sutch and the Savages, and befriended organist Matthew Fisher, who (like John Lennon) shared his fondness for Bach. Fisher later played on Rainbow's "Black Sheep of the Family." After a year off in Germany, where he met his first wife and fathered a son, Jurgen, Blackmore formed Deep Purple, whose first hit was "Hush" in 1968. The band had a #1 record, "Smoke on the Water," in the summer of 1973. Then strange things started to happen to Blackmore. "I found a girl in my garden once," he remembers. "I saw the bushes move, and a little head popped up. It was a French girl of eighteen who'd somehow followed me to England. I set the dogs on her," he says, deadpan. "They're friendly dogs; they just jumped into the bushes and she came out screaming. It was strange how she found my house. She went around touching the walls, caressing the house." Blackmore left England in 1975. Yet life hasn't been that different in Hollywood, Connecticut or Long Island, where Ritchie now lives (after two divorces) with his girl friend, Amy Rothman, and their cat, Raindrop. "People keep stealing deck chairs from outside the house," Blackmore says. "They want a collector's item. I have to keep buying deck chairs. I find it very strange." Blackmore rehearsed six hours a day for four and a half weeks before setting out on the "Cure" tour, which this month finds Rainbow in the Southeast, Midwest, Kentucky, Tennessee and Pennsylvania. That he keeps taking new band lineups out on his solo reputation is a sign of Blackmore's individualism. "Roger, Joe and I do write," says Don, but Ritchie is the main influence. I think he's taking a chance with his sales when he makes as many personnel changes as he does - the fans don't understand it - but he gives the group its direction." Hopefully, Blackmore's direction will work commercially in America for Difficult to Cure. "The heavier stuff on it," says manager Bruce Payne, "is in line with Deep Purple's Machine Head and Who Do We Think We Are?" At the same time, Joe Lynn Turner's husky, tuneful voice and Roger Glover's crafty production make some songs on the record sound like Free or Bad Company hits. "Polygram [the distributor] is dominated by Mercury Records promotion people right now, which, judging from the success of Rush and Def Leppard, is just what the doctor ordered for Rainbow," says Payne. But Blackmore claims he hasn't commercialized his music. "I don't like to try to sell myself. I hate fitting my music to the format of AM and FM stations. In rock & roll everybody plays with the same cliches now to try to get into the Top Ten. It's unproductive and it's boring, and the rebelliousness is gone. They might as well have Brooke Shields doing the FM DJ business; the sales technique is exactly the same as television jeans commercials. It's a brainwash. "Three hundred years ago, composers weren't writing for the Top Twenty. The music came from the heart of the musician. Maybe that's why I keep going back to that type of music. If a rock station is on, I like to hear my own songs; there's no point in writing them if they're not heard. But if I switch a radio on, I turn to a classical station. Thank God there were no FM stations in seventeenth-century Germany!" Black Magic Blackmore Richard Blackmore's fascination with the paranormal became most evident in the early days of Deep Purple. He'd already been intrugued by certain scary films, like the 1959 Hammer production of The Hound of the Baskervilles. Then someone in graphics or management - he's not sure which - added a "t" to Richie's name on the liner copy for Shades Of Deep Purple. "Fame,"he says lightly, "was thrust upon me." Numerologically, the extra letter made him a six instead of a nine, so Blackmore kept the "Ritchie" spelling. Soon he was exploring other strange phenomena. Circus: Is there any psychic reason for the high turnover of Rainbow musiscians? Blackmore: Maybe I was a vampire in an age gone by, 'cause I thrive on new blood and adrenalin - new people. I get very bored with people, which is probably my fault. Circus: Are you particularly interested in vampires?  Blackmore: I'm not a Dracula sort of person; movies vampires get tedious. I am interested in odd things that happen, especially ghosts. I'm not interested in extraterrestrial beings. Or Aleister Crowley, sacrificing little children and things like that. Tearing heads off chickens. Satanism - no. I just like ghost hunting. From the research I've done, I'm inclined to think there are ghosts.

Blackmore: I'm not a Dracula sort of person; movies vampires get tedious. I am interested in odd things that happen, especially ghosts. I'm not interested in extraterrestrial beings. Or Aleister Crowley, sacrificing little children and things like that. Tearing heads off chickens. Satanism - no. I just like ghost hunting. From the research I've done, I'm inclined to think there are ghosts.Circus: Do you like to work in a ghostly atmosphere? Blackmore: Yes, that's why I often take on castles when we rehearse and play. I don't like a modern environment. Circus: Is there a connection between Deep Purple and your interest in the supernatural? Blackmore: When we formed Purple, we had a bassist called Nic Simper. He used to do all these seances. I was totally opposed to all that, till I saw what was going on. I got intrigued with it all out of curiosity. I believe more in religion because I see what goes down in an evil sense. I don't practice evil stuff, but I see how effective it is. Circus: What are the ideal conditions for holding a seance? Blackmore: You can't be very tired. And you can't have weak personalities present; otherwise, you'll get possession. You need very strong, receptive personalities. Circus: What happens if a participant doesn't believe? Blackmore: A friend of mine, a guitarist, said, "Ah, I don't believe in all this rubbish. I'm not scared of you ghosts; I'm stronger than you are." The next moment, he was knocked out of his chair and was foaming at the moouth - he was unconcious. He had to go to a priest the next day, and the priest said, "Don't do that again; this is possession." You can go crazy if you're not carefull. A lot of people go too far, too soon. Mental hospitals are full of people who are actually possessed by troublemaking spirits. Circus: Do you meet "receptive" people when you tour? Blackmore: In this business I can come to meet a lot of people who have weird experiences. Usually it's a girl in the bedroom saying, "What weird experiences have you had?" I must meet a hundred "witches" a month. The real ones are very reluctant to come forward with their stories. You can tell when they're sincere. Unlike these people that push their way backstage with their tits hanging outgoing "I'm a with." © Richard Hogan, Circus 30 April 1981 |